Archive for the ‘nature’ Tag

Jedediah Purdy

In “The New Nature” (Boston Review, Jan 11, 2016), author Jedediah Purdy opens provocatively when he asserts that the current age “adds nature to the list of things we can no longer regard as natural.” His essay’s not easy going, but it definitely rewards close reading — and re-reading. Purdy’s ultimate argument is that with the profound impact of our human presence on the planet, “nature is now a political question.”

How he pushes beyond this seeming truism is significant. Those of us alive today “confront the absence of political institutions, movements, or even widely shared sentiments of solidarity and shared challenges that operate on the scale of the problems concerning resource use and distribution we now face.”

Of course, the challenges that humans have faced throughout our history frequently outpace our existing institutions, wisdom and capacity to take effective action. That’s one workable definition of “crisis,” after all. And the compulsions and sufferings of a crisis often catalyze the formation of just those institutions, wisdoms and capacities. (They also fail to do this painfully often, as we’ve learned to our cost.)

Of course, the challenges that humans have faced throughout our history frequently outpace our existing institutions, wisdom and capacity to take effective action. That’s one workable definition of “crisis,” after all. And the compulsions and sufferings of a crisis often catalyze the formation of just those institutions, wisdoms and capacities. (They also fail to do this painfully often, as we’ve learned to our cost.)

But Purdy’s contention goes beyond apparent truism or the obvious. Our current ecological predicament takes its shape as part of the third of three “revolutions of denaturalization.” The first of these is the realization that any political order is a human choice. The “divine right of kings” is out; flawed human agency is in. Whatever is “natural” about “the way things are” is what we’ve made and accepted. It decidedly does not inhere in the universe. It is not the will of any deity. (The caliph of Daesh/ISIL has no more claim to legitimacy than a local mayor. Humans put both of them in power. Humans can take them out.)

The second revolution, not surprisingly, concerns economics. Like politics, the “natural order of things” in a given economy is anything but natural. People aren’t destined by some cosmic law to be laborers, leaders, warriors, wealth-bearers, priests, etc. Humans choose how to feed and house themselves, what things have value, and who can gain access to them. Though nowadays we define prosperity in narrow terms, as one of my favorite political writers C. Douglas Lummis points out, “How and when a people prospers depends on what they hope, and prosperity becomes a strictly economic term only when we abandon all hopes but the economic one.”* Hope for more than a paycheck means a life based on more than money.

The third revolution hinges on nature. Purdy notes, “Both politics and the economy remain subject to persistent re-naturalization campaigns, whether from religious fundamentalists in politics or from market fundamentalists in economics. But in both politics and economics, the balance of intellectual forces has shifted to artificiality.” So too is “nature” subject to deification and renaturalization, and here the implications for modern Paganism and Druidry hit home.

Given the modern reflex abhorrence in many “organic” quarters towards anything “artificial,” it may take you a moment, as it did me, to move past such associations and hear what Purdy is actually claiming. To put it another way, keep doing what we’re doing, and we’ll keep getting what we’re getting. No god or demon (or magical elemental, set of “market forces” or cosmos) orders things this way — we do. Gaia, the clear implication is, won’t come to our (or Her) aid.

A religious re-naturalization of nature is therefore insufficient, whether it’s the RDNA (Reformed Druids of North America) gospel of “Nature is good” or Pope Francis’s emphasis on a divinely-ordered world of which we ought to be more compassionate stewards. Insofar as such a renaturalization or resacralization is part of any Druid program or agenda, it’s insufficient and perhaps even an obstacle. Only a political response, Purdy maintains, can begin to be adequate to the challenges of the Anthropocene Epoch– the human era we’re now in.

Thus, Purdy points out, “Even wilderness, once the very definition of naturalness, is now a statutory category in U.S. public-lands law.” The Sierra Club still markets this (outdated, in Purdy’s perspective) view as one of its touchstones: “In wilderness is the salvation of the world.” (By way of Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, paraphrasing Thoreau’s Walden; Thoreau actually wrote preservation.)

Thus, Purdy points out, “Even wilderness, once the very definition of naturalness, is now a statutory category in U.S. public-lands law.” The Sierra Club still markets this (outdated, in Purdy’s perspective) view as one of its touchstones: “In wilderness is the salvation of the world.” (By way of Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, paraphrasing Thoreau’s Walden; Thoreau actually wrote preservation.)

We often uncritically hold to a romantic (and Romantic) notion of the natural world as pure or unspoiled, a realm or order which is, at least in a few surviving locations, uncontaminated by human agency. But, Purdy continues, “as a practical matter, ‘nature’ no longer exists independent of human activity. From now on, the world we inhabit will be one that we have helped to make, and in ever-intensifying ways.”

Purdy is not anti-nature by any means, as a cursory reading of his essay might at first suggest. He’s not a foe to demonize or take down on Twitter, if you’re a radical Pagan/environmentalist. But the challenges he depicts are real. As a Druid I need to pay attention when he writes things like this:

To invoke nature’s self-evident meaning for human projects is to engage in a kind of politics that tries, like certain openly religious arguments, to lift itself above politics, to deny its political character while using that denial as a form of persuasion. It is akin in its paradox to partisan mobilization in favor of constitutional originalism, which legitimates solutions to political problems by recourse to extra-political criteria—in the present case, what nature was created to be, or self-evidently is.

Such arguments succeed by enabling their advocates to make the impossible claim that only their opponents’ positions are political, while their own reflect a profound comprehension of the world either as it is or was intended to be.

Is nature (or Nature) “self-evidently” anything? If so, what? Do Druids and Pagans generally have any special insight to share that can respond to views like Purdy’s with any kind of authority or credibility? Can we demonstrate a “profound comprehension of the world” in terms that matter and more importantly will shape policy? For environmentalists (and for Pagans, though Purdy doesn’t name them), “inspiration and epiphany in wild nature became both a shared activity and a marker of identity. They worked to preserve landscapes where these defining experiences were possible.”

But throughout human history, Purdy notes, various and successively changing ideals of nature have underpinned diverse economic and political arrangements that always consistently disenfranchise a designated fraction of humans. Whether slaves, minorities, women, aboriginal peoples, immigrants, certain racial or ethnic groups, someone always gets the short end of the stick from these idealizations of “nature.” To hold the natural world to anything but a democratic politics, Purdy says, is to exclude, to perpetuate injustice, and to oppress.

But throughout human history, Purdy notes, various and successively changing ideals of nature have underpinned diverse economic and political arrangements that always consistently disenfranchise a designated fraction of humans. Whether slaves, minorities, women, aboriginal peoples, immigrants, certain racial or ethnic groups, someone always gets the short end of the stick from these idealizations of “nature.” To hold the natural world to anything but a democratic politics, Purdy says, is to exclude, to perpetuate injustice, and to oppress.

However, Purdy goes on, if we abandon an idealized nature,

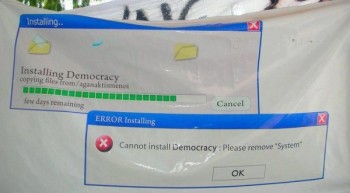

if we embrace not just the Anthropocene condition but also the insight—if we accept that there is no boundary between nature and human action and that nature therefore cannot provide a boundary around contestation—we may have the basis of a democratic future. It will be democratic in the double sense of thoroughly politicizing nature’s future and recognizing the imperative of political equality among the people who will together create that future.

Whether a thoroughly politicized nature can aid us in creating a just future is an experiential question. We’ll prove or disprove it by political action rather than by theologizing about nature. (Yet every time we’ve attempted to discount a religious or theological view, it has returned in surprising force. Should we abandon theology for activism?)

In attempting to outline what a future democratic politics of nature might look like, Purdy offers the Food Movement as a kind of Exhibit A. Though the movement can be reduced to or parodied as privileged (mostly white) humans indulging in artisanal cheeses and wines at prices no one outside the 10% can afford, it marks the beginnings of much more, and

includes a number of elements that might be generalized to help shape the politics of the Anthropocene. First, it recognizes that the aesthetically and culturally significant aspects of environmental politics are not restricted to romantic nature but are also implicated in economic and policy areas long regarded as purely utilitarian. For example, a beautiful landscape worth preserving so that people can encounter it need not be pristine: it could be an agricultural landscape—preserved under easements or helped along by a network of farmers markets and farm-to-table organizations—whose cultural contribution is that people can work on it.

One problem with past policy is a fragmentation that separates and de-couples landscape from economy. The land is not merely a neutral resource. “The most credible food politics would combine an aesthetic attention to landscape with a concern for power and justice in the work of food production … [and] “ask what kinds of landscapes agriculture should make and what kinds of human lives should be possible there, so that the food movement’s interest in landscape and work is not restricted to showpiece enclaves for the wealthy.”

This blog and many of its concerns come under critique when Purdy remarks

It is too easy to say that, in the Anthropocene, we have to get used to change—a bromide that comes most readily to those with some control over the changes they confront—when the real problem is precisely how to build politics that can make the next set of changes more nearly a product of democratic intent than they currently seem destined to be.

I write from a decided position of privilege. So, of course, does Purdy. He and I both belong to that tiny minority on the planet “with some control over the changes they confront.” And if you’re literate and have time to read blogs and access to the technology where they appear, so do you. Though some days it may not feel like it, we have the luxury to question why and imagine how and even manifest what next.

I write from a decided position of privilege. So, of course, does Purdy. He and I both belong to that tiny minority on the planet “with some control over the changes they confront.” And if you’re literate and have time to read blogs and access to the technology where they appear, so do you. Though some days it may not feel like it, we have the luxury to question why and imagine how and even manifest what next.

Here on this blog I contemplate and explore a minority practice and belief, and try to make sense of my experience and the historical period I find myself in. To blog at all is to write from time left after making a living. How many of us have that? Besides, if everyone talks, who listens? Blogs ideally create dialog. But often a blogger like me can be guilty of doing more talking and less listening. (It’s ideally a balance rather than a binary opposition.)

Purdy notes in that last excerpt that he spies a definite trend or direction. He hopes “the next set of changes [will be] more nearly a product of democratic intent than they currently seem destined to be.” And he ends with a curious bow that seems to evoke much he has taken pains to empty of force.

Even that thought, however, is a reminder that this is only a fighting chance, part of a fighting future. The politics of the Anthropocene will be either democratic or horrible. That alternative is no guarantee that a democratic Anthropocene would be decorous, pleasant, or admirable, but only that it would be a shared effort to shape our more-than-human future with human hands.

Is there no alternative between democratic or horrible? Isn’t our own era an example of both? And what is that “more-than-human” future he says that we will shape with our own less than godlike human hands?!

/|\ /|\ /|\

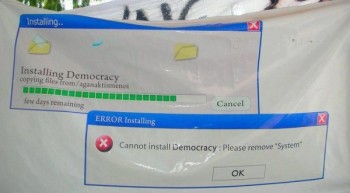

IMAGES: Purdy; ostriches; “in wilderness” quotation; installing democracy; add new post.

*Lummis, C Douglas. Radical Democracy. Cornell University Press, 1997.

[I happened on Lummis years ago and have been grateful ever since. A professor of cultural studies at Tsuda University in Japan, Lummis, who has spent much of life overseas, ably critiques Western trends and politics from the vantage point of an inside-outsider. Most of his work has been published in Japan, and often in Japanese — and hence he’s not as widely known in the West as he deserves.]

In a 15 Feb 2008 post “Taboo Your Words,” Eliezer Yudkowsky writes:

The illusion of unity across religions can be dispelled by making the term “God” taboo, and asking them to say what it is they believe in; or making the word “faith” taboo, and asking them why they believe it … When you find yourself in philosophical difficulties, the first line of defense is not to define your problematic terms, but to see whether you can think without using those terms at all. Or any of their short synonyms. And be careful not to let yourself invent a new word to use instead. Describe outward observables and interior mechanisms; don’t use a single handle, whatever that handle may be.

There’s a truly breathtaking number of assumptions I could examine in this short excerpt. To name only a few: that any unity across religions is or isn’t an “illusion”; that any such unity hinges on either “God” or belief; that the only acceptable kinds of evidence are “outward observables and interior mechanisms”; that arguments or philosophical defenses establish truth; and that language, let alone philosophical discussion, is even possible without “handles,” which is what all words are. (In the beginning was the Word …)

But let’s set those issues aside — because we can. I recommend taking on this challenge for what it can teach you. Take an hour and get down in words what it is you actually believe, and why. Whatever else is calling to you online, including this blog, can wait.

For Druids, the word to make temporarily taboo is definitely “nature.”

After all, we use it as shorthand for an enormous range of referents: an object of our reverence; a source of our metaphors; the set of patterns, relationships and movements of energies that we claim accounts for all life, including the workings of human consciousness; the antithesis to human excess and imbalance, often symbolized by urban blight; a kind of deity or pantheon of deities; a characteristic quality that is the opposite of the word “artificial”; everything that exists, including those human activities that produce counter-currents and eddies in its ever-flowing stream; an impersonal force or being, and so on.

So I’ll take on Yudkowsky’s challenge: what is it that I believe, and why?

I believe that to be alive is a chance, if I take it, to be part of something vastly larger than my own body, emotions, and thoughts (or if I’ve learned any empathy, possibly also the bodies, emotions and thoughts of people I care about). These things have their place, but they are not all.

I believe this because when I pay attention to the plants and animals, air, sky, water and the whole wordless living environment in and around me, I am lifted out of the small circle of my personal concerns and into a deeper kinship I want to celebrate. I discover this sense of connection and relationship is itself celebration. Because of these experiences, I believe further that if I focus only on my own body, emotions, and thoughts, I’ve missed most of my life and its possibilities. Ecstasy is ec-stasis, standing outside. Ecstatic experiences lift us out of the narrowness of the life that advertisers tell us should be our focus and into a world of beauty and harmony and wisdom.

I believe likewise that the physicality of this world is something to learn deeply from. The most physical experiences we know, eating and hurting, being ill and making love, dying and being born, all root us in our bodies and focus our attention on now. They take us to wordless places where we know beyond language. Even to witness these things can be a great teacher.

I believe in other worlds than this one because, like all of us, I’ve been in them, in dream, reverie, imagination and memory, to name only a few altered states. I believe that our ability to live and love and die and return to many worlds is what keeps us sane, and that the truly insane are those who insist this world is the only one, that imagination is dangerous, metaphor is diabolical, dream is delusion, memory is mistaken, and love? — love, they tell us, is merely a matter of chemical responses.

I believe that humans, like all things, are souls and have bodies, not the other way around — that the whole universe is animate, that all things vibrate and pulse with energy, as science is just beginning to discover, and that we are (or can be) at home everywhere because we are a part of all that is.

I believe these things because human consciousness, like the human body, is marvelously equipped for living in this universe, because of all its amazing capacities that we can see working themselves out for bad and good in headlines and history. In art and music and literature, in the deceptions and clarities, cruelties and compassions we practice on ourselves and each other, we test and try out our power.

New York Times columnist Dana Jennings wins the first “Druid of the Day” award particularly for this portion of his column in yesterday’s (7/10/12) Times:

Scenes From the Meadowlandscape

Monet had his haystacks, Degas had his dancers, and I have the New Jersey Meadowlands from the window of my Midtown Direct train as I travel to and from Manhattan.

But what, it’s fair to ask, does squinting out at the Meadowlands each day have to do with art, with culture? Well, as a novelist and memoirist for more than 20 years, I like to think that if I stare hard enough — even from a speeding train — I can freeze and inhabit the suddenly roomy moment. Through the frame that is my train window I’m able to discern and delight in any number of hangable still lifes.

And the Meadowlands never disappoints, no matter what exhibition is up.

Its shifting weave of light, color and texture hone and enchant the eye. The sure and subtle muscle of the Hackensack River is sometimes just a blue mirror, but when riled and roiled by wind and rain it becomes home to slate-gray runes. The scruff, scrub and brush are prickly and persistent, just like certain denizens of New Jersey. And the brontosaurus bridges, their concrete stumps thumped into the swamp, idly look down on it all.

For his focus, intentionality and the requisite quietness to see, and then — just as important — turn the results of that seeing into a window, an access point for others who read his column to do the same “noticing” in their own lives, Jennings earns my commendation as “Druid of the Day.” This seemed like a good series to launch, to help remind myself as well as my readers of ways we can be more attentive to beauty around us, particularly unexpected instances — free, a gift if we only notice them — and receive their transformative power.

City or country, it doesn’t matter: we can be witnesses of natural power and beauty, and learn what they may have to teach us, anywhere — including Manhattan, and from the window of the Midtown Direct train. These are no less — or more — “Druidic” than any other spots on the planet.

Know others who deserve recognition as “D of the D”? Please send them along to me and I’ll write them up and include an acknowledgement to you in the citation. Thanks in advance.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Here are Yin and Yang, our two rhododendrons — a single red flower grows on the pink bush in the foreground, with a branch of the red bush showing in the background. Plant envy? Unfortunately the red bush doesn’t have a single pink flower, or the image would be complete. In a month they’ll be back to their usually ungainly woody scraggly selves, with no hint of the glory they present each May. Is the aftermath the only time we appreciate what we had — when it’s finally gone?

Here are Yin and Yang, our two rhododendrons — a single red flower grows on the pink bush in the foreground, with a branch of the red bush showing in the background. Plant envy? Unfortunately the red bush doesn’t have a single pink flower, or the image would be complete. In a month they’ll be back to their usually ungainly woody scraggly selves, with no hint of the glory they present each May. Is the aftermath the only time we appreciate what we had — when it’s finally gone?

The aftermath is the consequences, the results, the outcome. But we never hear of a “foremath,” whatever it is that stands before the event, the “math” — literally the “mowing” in Old English.

Most of our yard is the typical rural patch of grass, which given half a chance will turn to sumac, crabgrass, chicory, dandelions and even slender saplings inside six months. In the few years that we’ve owned the house, we’ve let whole quadrants go uncut for a season. Sometimes it’s from pure practical laziness — we’ve no one to impress, after all, and no condo association to yelp at us — and it saves gas and time, until we get around to putting in more of the permanent plantings that won’t require cutting. Until then, we’re getting the lay of the land, seeing how soil and drainage and sun all work together (our three blueberry bushes, visible in the background in the second photo, thrive on the edge of our septic leachfield), and which local species lay claim first when we give them a chance to grow and spread. The moles that love our damp soil also tunnel madly when we leave off mowing for the summer. We think of it as natural aeration for the earth.

Most of our yard is the typical rural patch of grass, which given half a chance will turn to sumac, crabgrass, chicory, dandelions and even slender saplings inside six months. In the few years that we’ve owned the house, we’ve let whole quadrants go uncut for a season. Sometimes it’s from pure practical laziness — we’ve no one to impress, after all, and no condo association to yelp at us — and it saves gas and time, until we get around to putting in more of the permanent plantings that won’t require cutting. Until then, we’re getting the lay of the land, seeing how soil and drainage and sun all work together (our three blueberry bushes, visible in the background in the second photo, thrive on the edge of our septic leachfield), and which local species lay claim first when we give them a chance to grow and spread. The moles that love our damp soil also tunnel madly when we leave off mowing for the summer. We think of it as natural aeration for the earth.

The northwest corner, shown here, shaded by the house itself for part of the day, yields wild strawberries if we mow carefully, first exposing the low-lying plants to sun, and then waiting while the berries ripen. Patches of wildflowers emerge — common weeds, if you’re indifferent to the gift of color that comes unlabored-for. I like to hold off till they go to seed, helping to ensure they’ll come back another year, and making peace with the spirits of plant species that — if you can believe the Findhorn experience and the lore of many traditional cultures — we all live with and persistently ignore to our own loss.

This year we’ve “reclaimed” most of the lawn for grass, as we expand the cultivated portion with raised beds and berry patches. But I remind myself that we haven’t left any of it “undeveloped” — the unconscious arrogance of the word, applied to land and whole countries, suggests nature has no intention or capacity of its own for doing just fine without us. Who hasn’t seen an old driveway or parking lot reverting to green? Roots break up the asphalt remarkably fast, and every crack harbors a few shoots of green that enlarge the botanical beach-head for their fellows. Tarmac and concrete, macadam and bitumen are not native species.

And what would any of us do, after all, without such natural events like the routine infection of our guts by millions of beneficial bacteria to help with digestion? A glance at the entry for gut flora at Wikipedia reveals remarkable things:

Gut flora consist of microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of animals and is the largest reservoir of human flora. In this context, gut is synonymous with intestinal, and flora with microbiota and microflora.

The human body, consisting of about 10 trillion cells, carries about ten times as many microorganisms in the intestines. The metabolic activities performed by these bacteria resemble those of an organ, leading some to liken gut bacteria to a “forgotten” organ. It is estimated that these gut flora have around 100 times as many genes in aggregate as there are in the human genome.

Bacteria make up most of the flora in the colon and up to 60% of the dry mass of feces. Somewhere between 300 and 1000 different species live in the gut, with most estimates at about 500. However, it is probable that 99% of the bacteria come from about 30 or 40 species. Fungi and protozoa also make up a part of the gut flora, but little is known about their activities.

Research suggests that the relationship between gut flora and humans is not merely commensal (a non-harmful coexistence), but rather a mutualistic relationship. Though people can survive without gut flora, the microorganisms perform a host of useful functions, such as fermenting unused energy substrates, training the immune system, preventing growth of harmful, pathogenic bacteria, regulating the development of the gut, producing vitamins for the host (biotin and vitamin K), and producing hormones to direct the host to store fats.

Such marvels typically set off echoes in me, and because much of my training and predilection is linguistic in nature, the echoes often run to poems. A moment’s work with that marvelous magician’s familiar Google brings me the lines of “Blind” by Harry Kemp:

The Spring blew trumpets of color;

Her Green sang in my brain–

I hear a blind man groping

“Tap-tap” with his cane;

I pitied him in his blindness;

But can I boast, “I see”?

Perhaps there walks a spirit

Close by, who pities me–

A spirit who hears me tapping

The five-sensed cane of mind

Amid such unsensed glories

That I am worse than blind.

Isn’t this all a piece of both the worst and the best in us? We can be fatally short-sighted and blind, but we can also imagine our own blindness, see our own finitude — and move beyond it to a previously unimagined larger world.

Of course, the challenges that humans have faced throughout our history frequently outpace our existing institutions, wisdom and capacity to take effective action. That’s one workable definition of “crisis,” after all. And the compulsions and sufferings of a crisis often catalyze the formation of just those institutions, wisdoms and capacities. (They also fail to do this painfully often, as we’ve learned to our cost.)

Of course, the challenges that humans have faced throughout our history frequently outpace our existing institutions, wisdom and capacity to take effective action. That’s one workable definition of “crisis,” after all. And the compulsions and sufferings of a crisis often catalyze the formation of just those institutions, wisdoms and capacities. (They also fail to do this painfully often, as we’ve learned to our cost.) Thus, Purdy points out, “Even wilderness, once the very definition of naturalness, is now a statutory category in U.S. public-lands law.” The Sierra Club still markets this (outdated, in Purdy’s perspective) view as one of its touchstones: “In wilderness is the salvation of the world.” (By way of Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, paraphrasing Thoreau’s Walden; Thoreau actually wrote preservation.)

Thus, Purdy points out, “Even wilderness, once the very definition of naturalness, is now a statutory category in U.S. public-lands law.” The Sierra Club still markets this (outdated, in Purdy’s perspective) view as one of its touchstones: “In wilderness is the salvation of the world.” (By way of Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, paraphrasing Thoreau’s Walden; Thoreau actually wrote preservation.) But throughout human history, Purdy notes, various and successively changing ideals of nature have underpinned diverse economic and political arrangements that always consistently disenfranchise a designated fraction of humans. Whether slaves, minorities, women, aboriginal peoples, immigrants, certain racial or ethnic groups, someone always gets the short end of the stick from these idealizations of “nature.” To hold the natural world to anything but a democratic politics, Purdy says, is to exclude, to perpetuate injustice, and to oppress.

But throughout human history, Purdy notes, various and successively changing ideals of nature have underpinned diverse economic and political arrangements that always consistently disenfranchise a designated fraction of humans. Whether slaves, minorities, women, aboriginal peoples, immigrants, certain racial or ethnic groups, someone always gets the short end of the stick from these idealizations of “nature.” To hold the natural world to anything but a democratic politics, Purdy says, is to exclude, to perpetuate injustice, and to oppress. I write from a decided position of privilege. So, of course, does Purdy. He and I both belong to that tiny minority on the planet “with some control over the changes they confront.” And if you’re literate and have time to read blogs and access to the technology where they appear, so do you. Though some days it may not feel like it, we have the luxury to question why and imagine how and even manifest what next.

I write from a decided position of privilege. So, of course, does Purdy. He and I both belong to that tiny minority on the planet “with some control over the changes they confront.” And if you’re literate and have time to read blogs and access to the technology where they appear, so do you. Though some days it may not feel like it, we have the luxury to question why and imagine how and even manifest what next.