Archive for the ‘awen’ Category

[Part One]

This post on creating a usable Celtic ritual language continues a number of previous posts on the subject.

Why do such a thing — create a new Celtic ritual language, rather than master an existing Celtic tongue, when all of them struggle to survive and need all the support they can get? Better yet, why not instead devote the same energy and time to creating rituals, songs, poems, prayers in the language of everyone who will take part? In a word, why be obscure?

Because language is — or can be — magical. Because sometimes we need the power of audible speech that means something only to us. Because a ritual language, a holy tongue, carries its own potency, apart from matters of practicality. Because a dedicated language, like anything else, accrues value and energy and strength precisely because it’s been set apart, treated with care and esteem, as a thing worthy of respect. Because if you go to the trouble of creating a ritual language, I assert that you honor the gods just as much as you do by learning an existing one. Because there’s a world of difference between theft and inspired imitation.* Because a vow, a dream, a burst of awen guided you to do so.

Here’s the prayer that opened the post linked to above:

For the gift of speech already, I thank you.

For the gift of a Celtic tongue I will make,

let my request be also my gift to you in return:

the sound of awen in another tongue, kindred

to those you once heard from ancestors

of spirit. Wisdom in words, wrought for ready use.

May your inspiration guide heart and hand,

mind and mouth, spirit and speech.

/|\ /|\ /|\

So in the face of loud and rude reasons not to, you follow the urging to create a ritual language anyway. The Celtic world tugs at you, your practice draws on Celtic imagery, myth and folklore, and you opt for a Celtic language over a (re)constructed tongue native to the land where you live. (The possibilities of a Native American conlang deserve a separate post.)

Resources abound for such a project. After all, we have six surviving Celtic languages — Breton, Cornish, Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh. We have reconstructed Proto-Celtic, we’ve got inscriptions in other extinct Celtic languages, and we have a couple of centuries of linguistic analysis that helps to clarify grammar, word derivations, pronunciation, etc. Beyond that are several Celtic conlangs of varying degrees of realism and fidelity to the historical Celtic languages (like Arvorec, Brithenig, Caledonag, Galathach, Proto-Brittonic, etc.).

In addition to language proper, we’ve got scripts, too, like Ogham and the Coelbren alphabet. An embarrassment of riches, truly.

Coelbren alphabet

/|\ /|\ /|\

So where to begin?

I’m partial to P-Celtic, or Brythonic (Breton-Cornish-Welsh), so that’s my starting point, rather than Q-Celtic or Goidelic (Irish-Manx-Scots Gaelic). But take your pick. It’s your flavor of awen, after all.

We can assemble a basic word-list of a few hundred items pretty quickly. In an hour, you’ll have enough for simple phrases even as you continue to tinker. For help, Omniglot has gathered some useful comparative lists to launch you, and so has this Wikipedia comparative table. (Mostly it’s the vowels that may need tweaking, but that can wait until later.) So we’ll start here with a small sample:

den: man [dehn]

dor: door [dohr]

gwreg: woman [roughly goo-REG]

plant: child [plahnt]

ti: house [tee]

ci: dog [kee]

mab: son [mahb]

tir: land [teer]

mam: mother [mahm]

mor: large [mohr]

neweth: new [NEH-weth]

bihan: small [BEE-hahn]

drug: bad [droog]

gweled: see [GWEH-led]

bod: be [bohd]

Every word above has clear cognates (“relatives”) in Welsh, Breton and Cornish, so we’re on very solid ground so far. Aim for a consistent pronunciation, write it down so you remember, devise a simple key as in the brackets above, and you’re on the way.

We know Brythonic, like Goidelic, had a definite article, for which we’ll choose an. So we can say “the man, the woman”, etc.: an den, an gwreg.

(We can address how we might want to handle those infamous Celtic sound changes later. To give just one a quick example, feminine nouns historically change their initial sound after the definite article, so we might include a rule that gives us gwreg, an wreg; mam, an vam, etc.)

We know that Celtic adjectives typically follow the noun they modify, as in the Romance languages:

an tir mor: the large land

ti neweth: new house

mab bihan: small son

ci drug: bad dog

We know that Brythonic, like the Celtic languages generally, makes phrases equivalent to English “the door of the house, the child of the land” by juxtaposing the words: dor an ti, mab an tir. (Again, we can work out any sound changes later.)

In addition, we know that Celtic often favors a verb-first sentence order (a simplification, but a useful starting point), as if in English we said “Sees the man the dog” instead of “The man sees the dog.”

So we can construct simple sentences:

Bod an gwreg an tir. The woman is the land.

Gweled an mab an ti mor. The son sees the large house.

Now this should serve to show the beginnings of what’s possible without earning a graduate degree in Celtic Studies. If you’re creating solely for yourself, you can follow the promptings of your guides, ancestors and awen. A dream, a book, a contemplation or a museum visit may inspire a particular project: a prayer, a chant or song, a rhyme or invocation, a simple story.

If you’re creating for or with a group, other factors may arise. How complex do you need the grammar? What kinds of things do you want or need to say? How regular and intuitive should the pronunciation be? Are others working directly with you in expanding the vocabulary, or are they asking you as their tribal bard for original and translated rituals and prayers in the language?

For instance, Celtic has an invariable relative pronoun, given here as “a”, which lets us make sentences like this:

Bod hi an gwreg a gweled an tir neweth. She is the woman who sees the new land.

Your choices as you create, after awen, the gods and common sense each have their say, operate in a cauldron that balances flexibility, regularity, variety and ease of use. Like any recipe, season to taste.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: Coelbren alphabet;

*A note on cultural appropriation — as John Beckett suggests in his The Path of Paganism, “always credit your sources, never pretend to be something you’re not, and steal from the best”. To put it another way, all cultures borrow from each other, or die.

Where do I go from here?

All right — I’ll admit the title-as-opaque-acronym is at least a little clickbaity. (I do like the “dig” in the middle of it — it fits one of the themes for this post.)

But more importantly, this is the question I find my life keeps asking, in ways both small and large. What next?

Large: like many cancer survivors, I monitor numbers from regular blood tests. The slow rise I’ve seen over the past 5 years in undesirable antigens means I can’t grow complacent. “Leave nothing on the table,” counsels an elder I know who’s grappling with dementia. A life lived within limits isn’t a disaster: from everything I’ve seen, it’s the only way life happens. Nobody “does it all”. (The young adult novel I’ve got one-third finished won’t get completed on its own. It’s up, and down, to me.)

Small: a Meetup group I’ve been nurturing patiently is finally large enough to gather for an Equinox/Ostara potluck. A member’s offered her home, and we’ve got several people committed to bringing a dish to pass. One more chance to practice savoring the shoots and leaves of new growth that spring makes its specialty.

In-between: unable to afford to buy a bigger house (we opted 9 years ago for small), or encouraged by any leads to move out of state for jobs, my wife and I focused on asking how to flourish where we are. She eventually found part-time work, and we built an addition to give us breathing room. I’m getting good writing ideas faster than I can get them on paper or screen.

How to survive, yes, of course. But how to thrive, the deeper quest.

Sometimes the big picture isn’t what I need, though I thought it was. Sometimes, instead, it’s just the next step, it’s the phone call I remembered to make this afternoon, it’s the contemplation or ritual tomorrow morning. It’s the short walk that reveals sudden green beneath melting snow. It’s the porcelain hare my aunt gave me 50 years ago.

Sometimes the big picture isn’t what I need, though I thought it was. Sometimes, instead, it’s just the next step, it’s the phone call I remembered to make this afternoon, it’s the contemplation or ritual tomorrow morning. It’s the short walk that reveals sudden green beneath melting snow. It’s the porcelain hare my aunt gave me 50 years ago.

I think “half a century” and don’t know what I feel. Then I think “half a century” again, and I say to myself, “I’m still here, still wondering what comes next”. I take the delicate figure down from the shelf and blow from its pink and white ears the dust from a season of wood stove ash. The picture’s not quite in focus, but my camera doesn’t do closeups any better. A piece of wisdom: it doesn’t have to be perfect.

And I open for the 100th time the demanding draft of a workshop I’ll be giving at Gulf Coast Gathering on “30 Days and Ways to Tap the Awen”.

Well, I remind myself, you asked for them. The inward sap bucket fills, after a winter’s dry season. Now the trick of a moment (a life): to open my heart wide enough to receive.

“Each mortal thing does one thing and the same”, sings Gerald Manley Hopkins, that wonderful bard who observed his world so loving-wisely. You can read the poem I’m reflecting on here at this site, which includes a bite-sized biography, along with short, helpful observations.

“One thing and the same”, Hopkins says, sounding confident, like he really knows.

What? you ask. The thing we all are, a self that “[d]eals out that being indoors each one dwells”: the “indoors” we each inhabit, the self we look out from onto everything around us. Deal it out, pay it out like divination, rope or money or time.

Hopkins gets it. He goes on: “Selves – goes itself, myself it speaks and spells”. Each self does this, it goes as itself, it “selves”, as if we are all verbs now, and everything we do speaks us and conjures us both out of and into the cosmos. To live at all is a magical act, “to be alive twice” as another poet calls it. From time to time we hear the echo of both lives, the two halves of us we can’t ignore, that kindle in us a human restlessness we can never extinguish. It’s also what we are, what we do as selves.

I’m born and I come upon myself, I gradually become self-aware, the self simply a larger and more engaging preoccupation among all the other things I do. Each of us sits in a self like we sit on benches. The bench of the self weathers in place, this place, the world of heights and depths, times and places.

And what is the “speech” and “spell” it utters? Bard-like, Hopkins says it like he hears it: all these selves “Crying What I do is me: for that I came“.

I’m doing it right now, and it also will take me my entire life to do it completely. When my heart stops and my last breath goes out, I’ll have finished this particular doing, one turn on the spiral, whether I become the lichen near the bench or the shadow of tree-trunks or a tree or a human again, or something else “different”, says Whitman in another poem, bard singing to bard and to all of us, “different from what any one supposed, and luckier”.

Have you felt it, luck in the sunlight, possibility on your skin? There’s Druid-luck just in living, which I can know if I heed the reminders, or ignore them and suffer. Either way, it hurts, says therapist Rollo May. I’ll suffer anyway. OK, on to do something through and around and even, if I have to, with my suffering. What I do is me: for that I came.

“Don’t you know yet?” scolds Rilke. (Damn these bards! The conversation hasn’t stopped since awen first stirred in us. One thing and the same. We recognize it in others, in the voice of the Bards, because we’re doing it too.

What? I ask again. Rilke answers, part of the Song singing all of us here, the voice at the center of things that makes music out of us all, the voice we hear in dreams and silence and sound, laughter and tears and the spaces inside us.

Fling the emptiness out of your arms into the spaces we breathe;

perhaps the birds will feel the expanded air with more passionate flying.

…..

Of course, it is strange to inhabit the earth no longer,

to give up customs one barely had time to learn,

not to see roses and other promising Things in terms of a human future;

no longer to be what one was in infinitely anxious hands;

to leave even one’s own first name behind, forgetting it as easily as a child abandons a broken toy.

Strange to no longer desire one’s desires.

Strange to see meanings that clung together once, floating away in every direction.

And being dead is hard work and full of retrieval before one can gradually feel a trace of eternity.

Retrieval. Of course we fear death, if we’ve done it so many times before. A healthy fear of death, something I know, rather than terror of what I don’t know. I’ve done this death thing countless times already. What’s one more?

Well, a great deal. How many years to retrieve this time around, to begin to recall things I’ve never forgotten, maybe, but misplaced, thrown out, ripped up and shredded even, for decades, centuries. A self that emerges out of nothing, returns to it, and also manages a retrieval, with the help of crazy bards and singers on the edges, reminding us. Pointing us back to song that’s still singing us, notes on the wind.

What I do is me: for that I came.

/|\ /|\ /|\

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

Solstice light, blessings and inspiration to you all! And to everyone Down Under at the official start of winter, may the Light grow within and without!

With this post I finally complete the “Thirty Days of Druidry” series I began back in April. And ever as one cycle ends, another begins. We enter the dark half of the year with the greatest light and energy, a lesson in itself that things are never wholly as they appear, that each thing bears its apparent opposite in its bosom, as the Dao De Jing gently urges us to realize.

With this post I finally complete the “Thirty Days of Druidry” series I began back in April. And ever as one cycle ends, another begins. We enter the dark half of the year with the greatest light and energy, a lesson in itself that things are never wholly as they appear, that each thing bears its apparent opposite in its bosom, as the Dao De Jing gently urges us to realize.

Beyond the binary surface of the polarities all around us lie multitudes of other relationships to explore. Water offers itself as a teacher: we’re either above or below the surface. But what about right at the face of the water? There we encounter surface tension, the point of contact, where air and water meet and the silver mirror may open in either direction to allow us entry. Or dancing. Water striders live at the boundary and let it support and sustain them. Air and water together allow for dancing as well as power. What other such natural meetings may we attend?

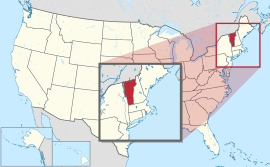

Texas Falls, Hancock, Addison County, Vermont

Here in Vermont in the NE part of the U.S., summer moved in weeks ago, with days in the high 80s and low 90s (27-31 C), and blessed nights in the 50s and 60s (13-17 C), perfect for sleeping. With open windows, birds wake us between 4:30 and 5:00 am, sometimes, it seems, just because they can. They’re out and about, so why shouldn’t the rest of the world be? Or in the middle of the night, the pair of owls that nest nearby rouse us with hunting calls under a moon full last night.

Here in Vermont in the NE part of the U.S., summer moved in weeks ago, with days in the high 80s and low 90s (27-31 C), and blessed nights in the 50s and 60s (13-17 C), perfect for sleeping. With open windows, birds wake us between 4:30 and 5:00 am, sometimes, it seems, just because they can. They’re out and about, so why shouldn’t the rest of the world be? Or in the middle of the night, the pair of owls that nest nearby rouse us with hunting calls under a moon full last night.

Sometimes life consists of what you can sleep through, and what grabs you drowsing and drags you back to consciousness. War, pestilence, earthquake, songbirds, rain on a standing-seam roof, gentle breathing of your bed-mate. De-crescendo. Wake, or sleep on?

The chimney sweep came this last Friday to brush and vacuum. Even with filters and professional care, for an hour after he left, a trace of ash and soot perfumed the air indoors. And we await delivery next week of the three cords of wood that will see us through to next summer. Bars of gold, sunlight stacked in tree-form. Solstice days.

/|\ /|\ /|\

I ask for divination. Over the last weeks the nudge has come to build a small Druid circle in our back yard. It’s another liminal place. Leave it unmowed, and blackthorn and milkweed eagerly launch a takeover. Not sunny enough for a garden, though it gets about two hours of light mid-morning. But here, by 11:50 am at midsummer, it’s already mostly in shade. Here’s the space, looking north, our small pond to the left beyond the uncut grass.

The first divination came a few days past, as I was finishing mowing. A box turtle animated by the day’s heat, crawling north across our yard. As quick as I was to grab my camera, here it is at the treeline. Unhappy with my attempts to stage it in order to get a better picture, it’s nosed its way under leaves. A foot-long paint-stick lies next to it, to give a sense of scale.

What does it “mean”? Divination benefits from context, and I’m going for three readings, a small but proven sampling of the currents of awen afoot.

Stay tuned.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: Texas Falls; Vermont;

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

Rhododendron in bloom in our front yard, loud with bees

Since I laid out “Seven Shoulds” for Druids in the previous post, it’s only fair that I should account for how, and how well, I myself manage to do them. Here goes …

1–”Druids should have a practice.”

Ha! I laugh ruefully, because I follow two paths. Sometimes that seems double the challenge. Who needs it? I sometimes think.

But I find that if each day I can manage a practice from even one path, it “spills over” to the other path. They link — a topic for a whole book, I’m beginning to suspect.

I “get credit” on both paths, to put it crassly. Yes, practicing for “credit” means I’m pretty much scraping the bottom of the awen (inspiration) barrel, but sometimes ya gotta go with what you get. Not every day is Lucas Industrial Light and Magic. (If it was, I’d fry and blow away.)

Having a practice also means keeping the ball rolling, the flame burning, even and especially when you don’t feel like it. Then the gift comes, luck turns things around, chance plays things our way, and a god or two peers at me directly for a moment. Because of our efforts? Not always directly, like calculating a sum in math. The universe is more than a spreadsheet. But without the practice, it’s funny how whatever luck and chance and grace and gift I experience will begin to dwindle, dissipate and drain away.

The Galilean Teacher observed, “Those who have will be given more, and those who have little will lose the little they have.” At first encounter, this piece of gnomic wisdom sounded to me like some kind of nightmare economics. Punish the poor, reward the 1%, and all that. But when I look at it as an insight about gratitude — a practice all its own — it starts making a lot more sense. Unless we make room, there’s no space left in us for more. We have to give away to receive. It’s neither more blessed to receive or to give. Both are necessary for the cycle to operate at all.

If I blog or compose verse or do ritual, if I chant or contemplate or visualize, if I love one thing freely without reservation or thought of what’s in it for me, I’ve reached out to shake hands with Spirit. I find that “energy hand” is always held out to us, but unless I offer my half of the handshake and complete the circuit, nothing happens. “What’s the sound of one hand clapping?” goes the Zen koan. More often for me it’s “What’s the greeting of one hand offered?” Pure potential, till I do my part.

2–”Druids should be able to talk about Druidry.”

If inspiration fails, I fall back on John Michael Greer’s fine lines to prompt me into my own “elevator speech”: “Druidry means following a spiritual path rooted in the green Earth. It means embracing an experiential approach to religious questions, one that abandons rigid belief systems in favor of inner development and individual contact with the realms of nature and spirit” (1).

Of course, trot that out verbatim in reply to most casual inquiries, and you’ll probably shut people down rather than open up a conversation. I’m a book addict myself, but I don’t need to talk like one.

So here’s a more conversational version. “For me, Druidry means walking a spiritual path that’s based in the earth’s own rhythms. I try to take an experiential approach to questions big and small. That means I value inner growth and personal contact with nature and spirit.” I find something like that offers plenty of handles if anyone wants something to grab onto. It also has the Druidic virtue of consisting of three sentences.

3–”Druids should show their love of the earth.”

Sometimes this can be more far reaching than just what we ourselves do. Our choices reach more widely than that. Who we interact with also has consequences. We had a builder in recently to rescue our garage, which for every one of the eight years we’ve lived here has been sliding another half-inch down the slope of our back yard.

It took us a fair while to find him. Referrals and ads and word-of-mouth turned up people we eventually chose not to work with. But this fellow was different. Just one proof among several: his attention to reseeding the lawn and cleaning up construction waste after he’d completed the repairs helped us show our love of the earth through our choices of our interactions with others. We didn’t see or know this fully until after the fact, of course. But it was confirmation — the sign we needed. Some days it’s all we get to urge us to keep on keeping on.

I chose this example rather than any other because it was subtle in coming, though just as important as recycling or using less or any of the other things we try to do to “live lightly.” Druidry need not always “speak aloud” to have effects and consequences. Ripples spread outward, hit the far shore, and return. “What you do comes back to you.”

4–”Druids should keep learning.”

Many Druids made this a habit long ago. They have another book or five ready when they’re done with the current one. That’s me. It’s a competition, I’ve come to believe, who will win, my wife or me. She’s a weaver and has baskets and boxes of thread, heddles, wrenches, loom-parts, table-looms, tapestry manuals, and two car-sized looms, all striving for space with my shelves of language books, histories, Druidry and magic texts, boxes of novel and poem drafts, newspaper clippings, letters, and more.

But as J M Greer notes, “Druidry isn’t primarily an intellectual path.” Thank goodness! I’m saved from the limits of intellect, however well I’ve trained and domesticated it! Greer continues: “Its core is experiential and best reached through the practice of nature awareness, seasonal celebration, and meditation” (2).

Druids find themselves encountering people to learn from, the aging carpenter or herbalist or gardener who’d love for an apprentice willing to put in the hard work. So then we happen along and appreciate them and “apprentice for a moment” if not a decade. They’re often self-educated, regardless of what level of school they’ve completed. They seek out people to learn from, and recognize and honor the same impulse in others. Druidry, among all the other things it is, proves itself a wisdom path.

Companion rhododendron in rose, always blooming a week later

5–”Druids should respect their own needs.”

Oh! This is sometimes so large it’s like the air we breathe all our lives, easy to forget. Rather than scold ourselves for lapses, failings and limitations, celebrate what we have done. “More than before” is a goal I take as a mantra. Even two steps backwards gains me some insight, however painfully won, if I look and listen for it. And it gains me compassion for myself and others in our humanness– no small thing. As a Wise One once remarked, who would you rather have around you, someone right or someone loving?

Some six years out from cancer surgery and radiation treatment and I still don’t have the energy I once did. I’m also that much older. But I can rage against and mourn new physical limits, or I can find work-arounds for what I need to do, and set clearer priorities for what really matters, so as not to squander what I do have. Sure, it’s still a work in progress. But I find I can detect small-minded attitudes and deep-seated prejudices in myself more quickly, and do the daily work of limiting their influence and filling their space with more positive thoughts and actions. That’s a gain.

Ever danced your anger? All emotions are energy responses. But I don’t need to sit and stew in them. I can use them to propel myself to new places and spaces and states. It’s an older-person magic, perhaps, or maybe just one I’ve been a long time in realizing and appreciating and practicing.

6–”Druids should serve something greater than themselves.”

Looking back at the list I included — “a person, a spirit or god, a relationship, a practice, a community, a cause, an ideal, an institution, a way of life, a language” — I realize I’ve served all of ’em at some point. Some people stick with one their whole lives. It becomes their practice.

Right now, underemployed as I like to say, I’m more of a homebody than I’ve been, and consequently around the house more. If I find myself sparked to annoyance or anger at my wife for some petty thing, as can happen in the best of relationships, I try to remember to serve her, to serve the relationship. Again, can I use my anger, rather than just seethe? Can I remember to bless my anger, transform its energy and spend it to uncover an underlying issue? What’s the pattern I’ve been feeding? Do I want or need to keep feeding it? Serve myself in this way, in the deepest sense, and I serve others, and vice versa. No difference. To paraphrase, all things work together for good for those who love something that lifts them out of smallness and limitation.

7–”Druids should listen more than they talk — and we talk a lot!”

I’ve certainly demonstrated that here in this post, to say nothing of this whole blog.

Fortunately, one of my go-to practices is listening. Do I do it enough? Wrong question. “Some — any — is more than before.” Both paths I follow commend practices focused on sound as a steady daily method of re-tuning, so that Spirit can reach me through every barrier I may erect against it. Chanting awen, listening to music that opens me, finding literal in-spiration — ways to breathe in what is needed in the moment — letting the song roll through me and back out to others in quiet daily interactions — these are the practices I keep returning to. Listen for the music, whispers my life.

The Great Song keeps singing, blessedly, through my intermittent disregard and obliviousness, till I remember to listen again, and join in.

/|\ /|\ /|\

- Greer, John Michael. The Druidry Handbook, qtd. in Carr-Gomm, Philip. What Do Druids Believe? London: Granta Books, 2006, p. 34.

- Greer, The Druidry Handbook., p. 4.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

[Some days, about all I can muster is a good gray awen.]

[Gray, grey. “If it’s good enough for Gandalf, then it’s good enough for me.”]

[Gra/ey magic(k). 1) a hair coloring product. 2a) Magic not performed for specifically beneficial purposes. 2b) (derogatory) Magic which avoids annoying ethical considerations. 2c) Magic practiced to confuse, mislead or perplex others. Roy Bowers’ version (link to article): “your opponent should never be allowed to confirm an opinion about you but should always remain undecided. This gives you a greater power over him, because the undecided is always the weaker.”]

/|\ /|\ /|\

“Light is the left hand of Darkness.”

Finally the Chief of the Urdd Awen Ddu rose and called for silence with a curious circular gesture. He was a slim, short man who nevertheless had a commanding presence. His simple black robe accentuated his dark eyes. Power spoke in his voice.

“Opposition strengthens us, like a good resistance training exercise. Contrary to the fears of our opponents, it’s not our intention to ‘cover all the lands in a second darkness.’ Our opponents grow stronger as well. But we have a secret they do not know.”

Almost no shadow

He paused to scan the room and gather eyes. “In the darkness we cast almost no shadow at all. With this energy freed, this psychic weight lifted, we may work our will with advantage. We read in the Hebrew scriptures how even God says, ‘I will give you the treasures of darkness and the hoards in secret places.’* And we have learned together how to recognize and gather these treasures that those who work in light never see, nor ever know. They cannot, not as long as they resist polarity, or think to vanquish one half of the universe.”

A good speaker weaves enchantment over an audience, and the Chief did so now. “Others may fear the Dark. But we have learned, my brothers and sisters, to know and respect its nature and its extent. Identifying with it, its reach becomes our own, and from the concealment darkness offers, we may extend our grasp to life in a way that light cannot. Anciently the Wise have declared, ‘Light is the left hand of Dark.’ Once prepared, as we have prepared ourselves, we can welcome it and grow from it — from the Dark.”

A good speaker weaves enchantment over an audience, and the Chief did so now. “Others may fear the Dark. But we have learned, my brothers and sisters, to know and respect its nature and its extent. Identifying with it, its reach becomes our own, and from the concealment darkness offers, we may extend our grasp to life in a way that light cannot. Anciently the Wise have declared, ‘Light is the left hand of Dark.’ Once prepared, as we have prepared ourselves, we can welcome it and grow from it — from the Dark.”

/|\ /|\ /|\

“Moreover it doth not yet appear that these arts are fables: for unless there were such indeed, and by them many wonderful and hurtful things done, there would not be such strict divine, and human laws made concerning them …” (Henry Cornelius Agrippa, Three Books of Occult Philosophy. First published 1531. This edition translated by James Freake, edited and annotated by Donald Tyson, Llewellyn Publications, St. Paul MN, 8th printing, 2005).

Of course, this and the previous two posts on the hypothetical Order of the Black Awen are hardly the last word to be said on the subject, nor infallibly workable truths about either the Dark or the Light such as the unwary might conclude, but they are nonetheless one entry, one doorway, one path in themselves.

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Isaiah 45:3.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

“Well, Druid, you need to work on manifesting your intention. Lots of missing posts in your ‘Thirty Days of Druidry.'”

“I know. I’m doing the best I can. Really. Remember what it is that ‘happens when you’re making other plans’? Got some of that going on. Hey, look at that bird over there!”

I’m finding that occasionally setting an intention publicly, however modest it is, is good training. In my universe, the secret to success is to keep failing until I don’t anymore. They’re inevitable, really, both the failure and the eventual not-failing. And I find that remarkably comforting. All I have to do is to ‘keep on keeping on.’ I can even ‘give up,’ until I weary of that, too, and I start again. Of course failure is always an option — I’ve come to know this intimately. Don’t we all? Otherwise, what would success even mean?

/|\ /|\ /|\

One of the listeners who had joined us a short while ago around the fire now spoke up. A small silver brooch on her robe at the left shoulder caught the firelight and flashed briefly, transmuted to gold in the flickering orange glow.

“Morgrugyn,” she said, and now I knew the old woman’s Druid name, though not yet its meaning. “You said earlier this evening that the Dark, like the Light, seeks a particular consciousness to manifest through. But doesn’t the world around us manifest both light and dark all the time, already? Why the need for specific individuals — people, or spirits, gods, other beings? Why does there have to be a designated ‘Order’ at all for this to happen? Isn’t this just already a part of the weave of things?”

“Daughter, the dark and light halves spiral up through consciousness like two vines that curl and climb round a support. They flower most vividly and distinctly through consciousness. It’s true they often seek the easiest channel to flow through, and they pervade all things, as you said, working through all those many channels. But what is ‘easy’? A developed consciousness in a manifest being that is active on all the planes affords an unusually vital and, I will say, attractive channel.”

Morgrugyn paused for a sip from her water bottle, then continued. “A paradox — the Dark is as bright as the Bright is dark. For there is a kind of brightness in the Dark, focused through consciousness, that draws the awen in and gives it life. Charisma, to give another example, chooses its favourites from both halves. There is a ‘sinister appeal,’ as it’s been called, to certain persons and things. It’s the intention of a consciousness that makes the Dark or Bright so intense, so polarizing and forceful. Energy all around us still continuously gathers and diffuses, always dancing, here in a growing forest, there in an earthquake or volcano, one slower, the other faster. The Dance rises and subsides, subsides and rises again, which is why the tide, the moon, the seasons, the ritual Wheel of the Year, the give and take of bodies in lovemaking, the cycles of death and rebirth, are all such splendid teachers of this rhythm.”

“You seem to be arguing against your earlier point,” the younger woman said. “Doesn’t everything move toward equilibrium? And it’s been doing so for a really long time, long before humans appeared. Any Order, even a ‘dark’ one, is part of that equilibrium, isn’t it? Why do we suddenly need to worry?”

“Not suddenly. Everything does indeed ceaselessly seek out equilibrium. But when humans appeared, so did new opportunities for consciousness and manifestation of the equilibrium in new forms and patterns. Branching or diverging is one of things the universe ‘likes’ to do. And it makes sense to speak in such terms as ‘liking.’ We can see it in patterns as substances crystallize, we see it in snowflakes, in plants growing, in thoughts and ideas unfolding, in the outflung arms of spiral galaxies, in the whorls of seashells, in human groups and institutions which form and split and regroup and dissolve and are reborn. We see it in relationships, and we see it in new stars and planetary systems forming. The word, the idea of equilibrium, can mislead us, because people think ‘changeless.’ But equilibrium in this case is dynamic. It’s a living thing. The addition of consciousness to the local equilibrium — to this planet or solar system, which stretches the sense of ‘local,’ I admit — means that humans get to participate in the equilibrium in powerful ways. And they participate differently to how … how a rock does, for example.”

“So it’s our participation that makes the difference, then?”

“Yes,” said Morgrugyn, with a smile. “And an Order, as a potentially highly focused gathering of energy manifesting through human consciousness, can effect long-lasting changes in the equilibrium, for both ill and good together.”

“But those are human judgments, aren’t they?” asked Dragon, who had been frowning with concentration as he followed the thread of Morgrugyn’s argument. “What we consider good or bad may not be the same thing as what’s good or bad from a non-human standpoint.”

“The loss of branching or diversity, whatever else we think of it, means lives lost, animal and human, and a decline in equilibriating ability. With fewer options, an equilibrium deteriorates in stability. And increasingly violent shifts can shove an equilibrium to a new balance point that is far less conducive to the richness of lives we have known. Yes, that’s a judgment rendered largely from a human standpoint, but it does concern more than human lives. Some Orders and human groups may advocate from non-human standpoints, like those of a god-form. Yes, Lugh or Thor or Isis or Yemaya may perceive and cherish and pursue longer, deeper goals than most humans. However, they never cherish goals against life. But some few Orders work from standpoints that value some specific advantage or benefit at a cost most of us would refuse to pay, or even consider. From what I’ve seen of them, Urdd Awen Ddu is one of those latter Orders. And the nature of their “darkness”? It lies in this: the price they are planning for all of us to pay to achieve their goals — with neither our knowledge nor our consent.”

/|\ /|\ /|\

Part 3 coming soon

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

“Now, my daughters and sons,” said the old woman, “because all things in this world dance with their opposites, and the Bright is the left hand of the Dark, it is meet that I, who am old and may not live to see the end of the next winter, should be the one who tells you of the Order of the Black Awen, Urdd Awen Ddu.”

She paused, and seeing her shiver I drew the blanket more closely around her. There was just a handful of us still gathered round the fire. Her words might have seemed overblown or contrived at any other time. But the fire and the evening and the mead had each done their work. We were ready to hear almost anything. The dew had descended a couple of hours ago, but the night chill only now was lapping at our skin. Dragon built up the fire again, and raked the coals together so the new logs would kindle sooner. The old woman smiled at us and continued.

“I give the Order its Welsh name, too, because it offers a valuable lesson. Taken apart from its meaning, the sound of it is lovely: oorth ah-wen thoo.* And so too its birth. All things carry in their breasts a spark of the Imperishable Flame at the heart of the world, the breath of the Formless. Anciently the Wise of the East knew this, and the Sage of the Way wrote in his book, ‘From the One comes Two; from the Two, Three; and from the Three the Ten Thousand Things.’ Without that balance, chaos follows. We might even welcome the appearance of the counterpart, the opposite, in a way, without doubting it will cost us dearly when we face it, as we eventually must. But it is the third of the Three that issue from the One which we will turn to for our way forward.”

She spoke now quite deliberately, not expecting questions as she had earlier, when a lot of good-natured banter enlivened the fire circle, and anyone who held forth and pontificated, never mind the subject, soon had to give it up and relearn if necessary the arts of true conversation, of actual give and take, rather than expecting a reverent silence from the rest of us. That earlier hour also saw the old woman depart for a nap after a brief appearance, so that she would be fresh for later. Which was now. And now we wanted her to hold forth, because she had something of considerable value to share with us, and because what she said was new to us. The singing and drinking carried us here, where we needed to listen. Night had shaped this place and space. So we were quite content mostly to listen and ponder her words.

Questions, however, bothered her not at all, and she sat at her ease when we occasionally asked them. Earlier she asked a good few of her own, though her hearing sometimes played tricks on her. Someone inquired where she had first encountered this Order, and this led to a sad but funny story that must keep for another time. Though she must have been in her late nineties and stooped, and the age-spotted skin of her hands slid loosely over her bones, her thought darted swift and sure, and her gaze out of eyes filmy with cataracts was nonetheless keen.

“Now this Order, dedicated as it is to things we must oppose who cherish the balance, comes into existence because we exist. Each thing calls forth its companion, its counterpart, and Dark is ever the companion and counterpart of Bright. It is a peculiar and perilous folly of these days to suppose we can all ‘just get along.’ We cannot. The world simmers always, and sometimes, as it must, it spills over into open conflict. When a Dark Order forms, the action of the Light has made some advance, yes, but it also stands in peril for that reason. The cause of the Light (or the Dark, for all that) is no mere cliche or child’s fantasy, and such a challenge from the Dark, one that claims and divides the awen, is one that we must answer.”

/|\ /|\ /|\

*the th of this respelling of the sound dd in Welsh urdd and ddu is voiced, as in English this, them, not as in thick, thin.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

J3D — “Just Three Drops” — is shorthand for the experience of Gwion Bach, the servant boy in the Welsh story who tends the cauldron of transformation for … how long? Yes, perhaps you’ve already guessed it — a year and a day. The magic brewing in the cauldron is, alas, destined for another, and Gwion is sternly charged to keep the fire carefully. Never let it die out. Always maintain a steady flame. Haul wood, carry water. Be sure the contents continue to simmer and seethe and stew as they slowly wax in power.

After Gwion faithfully tends the fire for that long, sooty and tedious year of drudgery, at last the mixture nears completion. One day the cauldron boils up, spattering a little, and three drops spill onto Gwion’s hand, burning it. Instinctively he lifts the burn to his mouth to soothe it. Voila! In that moment he imbibes the inspiration, awen, chi, spirit, elemental force meant for another, and so begins the series of transformations that will make him into Taliesin, Bard and initiatory model for many Druids and others who appreciate good wisdom teaching.

An accident? Has Gwion’s year of service led to this? Was it sheer luck, a “simple” case of being in the right place at the right time? Does blind chance govern the universe? (Why hasn’t something like this happened to ME?) Is the experience repeatable? Where’s a decent cauldron when you need one? Can I get those three drops to go? J3D caps, shirts, towels, belt-buckles on sale now! Buy 3 and save.

J3D in some ways can mislead you. “Visit us for your transformational needs. Just three drops, and you too can become a Bard-with-a-capital-B!” The ad seduces with the promise of something for almost nothing. (May the spirits preserve us from clickbait Druidry!) Such glibness leaves out the inconvenient preparation, the lengthy prologue, the awkward context, the unmentioned effort, the details of setting everything depends on. (Doesn’t it always?) It’s true: Just three drops are all you need, AFTER you’ve done everything else. They’re the tipping point, the straw that moved the camel to its next stage of camel-hood. J3D, J3D, J3D! The crowds are chanting, they’re going wild!

Curiously, J3D is a key to getting to the place and time where J3D’s the key. It’s the sine qua non, the “without which not,” the essential component, the one true thing.

Fortunately, the way the universe appears to be constructed, we can locate, if not the ultimate J3D, still very useful versions of it, tucked away in so many nooks and crannies of our lives. If I didn’t know better, I’d even suspect that the universe in its surprising efficiencies has shaped every environment for optimum benefit of the species that have adapted themselves to live there. Which means pure change and perfect intention are pretty much the same thing, depending on the local awen you’re sipping from. Paradox is the lifeblood of thinking about existence. Or as one of the Wise once put it, the opposite of an average truth may well be a falsehood. But the opposite of a profound truth is often enough another profound truth.

When the first glow is gone, the spark has dimmed, the lustre has worn off, you’re probably at the first drop. When any possibility of an end has faded from sight, when you’ve forgotten why you’re doing it and you’re going through the paces out of what feels like misplaced devotion or pure inertia, if you even have enough energy to stop and think at all, you’re likely in the neighborhood of drop 2. When you’ve given up theories, regrets, anger, hope, denial, bargaining, and grief itself, and you simply tend that fire because you’re able to tend that fire, and lost in reverie you feel a sudden burning, the third drop announces itself.

At that point the experience may well appear as three quick drops in succession, erasing any memory of the earlier drops, the practice for the final event, slog to get to that point. Or the long intervals between each drop find themselves renewed, deepened, intensified in the pain the third drop brings. Somehow, though, all that has gone before either falls away, or the pain of change is so intense it fills your whole awareness, crowding out all else, a white and scalding fire from horizon to horizon. Or in a vast hall of silence, the only sound is a whisper of the soft flesh of your hand soothed by tongue and lip. Then you know the transformation is upon you.

J3D.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

A (dreamily): If you call, they will respond …

B (annoyed): Who are “they” and why should I care?

A: Oh, well, uh, you don’t need to care. I was just saying …

B: Then why mention it?

And thus another chance at discovery gets shut down. Yes, of course it’s happened to me as it no doubt has to you, and more than once. But I’m more interested in how often I’ve provided this unkind service for somebody else. If in the midst of human self-pity or fatigue or temper, I can’t muster enthusiasm for another manifestation of Spirit, can I at least offer silence? (These days that can count as an invitation.) My own actions I have some control over. I’m not answerable for other people’s, thank the gods.

Fortunately, the awen does not depend on human kindness or indifference. It flows from deeper wells, and it will out. I can slow it, temporarily shunt it aside from blessing me or the local situation or the whole cosmos, but never altogether block it. The Galilean Master knew this: “I tell you, if you keep quiet the stones will cry out.”*

/|\ /|\ /|\

The call went out and I responded. In this case, for afternoon “exploratories” — informal classes in a skill or craft at a neighborhood high school, after regular classes end for the day. I jumped through the hoops of paperwork, the routine police background check, got fingerprinted (digitally), so I could then offer a six-session class on conlanging.** I even went to a school meeting a week ago to talk it up with my “Top Ten Reasons to Join the Conlang Class.”*** Now I’m waiting to see if initial interest turns into enrollments and makes the class happen. The teacher who organizes the exploratories helped: he’s a fan of conlangs himself and knows a few kids he thinks might find them “just the right amount of weird to be cool,” as he put it.

So what’s particularly Druidic about conlangs? Well, not everything has to demonstrate an immediate link to Druidry, does it? Conlanging is something this Druid does, and you’ve read this post up to this point, so stay with me. But if you think about it, language and language craft are after all domains of the Bard, and my Bardic self is always responding to the call of language and words and sound and human awareness of the cosmos as we talk and think about it.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Take the Welsh phrase from a recent post, y gwir yn erbyn y byd, and you’ve got a fine example of conlanging to work with.

(Wait, you say. Welsh is a real language. Well, so are many conlangs, if by “real” you mean that they exist and people use them to communicate and you can say anything with them that you can say in your native language. How much more “real” can anything be? If by “real” you mean they have thousands or millions of speakers, well, Welsh stands around the 500,000 speaker mark, depending on who’s counting. Many Native American languages have only a few dozen speakers left. Mere numbers are just that. Besides, as a wise one once said, some of the same minds that created all human languages are at work on conlangs. At this point, the word real starts to look less than altogether useful and more like a comment on the person who uses it.)

One of the initially daunting things about a foreign language is simply that it “looks (and sounds) foreign.” But this Welsh phrase has almost a one-for-one correspondence to English. The different words mask vast similarities that make both Welsh and English human languages, and make them learnable and usable. Here’s a word-for- word rendering of the Welsh:

y gwir yn erbyn y byd

the truth in despite (of) the world

What this means for conlangers is that surface differences are one key to conlanging.

(The “fake glasses and a moustache” school of conlanging gets a lot of mileage out of surface differences. Make your conlang too much of a cleverly disguised English, though, and conlangers will call you on merely making a relexification, which is a learned way of saying you’re just replacing word by word, rather than creating a unique language where a one-for-one translation is usually impossible. But don’t worry: many conlangers go through a fascination with relexification. Tolkien himself made a childhood relex called Nevbosh, which means New Nonsense. He and his cousins played with it and even could make limericks in it. He probably also learned a fair deal from its making.)

Welsh and English both have articles: the and y(n). They both have nouns. They make phrases in a very similar way. And sentences. Yes, Welsh and English word order differs in a few important ways. Sounds interact somewhat differently. From a conlanger’s point of view, that’s window-dressing to play with.

In English we say “just add -s to make a noun plural.” What could be simpler? So you may shake your head when you hear that Welsh forms plurals in over a dozen different ways. But consider: English “cats” adds -s. But “dogs” adds a -z, though it’s still written -s. And “houses” adds an -iz, though it’s written -es. Add in ox/oxen, wolf/wolves, sheep/sheep, curriculum/curricula, and so on, and you get a different picture. Native speakers make most of these shifts instinctively. The same happens in other languages. That’s the reason that when a child says “I goed to school” we may think it’s cute. We may correct her (or not), but if we think about it a moment, we understand that she’s mastered the rule but not yet the exception.

All hail the awen of human intelligence!

Go a little ways into conlanging, and you may discover a taste for something different from (here British English requires “to” rather than “from”) SAE — “Standard Average European.” There’s a rather dismissive word for it in the conlanging world: a “Euroclone” — a language which does things that most other European languages do. Nothing wrong with it. I’ve spent years elaborating more than one of my own. But many other options are out there to try out, in the same way that the eight notes of an octave aren’t the only way to play the available sonic space.

Take Inuit or Inuktikut. Just the feel of the names shows they inhabit a different linguistic space than English does. I-nuk-ti-kut. For a conlanger, that’s a sensuous pleasure all its own, a kind of musical and esthetic delight in the differences, the revelation of another way to configure human perception and describe this “blooming buzzing confusion” as psychologist William James characterizes a baby’s first awareness of the world. But of course that “BBC” does get converted into human language. (Language origins continue to fascinate researchers.)

In the case of Inuktikut, “… words begin with a root morpheme to which other morphemes are suffixed. The language has hundreds of distinct suffixes, in some dialects as many as 700. Fortunately for learners, the language has a highly regular morphology. Although the rules are sometimes very complicated, they do not have exceptions in the sense that English and other Indo-European languages do.” (I’ll be lifting material wholesale from the Wikipedia entry.)

Agglutinating or polysynthetic languages like Inuktikut tend to be quite long as result of adding suffix to suffix. So you get words like tusaatsiarunnanngittualuujunga “I can’t hear very well” that end up as long as whole English sentences. As the entry innocently goes on to acknowledge, “This sort of word construction is pervasive in Inuit language and makes it very unlike English.”

Tusaatsiarunnanngittualuujunga begins with the word tusaa “to hear” followed by the suffixes tsiaq “well”; junnaq “be able to”; nngit “not”; tualuu “very much” and junga “1st person singular present indicative non-specific.” The suffixes combine with sound changes to make the word/sentence Tusaatsiarunnanngittualuujunga. So if you want to create something other than English or your average Euroclone, Inuktikut is one excellent model to study for a glimpse of the range of what’s possible.

Now if this sort of thing interests you, you’re still reading. If not, you’re saying “Well, he’s just geeked out on another post. Where’s the Druidry, man?” For me, Druidry has wisdom and insight about all human activity, and can deepen human experience. I’m in it for that reason. May you find joy and wisdom as you live your days and follow your ways.

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Luke 19:40

**conlanging: the making of con(structed) lang(uages). Tolkien’s one of our patron saints. You can find other posts about conlanging on this blog here. Here’s the obligatory Wikipedia entry. And here’s a link to the Language Creation Society., cofounded by David Peterson, one of the best-known conlangers working today, and creator of Dothraki, Castithan, Sondiv, and a dozen other conlangs.

***Top Ten Reasons to Join the Conlang Class

10: Languages are cool — conlangs are even cooler: Game of Thrones has Dothraki & Valyrian, Avatar has Na’vi, Star Trek has Klingon, Lord of the Rings & The Hobbit have Elvish, there’s Castithan in Defiance, Sondiv from Star-Crossed, Esperanto, Toki Pona, etc.

9: I’ve been conlanging for decades, can help you get started, gain a sense of the possibilities, & keep going after the class ends.

8. Making conlangs can help you go “inside language” (like Lewis said of Tolkien) & discover amazing things about our most powerful human tool.

7: Conlanging is one of the cheapest arts & crafts I know: all you really need is pen & paper. (Of course, a computer can help.)

6: Nerds need to stick together or our 3 big Nerd Secrets will get out — we’re all nerds in some way, nerds are cool, & nerds have more fun.

5: You’ll learn enough to participate in the international conlang community which is very active online & also in print.

4: You too can learn to say things like Klingon Tlingan Hol dajatlaH & Valyrian sikudi nopazmi & Elvish Elen sila lumen omentielvo — & more importantly, you’ll know what they actually mean.

3: You can join the Language Creation Society & create languages for others for fun & profit.

2: You can keep a secret diary or talk to friends in your conlang & no one else will know what you’re saying.

1: You’ll have your own conlang & script by the end of the last class.

[ 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30]

Sometimes an evocative line can serve up a good day’s worth of Druid meditation. An article on schizophrenia in the current New Yorker offers this fabulous paragraph on the development of the brain, with its potent last line:

The human eye is born restless. Neural connections between the eyes and the brain are formed long before a child is born, establishing the wiring and the circuitry that allow her to begin visualizing the world the minute she emerges from the womb. Long before the eyelids open, during the early development of the visual system, waves of spontaneous activity ripple from the retina to the brain, like dancers running through their motions before a performance. These waves reconfigure the wiring of the brain—rehearsing its future circuits, strengthening and loosening the connections between neurons. (The neurobiologist Carla Shatz, who discovered these waves of spontaneous activity, wrote, “Cells that fire together, wire together.”) This fetal warmup act is crucial to the performance of the visual system: the world has to be dreamed before it is seen.

I find myself wanting to draw out this image, to extend its reach, then try out those extensions to see whether and how they might be true. Dream a world and you can see it. Sing before you can hear anything, let alone the music of the spheres. Limn the deeds and character of a deity, and she begins to manifest at the invitation of this earliest devotion. Imagine with whatever awen drops into your awareness, and the transformation of that subtle primordial seed-stuff proceeds apace. We nurture energies and impulses, not merely passively experiencing them, and they weaken and die or grow and thrive in the womb of human consciousness. How many things are literally unthinkable until that first person somewhere thinks them? What can I give birth to today? (Schizophrenia, and creativity too, have physical correlates — according to research cited in the article they both issue from the processes mentioned of strengthening and loosening connections between neurons.)

Old Billy Blake, sometime-maybe Druid, maybe madman, says in the last lines of his poem “Auguries of Innocence“:

We are led to Believe a Lie

When we see [with] not Thro the Eye

Which was Born in a Night to perish in a Night

When the Soul Slept in Beams of Light

God Appears & God is Light

To those poor Souls who dwell in Night

But does a Human Form Display

To those who Dwell in Realms of day.

Praise be then to the Keepers — and Seekers — of such Double Vision. And I ask myself: Can we see the world whole in any other way? Hail, Day-dwellers, Night-dwellers, Walkers of Both Worlds!

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: “Infinity”

The Awen I sing,

The Awen I sing,

From the deep I bring it,

A river while it flows,

I know its extent;

I know when it disappears;

I know when it fills;

I know when it overflows;

I know when it shrinks;

I know what base

There is beneath the sea.

(lines 170-179, Book of Taliesin VII, “The Hostile Confederacy“)

Oh, Taliesin, how do you know these things? I say to myself. How is it you enchant yourself into wisdom?

I have been a multitude of shapes,

Before I assumed a consistent form.

I have been a sword, narrow, variegated,

I have been a tear in the air,

I have been in the dullest of stars.

I have been a word among letters,

I have been a book in the origin.

OK, you know it because you’ve been it, I say to myself and the air.

When I sing, I hear a music that both exists and does not exist until I open my mouth. We create in the moment of desire and imagination. “From the deep” we bring things that flow like rivers while we sing. But before the song, or after?

Contrary to what I may think in the moment, so many things are matters of doing rather than believing. Challenges behave much the same as joys. When I’m afraid, I have a chance to show courage. What else does courage mean but to be afraid — and to attempt the brave thing anyway?

And when I sing, that takes a kind of courage too. I mean by this that singing when the sun shines is easy enough. Necessary, too. A gift. But singing in the dark, singing in pain, singing in uncertainty — or singing in joy when joy itself is suspect and the times are bad — there’s a song of power Taliesin would recognize.

The Awen I sing,

From the deep I bring it.

Another tool for my tool-kit. Sing it and you bring it. Make it come true when before, without you, it not only hasn’t yet arrived, it won’t and can’t arrive until you do.

IMAGE: Taliesin.

Sunrise, are you waiting for that sliver of moon to invite you? This time of year I’m up before you, and waiting in the perfect frozen peace of January pre-dawn.

Sunrise, are you waiting for that sliver of moon to invite you? This time of year I’m up before you, and waiting in the perfect frozen peace of January pre-dawn.

Slowly our snow-covered fields flower from purple to gray to white, and then bloom golden with light. A cardinal with pinfeathers puffed against the cold ignites the snow when he lands beneath the bird-feeder, all impossible red. Ah, day at last, over the eastern hill you come, and here we are, in the eye of the sun, loving the light though we may forget to say so. I will say so now, while I remember. All praise for light inside and out!

Yes, I can be a Druid in the life of a day. But bring on night and darkness and my Druidry can suffer a sea-change. You know you’re a Druid when death moves you not at all, says a tendril of awareness. When you may not even notice you’ve changed realms. Well, but I’m not there yet, I reply. I have no trouble with death. I drop into darkness each time I fall asleep. It’s dying that troubles me. And others’ deaths that are hard to take, though with the gift of Sight we may know them after and visit them still. It’s the body comfort I miss, voice and touch and the daily-ness of a life lived next door to my own. I know you’re around, Ancestors without your skins on, but I miss you here.

I light this flame to gift the darkness, not contend with it. Each has its place, here in Abred*. “Know all things, be all things, experience all things”: some say this is our destiny, as we move through the circles of existence. Maybe. Not sure yet. Don’t need to be. This circle right now, right here, keeps me plenty occupied.

Nine awens for the day

for the day’s choices

and gifts easy and difficult.

Nine awens for the gods

unknown and known who grace us

with the Breath of Asu,

sound and light both.

Nine awens for you, little soul,

beast, bird or human, watching

at the gates of Abred*

for the flower of destiny

to unfold its next petal

as you become.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: sunrise.

*Abred. The great Revival Druid and brilliant forger, Iolo Morganwg, wrote in his compendium of wisdom and fabrication the Barddas that all beings move slowly from Annwn, the unformed, to Abred, the first world, our present circle, “probation,” and from there to Gwynvyd, the “white world” of the next advance and “perfect freedom,” and on from there to Ceugant, “infinity.” And the way there is long and full of experiences until, ripe with knowing all things each circle has to teach us, we take a step to the next.

Do I “believe” it? That’s not the important question to me, or to many Druids. How well does it explain things? What can I learn from it? Those are the important questions. Whether it’s “true” or not is quite beside the point. I’m not interested in creedal religion; that’s one reason I’m a Druid, after all. I don’t have a statement of faith; I have a practice that includes various beliefs that evolve as I do. I don’t want to sit in the restaurant and wait to be served from another’s choice, to use Philip Carr-Gomm’s image (go to 4th paragraph). I want to work in the kitchen, help it come together for myself. This is Abred, the world of probation, after all — of proving and testing and trying out. So I’m game — I try it out, try it on for size.

Updated 4 August 2015

Greer, John Michael. The Gnostic Celtic Church: A Manual and Book of Liturgy. Everett, WA: Starseed Publications (Kindle)/Lorian Press (paper), 2013. NOTE: All quotations from Kindle version.

Quick Take:

A valuable resource for those wishing to explore a coherent and profound Druid theology and to develop or expand a solitary practice. Greer offers pointers, reflections, principles — and a detailed set of rites, visualizations and images emerging from both AODA Druidry and Gnostic-flavored Celtic Christian magic practice.

Expansive Take:

John Michael Greer

John Michael Greer continues to advance ideas and books that provoke and advocate thoughtful, viable alternatives to dysfunctional contemporary lifestyles and perspectives. The Gnostic Celtic Church takes its place among a growing and diverse body of work. Author of over thirty books, blogger (of the influential weekly Archdruid Report, among others), practicing magician, head of AODA (Ancient Order of Druids in America), “Green Wizard,” master conserver and longtime organic gardener, Greer wears lightly a number of hats that place him squarely in the ranks of people to read, consider, and take seriously, even if you find yourself, like I do, disagreeing from time to time with him or his perspectives. In that case, he can still help you clarify your stance and your beliefs simply by how he articulates the issues. In person (I met him at the 2012 East Coast Gathering), he is witty, articulate, widely informed, and quick to dispose of shoddy thinking. (As you can ascertain from the picture to the right, he’s also has acquired over the decades a decidedly Druidic beard …)

What all Gnostic traditions share, Greer notes, is that

personal religious experience is the goal that is set before each aspirant and the sole basis on which questions of a religious nature can be answered — certain teachings have been embraced as the core values from which the Gnostic Celtic Church as an organization derives its broad approach to spiritual issues. Those core teachings may be summarized in the words ‘Gnostic, Universalist, and Pelagian’ which are described in this book.

The Gnostic Celtic Church (GCC) may appear to step away from direct engagement with contemporary issues that have been the focus of Greer’s blog and recent books: peak oil, the decline of the West and its imperial overreach, and ways to begin laying the foundations and shaping a new, more balanced and truly green post-oil civilization that can arise over the next few centuries.

The Gnostic Celtic Church (GCC) may appear to step away from direct engagement with contemporary issues that have been the focus of Greer’s blog and recent books: peak oil, the decline of the West and its imperial overreach, and ways to begin laying the foundations and shaping a new, more balanced and truly green post-oil civilization that can arise over the next few centuries.

Instead of avoiding what amounts to an activist engagement, however, the book comes at these issues indirectly, outlining a set of core practices and perspectives for what AODA intends as “an independent sacramental church of nature spirituality.” The “independent sacramental movement ranks among the most promising stars now rising above the horizon of contemporary spirituality,” Greer observes in his introduction. Its freedom from the bonds of creed and doctrine has helped carry it to fresh insights and creativity, and deep applicability to the seeking that characterizes our era of “spiritual but not religious.”

What, you may be asking, does this have to do with Druidry? A lot. Or why would a Druid group include a “church” in the middle of its affairs? Read on, faithful explorer.

To examine in turn each of the three terms that Greer puts forth, the GCC is “Gnostic” because it affirms that “personal experience, rather than dogmatic belief or membership in an organization, can form the heart of a spiritual path.” This sensibility accords well with most flavors of Druidry today. While there is an admitted theme of ascetic dualism and world-hating in some currents of Gnostic thought, Greer provides useful context: “… this was only one aspect of a much more diverse and creative movement that also included visions of reality in which the oneness of the cosmos was a central theme, and in which the body and the material world were points of access to the divine rather than obstacles to its manifestation.”

The GCC is also “Universalist.” Among other early Church leaders, the great mystic Origen (184-254 CE) taught that “communion with spiritual realities is open to every being without exception, and that all beings — again, without exception — will eventually enter into harmony with the Divine.” The Universalist strain in Christianity is perhaps most familiar to most people today in the guise of Unitarian Universalism, a relatively recent (1961) merger of two distinct movements in Christianity. A Universalist strain has been “central to the contemporary Druid movement since the early days of the Druid Revival” (ca. 1600s) and “may be found in many alternative spiritual traditions of the West.” Both Gnostic and Universalist links existed within AODA Druidry when Greer was installed as Archdruid in 2003. For another perspective, check out John Beckett’s blog Under the Ancient Oaks: Musings of a Pagan, Druid and Unitarian Universalist.

The GCC is also “Universalist.” Among other early Church leaders, the great mystic Origen (184-254 CE) taught that “communion with spiritual realities is open to every being without exception, and that all beings — again, without exception — will eventually enter into harmony with the Divine.” The Universalist strain in Christianity is perhaps most familiar to most people today in the guise of Unitarian Universalism, a relatively recent (1961) merger of two distinct movements in Christianity. A Universalist strain has been “central to the contemporary Druid movement since the early days of the Druid Revival” (ca. 1600s) and “may be found in many alternative spiritual traditions of the West.” Both Gnostic and Universalist links existed within AODA Druidry when Greer was installed as Archdruid in 2003. For another perspective, check out John Beckett’s blog Under the Ancient Oaks: Musings of a Pagan, Druid and Unitarian Universalist.

“Pelagian,” the third term, is perhaps the least familiar. This Christian heresy took its name from Pelagius (circa 354-420 CE), a Welsh mystic who earned the ire of the Church hierarchy because of his emphasis on free will and human agency. Pelagius taught, as Greer briskly characterizes it, that “the salvation of each individual is entirely the result of that individual’s own efforts, and can neither be gained through anyone else’s merits or denied on account of anyone else’s failings.” Of course this teaching put Pelagius at odds with an orthodoxy committed to doctrines of original sin, predestination, and the atonement of Christ’s death on the cross, and to policing deviations from such creeds. A Pelagian tendency remains part of Celtic Christianity today.

Greer draws on the history of Revival (as opposed to Reconstructionist) Druidry and notes that the former places at its center some powerful perspectives on individual identity and destiny.

Each soul, according to the Druid Revival, has its own unique Awen [link: an excellent (bilingual) meditation on Awen by Philip Carr-Gomm]. To put the same concept in terms that might be slightly more familiar to today’s readers, each soul has its own purpose in existence, which differs from that of every other soul, and it has the capacity — and ultimately the necessity — of coming to know, understand, and fulfill this unique purpose.

None of this is intended to deny the value of community — one of the great strengths of contemporary Druidry. But we each have work to do that no one else can do for us. In keeping with the Druid love of threes, what we do with the opportunities and challenges of a life determines where we find ourselves in the three levels of existence: Abred, Gwynfydd and Ceugant. These are a Druid reflection of an ancient and pan-cultural perception of the cosmos. Greer delivers profound Druid theology as a potential, a map rather than a dogma. “It is at the human level that the individual Awen may become for the first time an object of conscious awareness. Achieving this awareness, and living in accord with it, is according to these Druid teachings the great challenge of human existence.” Thus while the Awen pervades the world, and carries all life, and lives, in its melody and inspiration, with plants and animals manifesting it as instinct and in their own inherent natures, what distinguishes humans is our capacity to know it for the first time — and to respond to it with choice and intention.

Thus, Greer outlines the simplicity and depth of the GCC:

… the rule of life that the clergy of the Gnostic Celtic Church are asked to embrace may be defined simply by these words: find and follow your own Awen. Taken as seriously as it should be — for there is no greater challenge for any human being than that of seeking his or her purpose of existence, and then placing the fulfillment of that purpose above other concerns as a guide to action and life — this is as demanding a rule as the strictest of traditional monastic vows. Following it requires attention to the highest and deepest dimensions of the inner life, and a willingness to ignore all the pressures of the ego and the world when those come into conflict, as they will, with the ripening personal knowledge of the path that Awen reveals.

All well and good, you say. The basis for a mature Druidry, far removed from the fluff-bunny Pagan caricatures that Druids still sometimes encounter. But what about down-to-earth stuff? You know: rituals, visualizations, prompts, ways to manifest in my own life whatever realities may lie behind all this high-sounding language.

Greer delivers here, too. Though membership and ordination in the GCC require a parallel membership in AODA, the practices, rites and visualizations are set forth for everyone in the remainder of the book. That’s as it should be: a spiritual path can take either or both of these forms — outward and organizational, inward and personal — without diminution. And those interested in ordination in other Gnostic organizations will probably already know of the variety of options available today. Greer notes,

Receiving holy orders in the GCC is not a conferral of authority over others in matters of faith or morals, or in any other context, but an acceptance of responsibility for oneself and one’s own life and work. The clergy of the GCC are encouraged to teach by example, and to offer advice or instruction in spiritual and other matters to those who may request such services, but it is no part of their duty to tell other people how to live their lives.

If, upon reflection, a candidate for holy orders comes to believe that it is essential to his or her Awen to claim religious or moral authority over others as part of the priestly role he or she seeks, he or she will be asked to seek ordination from some other source. If one who is already ordained or consecrated in the GCC comes to the same belief, in turn, it will be his or her duty — a duty that will if necessary be enforced by the Grand Grove [of AODA] — to leave the GCC and pursue another path.

The ceremonies, rituals and meditations include the Hermitage of the Heart, the Sphere of Protection, the Calling of the Elements, the Sphere of Light, a Solitary Grove Ceremony (all but the first derive from AODA practice), and a Communion Ceremony that ritualizes the “Doctrine of the One”:

I now invoke the mystery of communion, that common unity that unites all beings throughout the worlds. All beings spring from the One; by One are they sustained, and in One do they find their rest. One the hidden glory rising through the realms of Abred; One the manifest glory rejoicing in the realms of Gwynfydd; One the unsearchable glory beyond all created being in Ceugant; and these three are resumed in One. (Extend your hands over the altar in blessing. Say …)

Included also are seasonal celebrations of the four solar festivals, the two Equinoxes and Solstices, ordination ceremonies for priests, deacons and bishops, advice on personal altars, morning prayer, evening lection or reading, and visualizations that recall Golden Dawn visualizations of rays, colors and symbols.

At a little over 100 pages, this manual in its modest length belies the wealth of material it contains — plenty to provide a full Gnostic Celtic spiritual practice for the solitary, enough to help lead to a well-informed decision if ordination is the Call of your Awen, and material rich for inspiration and spiritual depth if you wish to adapt anything here to your own purposes.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: John Michael Greer; GCC book cover; flame.

In this, the dark half of the year, we may face things that don’t have faces. One way we deal with this is by telling stories.