Archive for the ‘earth spirituality’ Category

In the end we all do what we’re told. (It’s a backstage conversation.) We just differ on who we listen to, who we decide to heed. The cicadas from central casting announce August outside my window, under this overcast summer sky on a day of rain, and I sit grappling with this post. Somehow they’ll work their way in, because I listen to practically everything. Bards most of all, because they’re such electric company. Each cicada-Bard croons a Lunasa song, turning and tumbling toward the Equinox now, the days shortening at both ends, darkness nibbling at the warm hands of summer.

Do we really do what we’re told, and follow a script handed to us backstage? “No rehearsal. You’re on in 10 seconds.” Then Pow! Birth! And going off-script means following another script, the one titled rebel or train-wreck, fool or genius, or what have you. What do we have? “What is written is written,” runs the Eastern proverb about fate. “What can I say?” quips Buffy the Vampire Slayer. “I flunked the written.” So many scripts to choose, rehearse, try out. When we read for “human,” how many other lines do we forget? “I am a stag of seven tines,” sings Amergin, “I am a wide flood on a plain, I am a wind on the deep waters …” Memory and imagination, the same, or inversions of each other.

When poet Mary Oliver gives Bardic advice, “Instructions for living a life. Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it,” I want to shout “But attention and astonishment are both luxuries!” And they are: ultimate, essential luxuries. Yes, Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Writing teacher Robert McKee turns it around: “The unlived life isn’t worth examining.” Ouch! Take it personally like I do (though quickly I blunt the edge by applying it to characters I’ve written, all those understudies and stand-ins for my life) — take it personally and you may turn another way, determined perhaps this time to swallow life whole. This life is brand-new, never seen before. Old games, true, but new blood.

Backstage I overhear someone whispering, “Worry about living first, and if necessary, leave the examining to somebody else.” Is that meant for me? “You’re on! Break a leg!” Is that meant for me, too?

Broken. Stuckness. Does it happen more to people who overthink their lives, who need to see where each footstep will land before they take a step? Those who strive to word a version of their lives acceptable for a blogpost?

“When I am stuck in the perfection cog,” remarks author Anna Solomon,

–as in, I am rewriting a sentence a million times over even though I’m in a first draft or, I am freaking out and can’t move forward because I am not sure how everything is going to fit together—I find it helpful to tell myself: You will fail.

A soul after my own heart! Failure: our solid stepping stone to success. Because who IS sure how everything is going to fit together?

I have this written on a Post-it note. It might sound discouraging, but I find it very liberating. The idea is that no matter what I do, the draft is going to be flawed, so I might as well just have at it. I also like to look at pictures I’ve taken of all the many drafts that go into my books as they become books, which helps me remember that so much of what I am writing now will later change. When I am aware that my work is not as brave or true as it needs to be, I like to look at a particular photograph of myself as a child. I am about eight, sitting on a daybed in cut-off shorts, with a book next to me. I’m looking at the camera with great confidence, and an utter lack of self-consciousness. This photograph reminds me of who I am at my essence, and frees me up to write more like her. —Anna Solomon, author of Leaving Lucy Pear (Viking, 2016), in a Poets and Writers article:

No rehearsal — it’s all draft, to mix metaphors. And You will fail. But once you do the draft, paradoxically, it becomes rehearsal, revision. Re-seeing. We will look again in astonishment, memory or return, mirroring the same thing, and marvel differently. Our recognition when another tells the tale, when others speak for us because they can, they live here too, they see and speak our hearts’ truth. We know, partly, because of them. They’re versions of us, dying and being born together.

“When death comes,” Mary Oliver says in the poem of the same name,

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps his purse shut …

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

Oh, Mark Twain gathers himself to answer. I hold my breath. Maybe it’s both like and unlike anything you imagine. Can we fear only what we dimly remember? “I do not fear death,” Twain says. “I had been dead for billions and billions of years before I was born, and had not suffered the slightest inconvenience from it.”

Lunasa thoughts. The autumn in the bones and blood, while the young are dancing. Mead around the fire. We’re both grasshopper and ant in the old fable, gathering and spending it all so profligately. Expecting a pattern, a plan, we’re told to ignore the man behind the curtain. Sometimes there’s neither curtain nor man. Other times, both man and curtain, but as we approach, the spaces between each thread and cell, between each corpuscle and moment, each atom, have grown so large we can fly through appearances, into mystery, into daydream. Great Mystery drops us into the blossom before it’s open, we sip nectar, drowsing at the calyx, the Chalice. Mystery listens as the bees hum around us, gathering pollen. Stored up sweetness for the next season. To know itself, Mystery gazes from everything we meet, we see it in each others’ eyes, so it can see itself.

Attention, says Mary Oliver, attention is the beginning of devotion.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: Oscars.

“Growing where you’re not planted”

I’m feeling ornery. Walk with me a little?

Of course people aren’t “equal,” whether “created,” “evolved,” “born lucky,” “favored by the Fae” or anything else. We demonstrate this by almost every action we take, whatever we may say we believe. Whether it’s elections, classrooms, job reviews, dating, playing fields, friendships, family dynamics — the list goes on — one person’s clearly not equal to another. We have criteria, hopes and fears, standards, priorities, memories, expectations, goals, feelings, and values that we almost always take into account.

Even where we might expect equality to matter most, such as in matters of law, where we confuse equality with fairness or justice, we often argue our cases with claims of unique circumstances, histories, medical conditions and so on. We seek exceptions, work-arounds, concessions — because we feel fairness or justice requires it. The particulars and specifics of our lives and experience, talents and quirks and character, all those hallmarks of individual identity, really do matter.

But if we’re not “equal,” as I’m claiming here, what we all are is valuable, unique, and irreplaceable. Most versions of equality, far from helpfully “leveling the playing field,” begin by erasing the individual differences that define our unique value. Equality allows us to be lumped together in easily stereotyped groups. We become interchangeable, a homogenized mass. People start to generalize — “all ___ are ___ ” and when we do, we forget or ignore the value of individual identities. To consider just ethnic or racial terms, whether I’m “just another privileged white male” or “just another poor brown minority,” you can more easily write me off. I have no face, no personality, no distinct identity beyond my equality with everybody else in the category, the label pasted squarely on our foreheads. My unique birth, life and death don’t budge such pre-judgments, which is all that prejudice is, as long as they’re invisible.

[You know the story of the starfish? It’s made the rounds, but it still teaches. The version I’ve heard goes something like this: After a storm, one person encounters another on a beach. Driftwood and debris dot the sand, along with sea life stranded by the storm above the reach of the regular high tide. The second person is gently rescuing starfish and setting them back in the water. “Why bother?” asks the first person. “There are so many others that will die. You can’t save them all. How can it matter?” The other person pauses for a moment, with another wriggling starfish in hand, then sets it in the water. “It matters to this starfish.”]

So what does all this have to do with living on this green earth and loving it? Gardeners, for one, know firsthand: one patch of earth ain’t equal to another. Every location enjoys unique qualities of sun, wind, exposure, soil health, moisture, shade, nearby vegetation, bacteria, earthworms, insects, birds, animals and humans. Likewise for the seedlings, saplings, plantings, harvests, compost heaps, helpful and harmful beasts, bugs and spirits — none are merely “equal.” Or listen to that world just next door; the Morrigan is not Cernunnos. Brighid isn’t Kali. Christianity and Druidry aren’t “equally valid” — a meaningless assertion because of “equal,” not because of “valid.” Each helps catalyze a different life experience of the world. Both are needed. That’s why they’re here. But what good would they do if they were somehow “equal”? And what would that even mean?

The cosmos sweeps along, manifesting both equilibrium, often through relatively stable groups, and change, which appears frequently through the impact of individuals. It’s true that whole swaths of seemingly identical beings get tossed on the scrap heap all the time. A wildfire incinerates a mature forest, a flood washes away topsoil or drowns a lowland habitat. Severe frost or enduring drought destroys a whole ecosystem. Molds, rusts, viruses, spores and plagues decimate or erase innumerable species. Many more seeds and fingerlings, tadpoles and nestlings die than manage to survive. But let a first sapling rise in a meadow, and birds perch there, dropping new seeds that will change everything in a few years. The slightly altered DNA or behavior or adaptation of one or two individuals grants them increased advantages in a changed environment, and over time their line flourishes when others flounder.

Nothing is “equal.” In a cosmos both in love with and wholly indifferent to individuals, that is how we live at all — the ongoing surprise of the individual. Our uniqueness is our glory — and so is everyone and everything else’s. How to serve both these truths — not “equally” but lovingly — that’s a challenge you and I imperfectly explore all our days.

Some things glow with it,

flame-keepers, hearths we return to

whenever the world dulls and grays,

whenever bodies earth themselves

too deeply, those mornings each of us

can count all two hundred and six bones

stacked here in our skeleton houses.

Some things touch and smolder,

some kindle, flare once, no more.

Others spark and ignite everything around them.

Fire says: be done with cataloging. I

will renew. In the end, leave everything

for a bright journey. Burn

slow and long.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

New growth on the tips of our south boundary pines

[Thirty Days of Druidry 28]

“Should” is such a polarizing word. I write it here as a reminder most of all to myself. “Who are you to tell us what to do?!” Well, what difference does that make? If my suggestions are good, follow them. If they’re not, don’t. In the end, “who I am” really doesn’t matter much, does it? I’m not putting it out there as a distraction, so why let it be one for you? A road sign on a road you’re not travelling doesn’t apply to you, does it?

Besides, if my suggestions are good, you’re probably already practicing them in your own way.

(The next post will account for how well I follow my own advice.)

OK, here goes:

1–Druids should have a practice. I’m not saying what that is or should be, only that we each need one. Finding one we can stick with and make our own can be a deal of work. But without a practice, we lose focus, we fail to hear the hints — from others, from the green world, from dreams, from study and learning, from the nudge that comes in the shower or taking out the trash — that help keep us in balance. Otherwise, how are we more than armchair or coffee-table druids?

2–Druids should be able to talk about Druidry. Not proselytize. Not necessarily give interviews, record podcasts or lead workshops, unless that’s our thing. But if someone asks, a door is opening, and we can have an “elevator speech” ready. You know, an account of what we do, and how it makes a difference in our lives. One or two sentences can be enough. Otherwise, if we can’t manage that much, why are we doing what we do?

3–Druids should show their love of the earth. How we each do that is part of our own unique practice. Like all things, we have our birth and our bloom, our fruit and our fallow time. Otherwise, how do our lives build and contribute to this world we say we love?

4–Druids should keep learning. Neither we nor the world stands still, and much is stirring in many fields of learning that can enrich our practice, our knowledge, our awareness and our ability to work with the energies of the world for good. Otherwise, how else do we honor what we have been given?

5–Druids should respect their own needs. Our existences are such complex systems, and it becomes very difficult to fulfill the potential of our lives if pain, anger, illness, injury, or weakness overtakes us. It can be equally difficult to do more than we’re already doing if we have lives we live fully, without adding more than enough and driving us to a tipping point of imbalance. We should seek to know ourselves well enough to respect our own boundaries and limits, while asking which ones deserve to be there as supports, corner posts, roof-beams and garden fences, and which ones we can wisely transcend and grow beyond. Otherwise, how can we respect the same needs in others?

6–Druids should serve something greater than themselves. It may be a person, a spirit or god, a relationship, a practice, a community, a cause, an ideal, an institution, a way of life, a language — the possibilities are great. Otherwise, how do we give back and complete our half of the cycle?

7–Druids should listen more than they talk — and we talk a lot! By listening, we can hear music others miss, find beauty that others pass by, celebrate wonders that many children know but adults are coaxed to forget. Otherwise, how can we add our voices to the Great Song that sings each dawn, noon and sunset?

There’s my list. Anything you would delete, change, substitute? What “shoulds” do you follow on your own path?

If I ask what? then I’m alone in a world of things, none of which says anything to me, though I may listen as long as I like. After all, why ask a thing?! Trying too hard, I can almost believe I’m just another thing myself.

If I ask what? then I’m alone in a world of things, none of which says anything to me, though I may listen as long as I like. After all, why ask a thing?! Trying too hard, I can almost believe I’m just another thing myself.

But let me ask who? and then the world wakes to wonder. Atoms like me, earthed like me, kindred, sky-breathed like me this November afternoon. Yes, sparked like me, too, being here, in this place, now. Oh, let me lose no more songs that greet and open! You carry them, clouds — water too, and day gray on the hills.

/|\ /|\ /|\

If I ask who, this stone

whirling with its billion atoms

mostly empty space they say (though

touching it you’d never believe)

its presence, its jacket of moss

this stone talks, not loud

if anyone listens.

Talks to itself, hasn’t yet

heard hey! from anyone else

through a skin thick

against weatherdance and stormscrape

I believe a free hand

on its rough cool reaches,

I begin to learn its witness

slow offshear in wind and heat,

flake and shard and century chip.

Stone long alone will not yield soon

but with a palm against a sunside flank

you can feel it heed sun nonetheless

warming at the distant inquiry of light.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Who? is a song that wakes worlds. I wake you, you wake me, we rouse together singing.

The questions matter, though they’re one half of it. Mouth and ear, at the proportion of one to two, right for wisdom when the oak lets fall its hard fruit. Earth, you know. Who says so? A sapling, in a spring or two.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: moss rock.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

Bluets (houstonia caerulea) in our back yard

Bluets carpet our backyard lawn, an easy seduction into putting off the mowing I’ll need to do in another week. The air itself is a welcome. I no longer brace myself to step outside. Instead, I peel off an unnecessary extra layer and stand still, feeling my body sun itself in the coaxing warmth. Bumblebees chirm around the first blooms, goldfinches dart across the front yard, and our flock of five bluejay fledgelings from last year wintered over without a single loss and now sound a raucous reveille every morning.

In this last of a four-part series on Beltane, I want to look at our “found festivals” — how we also touch the sacred in the daily-ness of our lives. We don’t always have to go looking for it, as if it’s a reluctant correspondent or a standoffish acquaintance. When I attend to the season and listen to the planet around me, I touch the sacred without effort. The sacred encounter, like a handshake, is a two-part affair. How often do I extend my hand?

Susanne writes in a Druid Facebook group we both follow that finally in her northern location “the last bit of snow on the north side of the house melted away on Beltane day.” Gift of Beltane. Something to dance for.

Rudolf Steiner school celebration in Great Barrington, MA

The ritual calendar of much modern Paganism meshes with the often milder climate of Western Europe where it originated. It doesn’t always fit as well in the northern U.S. or Canada, or other places that have adopted it. (So we tweak calendars and rituals and observances. Like all sensible recipes say, “Season to taste.”)

It’s a cycle that the medieval British poet Geoffrey Chaucer celebrates in the Canterbury Tales by singing (I’m paraphrasing lightly):

the showers of April have pierced the droughts of March to the root … the West Wind has breathed into the new growth in every thicket and field … the small birds make their melodies and sleep all night with open eyes …

A Vermonter like me looks at Beltane looming on May 1 and reads those lines of Chaucer’s and thinks, “About a month too early, Geoffrey.” Spring, not summer, begins at Beltane, though to feel the recent temperatures on your face you might well think Beltane is the start of summer indeed. Game of Thrones fans, never fear: Winter will come (again). But now … ah, now … Spring!

Susanne continues:

and even though they are a symbol of Imbolc, the snowdrops are blooming merrily followed closely by the daffodils. The peepers are peeping, the owls are hooting, the woodcocks are rasping ‘peent’ on the ground and twittering in flight.

salamander crossing signs in our nearest town

Late April and early May here in southern VT, and in your home area, too, means an annual migration of some sort. Here it’s spotted salamanders. After dark, volunteers with flashlights man the gullies and wet spots to escort the salamanders safely across roads, and slow the chance passing car to the pace of life.

Beltane finds Susanne with her hands in the earth, responding to the call of Spring:

The weekend was spent with Spring clean up, turning the soil and sowing the greens and peas in the garden. I was a bit disappointed in myself that I haven’t held a Beltane ritual but then I realized that this was the ritual…working with the soil, plants and spirits of the land, listening to my favorite songs …

May you all touch the sacred where you are.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: bluets/houstonia caerulea — ADW; Great Barrington MA school celebration; salamander sign — ADW; yellow spotted salamander.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

In Part 1 I wrote about the approaching Festival of Beltane and our longing to touch or encounter the Sacred. It keeps calling to us, and will not be ignored.

Here I’ll talk about how we fulfill the call inside us to touch the Sacred.

Zora Neale Hurston, from her novel “Their Eyes Were Watching God”

One way to understand this call is as a sacred vow that our lives require each of us to fulfill. Being born means we agreed to it. Don’t remember making the vow? Each of us promised to make good on it. “Will you do what only you can do, because only you live your life? Will you listen to what there is for you to hear? Will you keep growing? Will you remember to celebrate all that can be celebrated?”

Our lives ask us such questions, and we answer with how we live. We honor the call, the sacred vow, when we’re fully alive. We catch intermittent glimpses of this in our lives. This joy is for you, it says.

Often we don’t trust it. A girl I was serious about before I met and married my wife was convinced we shouldn’t trust it. Every happiness has to be paid for with sorrow, she said.

Or we see it, this joy, in the lives of others. A light seems to shine around them, and in their presence you feel better, more balanced, more you. They seem to practice the sacred like a dance or song. That can be a powerful way to live. Life as practice. Not as a thing to be perfected. Life’s bigger than perfection, it seems to say. More ornery, stubborn, lovely and changeable.

But it’s something we can also study, perform, explore, try out, test, demonstrate, play with, give away and take back. Sometimes with each breath. Sometimes over nearly a century. Perfection’s a dead thing. Not alive, slippery, mysterious and intoxicating. Try out what lies on the other side of perfection. Not just play the hand I’m dealt, but take or drop a card. Reshuffle. Paint my own deck. And sometimes, change the game.

Right, says the skeptic. You just believe that if you want to. But ignore such hints and outright shoves, and likewise we can often feel both restless and spiritually dead, a truly wretched combination, when we’ve done less than our lives ask of us.

We all know this intimately, too, in one form or another. It prods young (and older) people to find themselves, it burns in those who are spiritual hungry to go on inner and outer quests that may take years or their entire lives, it launches many a mid-life crisis, a dark night or decade of the soul. It slaps you upside the head, and will not stop. It passes go, it drives up onto the sidewalk, it drops you off on the wrong side of town. Or it slows down, even stops, parks in a driveway, kills the engine, offers you the wheel — then tosses the keys into the bushes.

And the call troubles some people enough that they retreat into things in order to try to hush the call, to drown it out because they despair of ever being able to answer it. And the things — possessions, pleasures, addictions — being finite, can’t replace the call either. They just rub it raw. Who needs the sacred if it’s such torture?! No thanks, I say. These aren’t the droids I’m looking for.

Fortunately the sacred doesn’t just sit around waiting for us to find it like the fabled pot of gold at the rainbow’s end, like the toy in the bottom of the cereal box. It bounces and squirms and growls and seeks us out, constantly breaking through into our awareness. Hence the difficulty of avoiding the call, and the frequency with which we encounter it.

These Festivals like Beltane, or even newer observances, like Earth Day today — they don’t come out of nowhere. Sure they do, says your friendly neighborhood internet troll. OK: who ya gonna believe?

Where do we find the sacred — or where does it find us?

“Human Beauty”/Jano Stovka

We may touch the sacred when we experience beauty. And beauty not only meets us in familiar ways that marketers box and package and try to monetize, but also in less conventional ones, if we pay attention. And sometimes even when we don’t.

Experience beauty and we’re lifted out of ourselves, stopped in our tracks, slapped, arrested, pierced with Cupid’s arrow — the language we’ve used throughout history in poems and songs to describe the experience can sound violent, because we may not expect beauty, or recognize it when we face it, or want it when we do recognize it.

Or we do all of those things, and our hunger for it just grows and builds. Or it makes us weep or laugh, or act in other ways that don’t fit or which leave us uncomfortable. Wait, say our lives. You thought this was going to be easy or simple?!

Encounters with the sacred can come in isolation, too, of course — away from others. We may turn our backs on people who disappoint us or who are simply so loud in our lives that we need silence, or at least other sounds. Wind, crickets, birdsong, water. We set out by ourselves, convinced this is IT. This is the way.

Walk alone and some cultures, at some times, will understand and recognize and support you. They’ll assist the solitary walk in unique ways that other cultures may not be doing at that moment. Time, space, acceptance, easing the transition in or out.

Stairs at Oominesanji, Kii Mountains, Japan

No single culture does it all — culture’s a human thing as much as anything else is. But the natural world is a powerful ally — what we’re born from, where these bodies end up after a few decades. The in-between, where we convince ourselves we’re not a part but apart: the natural world offers remedies for that illness that we recognize every time we let it.

In Part 3 I’ll look at some more ways we touch the sacred.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: years that ask; addiction; Oominesanji Stairs; human beauty/Jano Stovka

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

Here we are, about two weeks out from Beltane/May Day — or Samhuinn if you live Down Under in the Southern Hemisphere. And with a Full Moon on May 3, there’s a excellent gathering of “earth events” to work with, if you choose. Thanks to the annual Edinburgh Fire Festival, we once again have Beltane-ish images of the fire energy of this ancient Festival marking the start of Summer.

You may find like I do that Festival energies of the “Great Eight”* kick in at about this range — half a month or so in advance. A nudge, a hint, a restlessness that eases, a tickle that subsides, or shifts toward knowing, with a glance at the calendar. Ah! Here we are again!

For me, that’s regardless of whether I’m involved in any public gathering, or anticipating the time — because it’s never anything as rigid as one single day, but rather an elastic interval — on my own.

Yes, purists may insist on specifics, and calculate their moons and Festivals down to the hour, so as not to miss the supposed peak energies of the time. And if this gives you a psychological boost to know and do this that’s worth the fuss, go for it.

Below is Midnightblueowl’s marvelous painted “Wheel of the Year” (with Beltane at approximately 9 o’clock). With its colors and images, it captures something of the feeling of the Year as we walk it — a human cycle older than religions and civilizations. Or the cycle helped make us human, changing us as we began to notice and acknowledge and celebrate it. Try looking at it both ways, and see what comes of that.

Painted “Wheel of the Year” by Midnightblueowl. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

/|\ /|\ /|\

For today I take as divination the message below, which got promptly diverted to the spam folder: “This page decidedly has whole of the information I precious astir this dependent and didn’t make love who to ask.”

O crazy spam-scribe of the ethers, you stumbled onto one of the Great Paradoxes, best stated by William Blake, with his “infinity in the palm of your hand, eternity in an hour.” In that sense, yes: this page “decidedly has whole of the information” though it is also what it is, a finite thing. Like each of us, like the tools we use to connect to What Matters, like the sneaking suspicion that will not go away that there’s Something More. (Even if it’s just an explanation of what’s up with all these capital letters, anyway?)

And since Beltane’s approaching, there is indeed a “precious astir” at work as the energies swirl. Who or what is “dependent”?! The writer of the spam, not knowing “who to ask” and even acknowledging he “didn’t make love.” And all of us, dependent on the earth and each other.

I bless you, oh Visitor to this e-shrine, workshop, journal — the many-selfed thing that blogs can be and become. Who to ask? you inquire. Your inward Guide, always present and waiting for you where you are most true. Or the face of the Guide as it manifests again and again in your life — stranger at the market who smiles at you, bird that catches your eye, tune you find yourself humming.

How to get there, that place we all long for, that colors our thinking and follows and leads us in day- and night-dreams? Place that Festivals and holidays and time and pain and love and living all — sometimes — remind us of? Ah, you mean The Question! Love, gratitude, service — all things any of us can begin today; all things, it’s important to remember, we already do in some measure, or we would die. Too easy? Or you already know that? There’s also ritual — finite, imperfect ritual, our human dance. Mark, O Spirit, and hear us now, confirming this our sacred vow …

What’s your sacred vow? Don’t know yet? Got some work to do? Tune in to the next post for more.

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: Beltane Edinburgh Fire Festival; painted Wheel of the Year by Midnightblueowl

*The “Great Eight” yearly festivals with their OBOD names: Imbolc, Alban Eilir/Spring Equinox, Bealteinne, Alban Hefin/Summer Solstice, Lughnasadh, Alban Elfed/Autumn Equinox, Samhuinn, Alban Arthan/Winter Solstice. Many alternate names exist, and almost every one has a Christian festival on or near it, too.

Earlier today my wife and I walked through the brilliant winter sunlight on the neighborhood loop that took us past snowfields already blue with late afternoon shadows.

Looking southeast around 3:30 pm

I’ve quoted the Philip Larkin poem “First Sight” before, but today it seemed perfect as a tribute to the goddess whose hearth (or in our case, woodstove) I worship at particularly intensely on these frigid midwinter days.

Imbolc as guide: more than half our wood remains.

Spring will come, and as goddess of fire and smithing, Brighid warms and heals and shapes us. Lack of any promising evidence for that change bothers her not at all.

Larkin’s poem means more to us, because just four miles from our house a local farmer milks his herd of some 90 sheep and sells a variety of sweet, rich cheeses in a little shed halfway down the lane to his milk barn. Lambing season is usually later than February in the Northeast, for the simple reason that it’s too cold for the newborns in anything other than a heated shelter. Push the ewes to conceive too early in the fall, and you’ll end up with dead lambs. Larkin captures this time of change in a somewhat milder climate, but still snowy. Memory had me reciting his lines again to myself as we walked. I had to come back and locate the poem to fill in the gaps I couldn’t bring to mind:

Lambs that learn to walk in snow

When their bleating clouds the air

Meet a vast unwelcome, know

Nothing but a sunless glare.

Newly stumbling to and fro

All they find, outside the fold,

Is a wretched width of cold.

As they wait beside the ewe,

Her fleeces wetly caked, there lies

Hidden round them, waiting too,

Earth’s immeasureable surprise.

They could not grasp it if they knew,

What so soon will wake and grow

Utterly unlike the snow.

This always moves me — a transfomation we simply cannot see coming merely by looking around us. No evidence here, at least none we can make out. Even, sometimes, a “vast unwelcome.” Life in this world is catalyst. It never leaves us alone. What gifts of the gods and spirits and our own ancestors will wake and grow in us? Will we let ourselves be surprised? Brighid, may it always be so!

/|\ /|\ /|\

The rangy willow in our backyard has been feeling the sun these past several days. Even with its branches garbed in snow, you can make just make out in the crown of the tree the first faint reddish-green hint of spring in the depths of this February cold. Imbolc upon us. “They could not grasp it if they knew,/What so soon will wake and grow.” Memory of other Februaries wakes and hints at what will return, against the odds.

Backyard willow

With the triplet of Imbolc, Groundhog Day (in the U.S.), and a full moon tonight on Feb 3, it seemed right to celebrate today and tonight, the third day of the three. And this evening my wife and I enjoyed homemade potato soup rich with leeks and garlic and sour cream — we practiced the traditional Italian “mangiare in bianco” — literally, “to eat in white” in observance of the moon, without also “eating blandly or lightly,” as the expression can indicate, too.

The hill to our east, cresting perhaps four hundred yards above our roof, delays sunrise and moonrise both. Moonrise tonight “officially” hit Brattleboro VT at 5:09 pm. We wait for it longer here.

At first I thought the image below was a discard. A tree-trunk obscures one edge of the moon, and the horizon is hazy. But then I saw it perfectly captured our Imbolc experience. Slowly the sky cleared as the temperature continued to drop towards 0 (-18 C), as it has the last several nights. Hunger Moon* rose higher, and the moon-shadow of a pine in the backyard leaned out dark against the snow in the moonlight. I took another shot.

Moon around 6:45 pm, shortly after clearing our hilltop

Praise to Brighid and life and light, warmth human and divine in our veins, in the animals and plants around us! May our vision of the Whole become clear as the moon this night.

Moon around 8:00 pm

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Hunger Moon” is one of the Native American names for February — and never fails to make me shiver.

Image: Snow lamb.

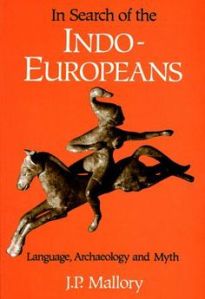

I’ve mentioned my obsession with Indo-European (IE) in previous posts, and given samples of a conlang I derived from IE and use in ritual. One of the many fascinations of this reconstructed language that’s the ancestral tongue of 3 billion people — half the people on the planet alive today — is the glimpses into the culture we can reconstruct along with the language. (Here’s a visual of the IE “family” and many of its members.) How, you thoughtfully ask, can we really know anything about a culture dating from some 6000 years ago – the very approximate time period when the speakers of the IE proto-language flourished? A good question — I’m glad you asked! – and one hotly contested by some with agendas to push – usually a nationalist or religious agenda intent on serving a worldview that excludes some group, worldview or idea. Hey kids, let’s define our club du jour by those we don’t let in!

I’ve mentioned my obsession with Indo-European (IE) in previous posts, and given samples of a conlang I derived from IE and use in ritual. One of the many fascinations of this reconstructed language that’s the ancestral tongue of 3 billion people — half the people on the planet alive today — is the glimpses into the culture we can reconstruct along with the language. (Here’s a visual of the IE “family” and many of its members.) How, you thoughtfully ask, can we really know anything about a culture dating from some 6000 years ago – the very approximate time period when the speakers of the IE proto-language flourished? A good question — I’m glad you asked! – and one hotly contested by some with agendas to push – usually a nationalist or religious agenda intent on serving a worldview that excludes some group, worldview or idea. Hey kids, let’s define our club du jour by those we don’t let in!

But the most reasonable and also plausible answer to the question of IE language and culture is also simpler and less theatrical. Indo-European is the best and most thoroughly reconstructed proto-language on the planet — and it’s true there’s much still to learn. But after over two hundred years of steady increases in knowledge about human origins and of thoroughly debated and patient linguistic reconstruction, the techniques have been endlessly proven to work. And if a series of words that converge on a cultural point or practice can be reconstructed for IE, then the cultural practice or form itself is also pretty likely. Notice I don’t say merely a single word. Yes, to give a modest example, IE has the reconstructed word *snoighwos “snow” (the * indicates a reconstruction from surviving descendants — see footnote 1 below for a sample) – and that possibly suggests a region for an IE “homeland” that is temperate enough to get snow. After all, why have a word for a thing that’s not part of your world in any way? But wait — there’s more!

Here’s an uncontested (note 2) series of reconstructions – *pater, *mater, *sunu, *dukter, *bhrater and *swesor – all pointing to an immediate family unit roughly similar to our “nuclear family,” with father, mother, son, daughter, brother and sister all in place. It’s fairly safe on the basis of this cluster of reconstructed words – and others, if you still doubt, can be provided in painfully elaborate detail – that with a high degree of probability, an IE family existed all those millennia ago that would also be recognizable in modern times and terms.

[Side note: almost every reconstructed IE word listed in this post has a descendant alive in modern English. Want proof? Post a comment and I’ll be happy to provide a list!]

Things understandably get touchier and more contentious when we move on to words and ideas like *deiwos “god”; *nmrtya “immortality”; *dapnos “potlatch, ritual gift-exchange”; *dyeu + *pater “chief of the gods” (and Latin Jupiter); *sepelyo– “perform the burial rites for a corpse”; and a few whole phrases like *wekwom tekson, literally “weaver of words, poet” and *pa- wiro-peku, part of a prayer meaning something like “protect people and cattle.”

Things understandably get touchier and more contentious when we move on to words and ideas like *deiwos “god”; *nmrtya “immortality”; *dapnos “potlatch, ritual gift-exchange”; *dyeu + *pater “chief of the gods” (and Latin Jupiter); *sepelyo– “perform the burial rites for a corpse”; and a few whole phrases like *wekwom tekson, literally “weaver of words, poet” and *pa- wiro-peku, part of a prayer meaning something like “protect people and cattle.”

What else can we conclude with considerable confidence about the IE peoples? Many lived in small economic-political units governed by a *reg– “king, chieftain” and lived in *dom– “houses.” Women *guna, *esor left their families at marriage and moved to live with their husbands *potis, *ner, *snubhos. A good name *nomen mattered then just as it does today – even with social media both exalting and trashing names with sometimes dizzying speed – though small-town gossip always filled and fills that role quite well, too. Heroes dominated the tales people told round household and ceremonial fires *pur, *ogni in the village *woikos, *koimos at night *nokwti. The most powerful and famous *klewes– heroes succeeded in slaying the serpent or monster of chaos: *oghwim eghwent “he slew the serpent” and thereby earned *klewos ndhghwitom “undying fame” (note 3). Special rites called for an *asa altar and offerings *spond-, because the universe was a place of an ongoing re-balancing of forces where the cosmic harmony *rti, *rta needed human effort to continue.

With Thanksgiving in the wings, it’s a good time for reflection (is it ever not?). Ways of being human have not changed as much as we might think or fear or be led to believe. Family, relationships, good food and drink, a home, meaningful work, self-respect – these still form the core of the good life that remains our ideal, though its surface forms and fashions will continue to shift, ebb and flow. Hand round the *potlom cup and the *dholis, the portion each person shares with others, so that all may live, and we can still do as our ancestors did: give thanks *gwrat– and praise for the gift *donom of life *gwita.

/|\ /|\ /|\

1. Linguistic reconstruction involves comparing forms in existing and recorded languages to see whether they’re related. When you gather words that have a strong family resemblance and also share similar or related meanings, they help with reconstructing the ancestral word that stands behind them, like an old oil portrait of great-great-great grandma in the hallway. Some descendant or other probably still walks around with her characteristic nose or brow or eyes, even if other details have shifted with time, marriage — or cosmetic surgery.

For *snoighwos, a sample of the evidence includes English snow, Russian snegu, Latin nix, niv-, Sanskrit sneha-, and so on. The more numerous the survivals in daughter languages, the more confident the reconstruction usually is. After a while you see that fairly consistent patterns of vowels and consonants begin to repeat from word to word and language to language, and help predict the form a new reconstruction could take.

A handful of reconstructed words have descendants in all twelve (depending on who does the counting) of the main IE family groups like Italic (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, all the Romance languages, and others), Celtic (Irish, Welsh, Breton, Manx, etc.), Germanic (German, English, Dutch, Icelandic, Norwegian, Frisian, Swedish, Gothic, etc.), Baltic (Latvian, Lithuanian, Prussian), Slavic (Russian, Serbian, Polish, Czech, Ukrainian, Slovene, Polabian, Old Church Slavonic, etc.), Greek (Doric, Macedonian, Attic, etc.), Tocharian (A and B), and Indo-Iranian (Sanskrit, Pali, Avestan, Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, Sindhi, Kashmiri, Dari, Pashto, Farsi, Baluchi, Gujerati, etc.) and so on, to name roughly half of the families, but nowhere near all the members, which number well over 100, not counting dialects and other variants.

2. “Uncontested” means that words with approximately these forms and meanings are agreed on by the overwhelming majority of scholars. If you dip into Indo-European linguistics journals and textbooks, you’ll often see algebraic-looking reconstructions that include details I exclude here — ones having to do with showing laryngeals, stress, vowel length and quality, etc. indicated by diacritics, superscripts and subscripts.

3. Even without the details mentioned in note 2 above, some reconstructions can still look formidably unpronounceable: I challenge any linguist to give three consecutive oral renderings of the second element in the reconstructed phrase *klewos ndhghwitom! The point to remember is that these are usually cautious reconstructions. They generally “show what we know.” Vowels tend to be much more slippery and fickle than consonants in most languages, and so they’re also less often completely clear for IE than the consonantal skeleton is. Several people, me among them, have worked on versions of “Indo-European for daily use”!

Images: Mallory; Indiana Jones the linguist.

Corrected 18 Dec. 2014

It’s almost here: Halloween, All Hallows Eve, Samhain/Samhuinn, Dia del los Muertos, Day of the Dead. Whatever you call it, it’s one of the most unusual festivals in the calendar. In this post I want to take a different tack, exploring history at least somewhat removed from the usual Christian-Pagan fireworks that continue to pop off annually around this time. Because the Druid-pleasing answer* to “Is it Christian?” and “Is it Pagan?” is “Yes.” What matters more, I hope, is what that can mean for us today.

A recent (Tues., Oct 28) issue of the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper features an article on Halloween by British historian Ronald Hutton, who’s well known in Druid circles both for the quality and thorough documentation of his historical work and also his interest in Druidry. Among many other points, Hutton addresses the impression, widespread in Great Britain, that Halloween’s an import from the U.S. It’s not, of course, being instead as English as Monty Python and Earl Grey (and later, as Irish as the Famine, and Bailey’s Irish Cream). Hutton’s observations suggest a connection I’d like to make in this post, in keeping with this time of year. Hence my title, which will become clear in a moment. Just bear with me as I set the stage.

November, rather unimaginatively named “Ninth Month” (Latin novem), was called in Anglo-Saxon Blodmonath, the “blood month” — not for any “evil, nasty and occult” reasons beloved of today’s rabble-rousers, but for the simple fact this was the month for the slaughter of animals and preservation of meat for the coming season of darkness and cold.

Hutton observes that the ancestor to modern Halloween:

… was one of the greatest religious festivals of the ancient northern pagan year, and the obvious question is what rites were celebrated then.

The answer to that is that we have virtually no idea, because northern European pagans were illiterate, and no record remains of their ceremonies. The Anglo-Saxon name for the feast comes down to an agricultural reality, the need to slaughter the surplus livestock at this time and salt down their meat, because they could not be fed through the winter. A Christian monk, Bede, commented that the animals were dedicated to the gods when they were killed, but he did not appear to know how (and they would still have been eaten by people).

Hutton proceeds to examine how we can nevertheless reconstruct something of that time and its practices through careful research. As a Janus-faced holiday, Halloween marked the fullness and completion of the harvest and return home of warriors and travelers — a time to celebrate. It also marked the coming of the hardest season — winter: cold, dark, often miserable and hungry, and sometimes fatal. People then measured their ages not in years but in winters — how many you’d survived. Hutton eloquently conveys all this — do read his article if you have time.

And because so much of North America bears the imprint of English culture, I want to peer at one particular autumn, and the Hallowed Evening that year, in England 948 years ago. It’s 1066, a good year at the outset, as historian David Howarth paints it** in his wonderfully readable 1066: The Year of the Conquest. A year, strangely enough, both like and unlike our own experience so many generations later in 2014:

It was not a bad life to be English when the year began: it was the kind of life that many modern people vainly envy. For the most part, it was lived in little villages, and it was almost completely self-sufficient and self-supporting; the only things most villages had to buy or barter were salt and iron. Of course it was a life of endless labour, as any simple life must be, but the labour was rewarded: there was plenty to eat and drink, and plenty of space, and plenty of virgin land for ambitious people to clear and cultivate. And of course the life had sudden alarms and dangers, as human life has had in every age, but they were less frequent than they had ever been: old men remembered the ravages of marauding armies, but for two generations the land had been at peace. Peace had made it prosperous; taxes had been reduced; people had a chance to be a little richer than their forefathers. Even the weather was improving. For a long time, England had been wetter and colder than it normally is, but it was entering a phase which lasted two centuries when the summers were unusually warm and sunny and the winters mild. Crops flourished, and men and cattle throve. Most of the English were still very poor, but most of the comforts they lacked were things they had never heard of.

Howarth’s account continues, vivid in detail; he chooses the small town of Little Horstede near Hastings that dates from Saxon times for his focus, to examine the immediate and later impact of the Norman Conquest.

Harold in the Bayeux tapesty, with a hawk

By early autumn of the year, things still looked promising for the English. True, their king Harold Godwinson, new to the throne just that past January, faced a dispute with the Norman duke William over the succession after the late king Edward passed. But Harold was Edward’s brother-in-law, he apparently had the late king’s deathbed promise of the throne, he was unanimously elected by the Witan (the English council of royal advisers), and he was a crowned and fully invested king as far as the English were concerned.

He was also proving to be a competent leader and warrior. When an invading army of some 7000*** Norwegians under Harald Hardrada and Harold’s exiled brother Tostig landed in the Northeast of England, Harold rode north in force, covering the 180 miles between London and Yorkshire in just four days, meeting and defeating the Norwegians on September 25 in the Battle of Stamfordbridge. The peace that the English had enjoyed was tested, but as word spread of this English victory, you can imagine the relief and the sense that all might well continue as it had for decades now. The rich harvest of 1066 went forward, and plans could proceed for the annual All Hallows celebration.

Swithun (d. 862), bishop, later saint, of Winchester

England was by this time thoroughly Christian (see St. Swithun, left), though folk memories of older practices doubtless persisted, mixed with a fair helping of legend and fantasy and uneven religious instruction from the local priests. The Christian retrofitting of Pagan holidays, holy sites and practices is well documented, and hardly unique to Christianity — the same thing occurs worldwide as religions encounter each other and strive for dominance or co-exist to varying degrees. To name just a few examples, take for instance Roman polytheism and many faiths in the lands of the ancient Empire, with Roman priests adding one more deity statue to the crowd for each new god they encountered, including the current emperor of course (with most peoples acquiescing happily except for those odd Jewish monotheists and their bizarre prohibition against such images!); Buddhism and the emergence of the Bon faith in Tibet; Shinto and Buddhism in Japan; and mutual influence between Islam, Sufism, and older practices like the Yazidi faith in the Middle East.

In his Guardian article on Halloween, Hutton notes:

All Saints Day, Oswiecim, Poland

It is commonly asserted that the feast was the pagan festival of the dead. In reality feasts to commemorate the dead, where they can be found in ancient Europe, were celebrated by both pagans and early Christians, between March and May, as part of a spring cleaning to close off grieving and go forth into the new summer. On the other hand, the medieval Catholic church did gradually institute a mighty festival of the dead at this time of year, designating 1 November as the feast of All Saints or All Hallows, initially in honour of the early Christian martyrs, and 2 November as All Souls, on which people could pray for their dead friends and relatives. This was associated with the new doctrine of purgatory, by which most people went not straight to hell or heaven but a place of suffering between, where their sins were purged to fit them for heaven. It was also believed that the prayers of the living could lighten and shorten their trials, as could the intercession of saints (which is why it was good to have all of those at hand). The two new Christian feasts were, however, only developed between the ninth and the twelfth centuries, and started in Germanic not Celtic lands.

Yet all was not peace in England. The triumph that was the Battle of Stamfordbridge proved short-lived. Disturbing rumors kept arriving of William assembling an army of invasion across the English Channel on the shores of Normandy, in fact ever since January when Harold received the crown. The English king began preparations for defense. Yet as the days and months passed, and the good weather for such crossings steadily diminished as all of September and then early October came and went without incident, most people began to relax. England would enjoy a breathing space for this winter at least. Whatever might happen next spring, this late in the year no one chanced the storms, fog and rough water, least of all a large army that would have to arrive by boat.

Yet William and his invasion force did just that. After weeks of bad weather, the wind finally shifted to favor the Norman leader, and he and his men set sail on September 27. When word came to the English king of the Norman landing, with ships and troops on the southern shore of England, king Harold and company rode back south, already weary from one major battle, right into another.

Yet William and his invasion force did just that. After weeks of bad weather, the wind finally shifted to favor the Norman leader, and he and his men set sail on September 27. When word came to the English king of the Norman landing, with ships and troops on the southern shore of England, king Harold and company rode back south, already weary from one major battle, right into another.

Careful excavation, study of contemporary accounts, and site visits mean that resources like the Eyewitness to History website can give us a portrait like this:

Harold rushed his army south and planted his battle standards atop a knoll some five miles from Hastings. During the early morning of the next day, October 14, Harold’s army watched as a long column of Norman warriors marched to the base of the hill and formed a battle line. Separated by a few hundred yards, the lines of the two armies traded taunts and insults. At a signal, the Norman archers took their position at the front of the line. The English at the top of the hill responded by raising their shields above their heads forming a shield-wall to protect them from the rain of arrows. The battle was joined.

Contemporary accounts record how the two armies fought all day, until Harold was dispatched with an arrow through one eye. Shortly after that, the disabled king was cut down by Norman warriors, and England’s fate turned.

Years later the Bayeux Tapestry commemorated a version of the event. But of course at the time there was no Twitter feed, no broadcast of news minutes after it happened by correspondents on the scene. No Fox News and CNN to digest and sort through the implications according to the politics of the day. Word of the battle and what it might mean would take weeks to spread, rippling northward from the coast where the first battles took place. For much of England, the Hallowed Evening, the All Saints Day of 1066 came and went without change.

At this distance, and without knowing the details, most of us may naturally have the impression Hastings was decisive. King Harold dead, battle won, QED. From there, we assume, William advanced toward London, accepted the grudging fealty of a defeated people, and after maybe quelling a few sparks of resistance or rebellion, took firm control of the throne and nation and ruled for the next 21 years, until his death in 1087.

Except not. True, William was crowned king in Westminster on Christmas Day 1066. But the following years brought their own troubles for the Norman king. Here’s the Wikipedia version (accessed 10/30/14; endnotes deleted):

Despite the submission of the English nobles, resistance continued for several years. William left control of England in the hands of his half-brother Odo and one of his closest supporters, William FitzOsbern. In 1067 rebels in Kent launched an unsuccessful attack on Dover Castle in combination with Eustace II of Boulogne. The Shropshire landowner Eadric the Wild, in alliance with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd and Powys, raised a revolt in western Mercia, fighting Norman forces based in Hereford. These events forced William to return to England at the end of 1067. In 1068 William besieged rebels in Exeter, including Harold’s mother Gytha, and after suffering heavy losses managed to negotiate the town’s surrender. In May, William’s wife Matilda was crowned queen at Westminster, an important symbol of William’s growing international stature. Later in the year Edwin and Morcar raised a revolt in Mercia with Welsh assistance, while Gospatric, the newly appointed Earl of Northumbria, led a rising in Northumbria, which had not yet been occupied by the Normans. These rebellions rapidly collapsed as William moved against them, building castles and installing garrisons as he had already done in the south. Edwin and Morcar again submitted, while Gospatric fled to Scotland, as did Edgar the Ætheling and his family, who may have been involved in these revolts. Meanwhile Harold’s sons, who had taken refuge in Ireland, raided Somerset, Devon and Cornwall from the sea.

Pacification, oddly enough, usually involves violence.

Ideologies and politics trouble us this Halloween just as they did 948 years ago, on a misty green island off the continent of western Europe.

Centuries later, as blended Norman and English cultures formed a new unity, the Protestant Reformation which swept much of Great Britain blotted out the doctrine of purgatory and the practice of prayer for saintly intercession. But as Hutton notes, Halloween “survived in its old form in Ireland, both as the Catholic feast of saints and souls and a great seasonal festival, and massive Irish emigration to America in the 19th century took it over there.”

In fact, having made this a citation-heavy post anyway, I’ll give Hutton nearly the last word, which is also his last word in his article:

In the 20th century [Halloween] developed into a national festivity for Americans, retaining the old custom of dressing up to mock powers of dark, cold and death, and a transforming one by which poor people went door to door to beg for food for a feast of their own, morphing again into the children’s one of trick or treat. By the 1980s this was causing some American evangelical Christians to condemn the festival as a glorification of the powers of evil (thus missing all its historical associations), and both the celebrations and condemnations have spilled over to Britain.

On the whole, though, the ancient feast of Winter’s Eve has regained its ancient character, as a dual time of fun and festivity, and of confrontation of the fears and discomforts inherent in life, and embodied especially in northern latitudes by the season of cold and dark.

There’s a worthwhile Conquest. “Is it Pagan?” “Is it Christian?” Let’s ask “Is it holy?”

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: jack-o-lanterns; Harold on the tapestry; St. Swithun; battle map; All Saints Day, Oswiecim, Poland, 1984.

*Rather than dualities and polar opposites, ternaries and triples permeate Druidry. As J. M. Greer observes,

Can anything as useful be done with the three elements of Iolo’s Druid philosophy, or for that matter with the four medieval or five Chinese elements?

Nwyfre, gwyar, and calas make poor guides to physics or chemistry, to be sure. Their usefulness lies elsewhere. Like other traditional elemental systems, the three Druid elements make sense of patterns throughout the universe of our experience. Tools for thinking, their power lies in their ability to point the mind toward insights and sidestep common mistakes.

Take the habit, almost universal nowadays, of thinking about the universe purely in terms of physical matter and energy. This works fairly well when applied in certain limited fields, but it works very badly when applied to human beings and other living things. Time and again, well-intentioned experts using the best tools science has to offer have tried to tackle problems outside the laboratory and failed abjectly. Rational architecture and urban planning, scientific agriculture and forestry, and innovative schemes for education and social reform often cause many more problems than they solve, and fail to yield the results predicted by theory.

Why? The theoreticians thought only of gwyar and calas, the elements of change and stability, expressed here as energy and matter. They left something out of the equation: nwyfre, the subtle element of life, feeling, and awareness. They forgot that any change they made would cause living things to respond creatively with unpredictable changes of their own.

In every situation, all three elements need to be taken into account. They can be used almost as a checklist. What is the thing you’re considering, what does it do, and what does it mean? What will stay the same, what will change, and what will respond to the change with changes of its own? This sort of thinking is one of the secrets of the Druid elements.

**Howarth, David. 1066: The Year of the Conquest. Penguin Books, 1981, pgs. 11-12.

***A conservative figure — estimates range as high as 9000.

Not responsible for spontaneous descent of Awen or manifestation of the Goddess. Unavailable for use by forces not acting in the best interests of life. Emboldened for battle against the succubi of self-doubt, the demons of despair, the phantoms of failure. Ripe for awakening to possibilities unforeseen, situations energizing and people empowering.

Not responsible for spontaneous descent of Awen or manifestation of the Goddess. Unavailable for use by forces not acting in the best interests of life. Emboldened for battle against the succubi of self-doubt, the demons of despair, the phantoms of failure. Ripe for awakening to possibilities unforeseen, situations energizing and people empowering.

Catapulted into a kick-ass cosmos, marked for missions of soul-satisfying solutions, grown in gratitude, aimed towards awe, mellowed in the mead of marvels. Optimized for joy, upgraded to delight, enhanced for happiness. Witness to the Sidhe shining, the gods gathering, the Old Ways widening to welcome.

Primed for passionate engagement, armed for awe-spreading, synchronized for ceremonies of sky-kissed celebration. Weaned on wonder, nourished by the numinous, fashioned for fabulousness. Polished for Spirit’s purposes, dedicated to divine deliciousness, washed in the waters of the West, energized in Eastern airs, earthed in North’s left hand, fired in South’s right. Head in the heavens, heart with the holy, feet in flowers, gift of the Goddess, hands at work with humanity. Camped among the captives of love, stirred to wisdom in starlight, favored with a seat among the Fae, born for beauty, robed in the world’s rejoicing, a voice in the vastness of days.

Primed for passionate engagement, armed for awe-spreading, synchronized for ceremonies of sky-kissed celebration. Weaned on wonder, nourished by the numinous, fashioned for fabulousness. Polished for Spirit’s purposes, dedicated to divine deliciousness, washed in the waters of the West, energized in Eastern airs, earthed in North’s left hand, fired in South’s right. Head in the heavens, heart with the holy, feet in flowers, gift of the Goddess, hands at work with humanity. Camped among the captives of love, stirred to wisdom in starlight, favored with a seat among the Fae, born for beauty, robed in the world’s rejoicing, a voice in the vastness of days.

Knowing, seeing, sensing, being all this, you can never hear the same way again these two words together: “only human”!

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: three from a sequence taken yesterday, 3 Oct 14, on a blessed autumn day in southern Vermont two miles from my house.

I’ll return to A Druid Way (and the fourth post in the “American Shinto” series) when I get back from the annual East Coast Gathering (ECG) this coming weekend. This year’s 5th ECG shares in some of the energy of the OBOD 50th anniversary earlier this summer in Glastonbury, UK. For many U.S. Druids, the Gathering is the principal festival event of the year, a chance to renew old friendships, enter sacred time and space, and reaffirm ties to the special landscape of Camp Netimus in NE Pennsylvania. This year’s Gathering theme is “Connecting with the Goddess.”

In the interim, here are three images from last year’s Gathering — a visual invocation of the Alban Elfed/Autumnal Equinox energies of the Camp.

Camp Netimus sign — photo courtesy Krista Carter

Steps up to fire circle from Main Lodge — photo courtesy of Wanda GhostPeeker

The evening bonfire

[Related posts: Shinto & Shrine Druidry 1 | 2 | 3 || Shinto — Way of the Gods || Renewing the Shrine 1 | 2 || My Shinto 1 | 2 ]

Below are images from our recent visit to Spirit in Nature in Ripton, VT, some eight miles southeast of Middlebury as the crow flies. An overcast sky that day helped keep temperature in the very comfortable low 70s F (low 20s C). At the entrance, Spirit in Nature takes donations on the honor system. The website also welcomes regular supporters.

As an interfaith venture, Spirit in Nature offers an example of what I’ve been calling Shrine Druidry, one that allows — encourages — everyone into their own experience. Everyone who chooses to enter the site starts out along a single shared path.

The labyrinth helps engage the visitor in something common to many traditions worldwide: the meditative walk. The labyrinth imposes no verbal doctrine, only the gentle restraint of its own non-linear shape on our pace, direction and attention.

Beyond the labyrinth, a fire circle offers ritual and meeting space. Here again, no doctrine gets imposed. Instead, opportunity for encounter and experience. Even a solitary and meditative visitor can perceive the spirit of past fires and gatherings, or light and tend one to fulfill a present purpose.

Beyond the circle, the paths begin to diverge — color-coded on tree-trunks at eye-level — helpful in New England winters, when snow would soon blanket any ground-level trail markers. When we visited, in addition to the existing paths of 10 traditions, Native American and Druid paths branched off the main way, too new to be included on printed visitor trail maps, but welcome indicators that Spirit in Nature fills a growing need, and is growing with it.

The Druid Prayer captures a frequent experience of the earth-centered way: with attention on stillness and peace, our human interior and exterior worlds meet in nature.

The trails we walked were well-maintained — the apparently light hand that brings these trails out of the landscape belies the many hours of volunteer effort at clearing and maintenance, and constructing bridges and benches.

A bench, like a fire pit and a labyrinth, encourages a pause, a shift in consciousness, a change, a dip into meditation — spiritual opportunities, all of them. But none of them laid on the visitor as any sort of obligation. And as we walk the trail, even if I don’t embrace the offered pause, the chance itself suggests thoughts and images as I pass that the silence enlarges. I sit on that bench even as I walk past; I cross the bridge inwardly, even if it spans a trail I don’t take.

Sometimes a sign presents choices worthy of Yogi Berra’s “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

Perhaps it’s fitting to close with the North, direction of earth, stone, embodiment, manifestation — all qualities matching the interfaith vision of this place.

/|\ /|\ /|\

This is the 200th post at A Druid Way. Thanks, everyone, for reading!

[Related posts: Shinto & Shrine Druidry 1 | 2 | 3 || Shinto — Way of the Gods || Renewing the Shrine 1 | 2 || My Shinto 1 | 2 ]

The continuing interest among visitors here at A Druid Way in the posts on Shinto says hunger for the Wild, for spiritual connection to wilderness and its rejuvenating spirit, and potentially for Shrine Druidry, remains unabated. No surprise — in our hunger we’ll turn almost anywhere. What forms our response to such hunger may take is up to us and our spiritual descendants. Spirit, the goddesses and gods, the kami, the Collective Unconscious, Those Who Watch, your preferred designation here _____, just might have something to say about it as well.

What we know right now is that we long for spirit, however we forget or deny it, papering it over with things, with addictions and with despair in this time of many large challenges — a hunger more alive and insistent than ever. And this is a good thing, a vital and necessary one. In an artificial world that seems increasingly to consist of hyped hollowness, we stalk and thirst for the real, for the healing energies the natural world provides all humans as a birthright, as participants in its “spiritual economy” of birth, growth, death and rebirth.

As physical beings we live in a world where breathing itself can be a spiritual practice, where our heartbeats sound out rhythms we are born into, yet often and strangely have tried to flee. Even this, my sadness and loss, can be prayer, if I listen and let them reach and teach me, if I walk with them toward something larger, yet native to blood and bone, leaf and seed, sun and moon and stars. Druidry, of course, is simply one way among many to begin.

/|\ /|\ /|\

If you know Kipling‘s Just So stories, you’re familiar with “The Cat That Walked By Himself.” The cat in question consistently asserts, “All places are alike to me.” But for people that’s usually NOT true. Places differ in ease of access, interest, health, natural beauty, atmosphere — or, in convenient shorthand, spirit. Shrines acknowledge this, even or especially if the shrine is simply a place identified as Place, without any sacred buildings like Shinto has — a place celebrated, honored, visited as a destination of pilgrimage, as a refuge from the profane, as a portal of inspiration.

Here’s a local (to me) example of a place in Vermont I’ll be visiting soon and reporting on, one that sounds like an excellent direction for a Shrine Druidry of the kind people are already starting to imagine and create. It’s called Spirit in Nature, and it’s a multi-faith series of meditation trails with meditation prompts. Its mission statement gets to the heart of the matter:

Spirit in Nature is a place of interconnecting paths where people of diverse spiritual traditions may walk, worship, meet, meditate, and promote education and action toward better stewardship of this sacred Earth.

Spirit in Nature is a non-profit, 501 (c)3 tax-exempt organization, always seeking new members, local volunteers to build and maintain paths, financial contributions, and interest from groups who would like to start a path center in their own area.

/|\ /|\ /|\

So much lies within the possible scope of Shrine Druidry it’s hard to know where to start. Many such sites (and more potential sites) already exist in various forms. Across Europe, and to a lesser degree in North America (public sites, that is: private Native American and Pagan sites exist in surprising numbers), are numerous sacred-historical sites (some of which I’ll examine in a coming post), often focusing around a well, cave, tree, waterfall, stone circle, garden, grove, etc. Already these are places of pilgrimage for many reasons: they serve as the loci of national and cultural heritage and historical research, as commemorative sites, spiritual landmarks, orientations in space and time, as treasures of ethnic identity — the list goes on. Quite simply, we need such places.

Lower Falls, Letchworth St. Pk, NY. Image by Wikipedia/Suandsoe.

The national park system of the U.S., touted as “America’s Best Idea” (also the title of filmmaker Ken Burns’ series), was established to preserve many such places, though without any explicit markers pointing to spiritual practice. But then of course we already instinctively go to parks for healing and restoration, only under the guise of “vacations” and “recreation.” And many state parks in the U.S. extend the national park goal of preserving public access to comparatively unspoiled natural refuges. Growing up, I lived a twenty-minute bike ride from Letchworth State Park in western NY: 14,000 acres of forest surrounding deep (in places, over 500 feet) gorges descending to the Genesee River. Its blessing follows me each time I remember it, or see an image of it, and in attitudes shaped there decades ago now. May we all know green cathedrals.

I’ll talk more about shrines on other scales, small and large, soon, and tackle more directly some of the similarities and differences between Shinto and Druidry. I’ll also look at some of the roles practitioners of earth-centered spiritualities can — and already do — play in connection to the creation and support of shrines.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: spider web; Lower Falls at Letchworth State Park, New York.