Archive for the ‘spiritual tools’ Category

[Earth Mysteries 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7]

The second principle or law Greer examines is the Law of Flow. Before I get to it, a word about spiritual or natural laws. In my experience, we tend to think of laws, if we think of them at all, in their human variety. I break a law every time I drive over the speed limit, and most of us have broken this or some other human law more than once in our lives. We may or may not get caught and penalized by the human institutions we’ve set up to enforce the laws we’ve established, though the majority of human laws also have some common sense built in. Driving too fast, for example, can lead to its own inherent penalties, like accidents, and besides, it wastes gas.

But spiritual or natural law can’t be “broken,” any more than the law of gravity or inertia can be “broken.” Other higher laws may come into play which subsume lower ones, and essentially transform them, but that’s a different thing. A spiritual law exists as an observation of how reality tends to work, not as an arbitrary human agreement or compromise like the legal drinking age, or monogamy, or sales tax. Another way to say it: real laws or natural patterns are what make existence possible. We can’t veto the Law of Flow, or vote it down, or amend it, just because it’s inconvenient or annoying or makes anyone’s life easier or more difficult. There are, thank God, no high-powered lawyers or special-interest groups lobbying to change reality — not that they’d succeed. Properly understood, spiritual or natural law provides a guide for how to live harmoniously with life, rather than in stress, conflict or tension with it. How do I know this? The way any of us do: I’ve learned it the hard way, and seen it work the easy way — and both of these in my life and in others’ lives. Once it clicks and I “get” it, it’s more and more a no-brainer. Until then, my life seems to conspire to make everything as tough and painful as possible. Afterwards, it’s remarkable how much more smoothly things can go. Funny how that works.

But spiritual or natural law can’t be “broken,” any more than the law of gravity or inertia can be “broken.” Other higher laws may come into play which subsume lower ones, and essentially transform them, but that’s a different thing. A spiritual law exists as an observation of how reality tends to work, not as an arbitrary human agreement or compromise like the legal drinking age, or monogamy, or sales tax. Another way to say it: real laws or natural patterns are what make existence possible. We can’t veto the Law of Flow, or vote it down, or amend it, just because it’s inconvenient or annoying or makes anyone’s life easier or more difficult. There are, thank God, no high-powered lawyers or special-interest groups lobbying to change reality — not that they’d succeed. Properly understood, spiritual or natural law provides a guide for how to live harmoniously with life, rather than in stress, conflict or tension with it. How do I know this? The way any of us do: I’ve learned it the hard way, and seen it work the easy way — and both of these in my life and in others’ lives. Once it clicks and I “get” it, it’s more and more a no-brainer. Until then, my life seems to conspire to make everything as tough and painful as possible. Afterwards, it’s remarkable how much more smoothly things can go. Funny how that works.

OK, so on to the Law of Flow:

“Everything that exists is created and sustained by flows of matter, energy and information that come from the whole system to which it belongs and return to that whole system. Participating in these flows, without interfering with them, brings health and wholeness; blocking them, in an attempt to turn flows into accumulations, brings suffering and disruption to the whole system and its parts.”*

“Participating in these flows, without interfering with them,” can be a life-long quest. Lots of folks have pieces of this principle, and some of the more easily-marketed ones are available at slickly-designed websites and at New Age workshops happening near you. But note that the goal is not to accumulate wealth beyond the wildest dreams of avarice. (As Greer points out, if the so-called “Law of Attraction” really worked as advertized, the whole planet would be a single immense palace of pleasure and ease. Though who would wait on us hand and foot, wash our clothes, make our high-priced toys, or grow and cook our food, remains unclear.) Flow means drawing from system, contributing to it, and passing along its energy. “Pay it forward” wouldn’t be out of place here.

If all this sounds faintly Socialist, well, remember that as Stephen Colbert remarked, “Reality has well-known liberal bias.” It means sharing, like most of us were taught as toddlers — probably shortly after we first discovered the power and seduction of “mine!” But it could just as easily and accurately be claimed that reality has a conservative bias. After all, these are not new principles, but age-old patterns and tendencies and natural dynamics, firmly in place for eons before humans happened on the scene. To know them, and cooperate with them, is in a certain sense the ultimate conservative act. The natural world moves toward equilibrium. Anything out of balance, anything extreme, is moved back into harmony with the larger system. The flows that sustain us also shape us and link us to the system. The system is self-repairing, like the human body, and ultimately fixes itself, or attempts to, unless too much damage has occurred.

Ignorance of this law lies behind various fatuous political and economic proposals now afloat in Europe and America. Of course, what’s necessary and what’s politically possible are running further and further apart these days, and will bring their own correction and rebalancing. We just may not like it very much, until we change course and “go with the flow.” That doesn’t mean passivity, or doing it because “everybody else is doing it.” Going with the flow in the stupid sense means ignoring the current and letting ourselves be swept over the waterfall. Going with the flow in the smart sense means watching and learning from the flow, using the current to generate electricity, or mill our grain, while relying on the nature of water to buoy us up, using the flow to help carry us toward our destination. Flow is not static but dynamic, the same force that not only sustains the system, but always find the easier, quicker, optimum path: if one is not available, flow carves a new one. The Grand Canyon is flow at work over time, as are the shapes of our bodies, the curve of a bird’s wing, the curl of waves, the whorls of a seashell, the spiral arms of galaxies, the pulse of the blood in our veins. Flow is the “zone” most of us have experienced at some point, that energy state where we are balanced and in tune, able to create more easily and smoothly than at other times. Hours pass, and they seem like minutes. Praised be flow forever!

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: river.

*Greer, John Michael. Mystery Teachings from the Living Earth. Weiser, 2012.

Normally I steer clear of posts that border on the political, because they accomplish little except to harden opinions and positions, and sharpen arguments, without leading to a solution. But I make an exception in this post, for reasons I hope will become clear.

Normally I steer clear of posts that border on the political, because they accomplish little except to harden opinions and positions, and sharpen arguments, without leading to a solution. But I make an exception in this post, for reasons I hope will become clear.

Especially in difficult times like these, we rely for perspective and direction on the supposed Wise Ones of our world, so it behooves them to be more cautious and informed in their public statements than this article by Tim Worstall in the U.K.’s Telegraph of May 16, 2012. The article byline for the author identifies him as “Senior Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute in London, and one of the global experts on the metal scandium, one of the rare earths,” so you’d think he’d exercise more care in an international forum like this newspaper. Here are his opening words, remarkable for their flippancy, misrepresentation and ignorance:

Apparently something terrible happens when we get to peak oil. I’ve never really quite understood the argument myself, but when we’ve used half of all the oil then civilisation collapses or something. I’m not sure why this should happen: we don’t start starving when there’s only half a loaf of bread left. But I am assured that something awful does happen.

That oil fields do get pumped out is obviously true – and also that you can have a good guess at when the ones we’re currently pumping will run out. The part I don’t get is the catastrophe. Some people seem to think that “peak oil” is when we can’t actually pump out a higher amount: that if we’ve got 70 million barrels a day, then that’s the most we can ever have, 70 million a day. Which is also called a disaster. Apparently this means that demand will move ahead of supply, which is simple sheer ignorance of the price system. There is no such thing as “supply” or “demand”. There is only either of them at a price. So, if there really is a limit on how fast we can pump the stuff up, the price will rise.

Worstall’s observations illustrate a confusion of realms, a common-enough misperception, and one we all make from time to time. In the case of a recognized expert, though, we expect greater wisdom and sense — he simply isn’t thinking things through. If you’re talking about the human economy of making brooms, say, or copies of DVDs of The Avengers, or oranges, or purebred Siamese cats, well and good. Then Worstall is right, and supply and demand will play out pretty much as he claims. Price is indeed the hinge between them. Even in extreme cases of demand, say for parts to an antique car that went out of production decades ago, you can probably find a craftsperson who will forge and finish them for you. Because they’re one-offs, they’ll cost you plenty. But if you want the parts badly enough, and you have the necessary cash or other acceptable medium of exchange, someone will oblige and supply your demand. That’s Econ. 101. It’s how modern economies are supposed to work. We get it.

But turn to the natural economy of the physical environment and a different picture emerges. The human and natural economies are NOT the same, and it’s dangerous to assume they are. In the natural economy, many materials aren’t renewable, and they’re simply not subject to supply and demand. A finite quantity exists, and when we use it up, there’s no more to be had, at any price.

Yes, we can grow more trees for wood, plant more fruits and vegetables for food. Many metals and other materials can be recycled, and so on. At least we’ve made a start on re-using and re-purposing. But oil and natural gas, to name just two resources, exist in finite qualities. Use more and we’ll run out sooner. Use less and they’ll last longer. Until we have replacements or other viable sources of energy, it’s only common sense to conserve and sip, rather than guzzle. It’s not like running out of milk and going down to the nearest convenience store, or ultimately putting another 10,000 cows into milk production. It’s rather as if I’m running out of air, trapped in a house-fire, or dragged underwater by a sinking ship. My demand for air may become extreme, but if the supply runs out, I eventually die. Life itself is finite, and no one has escaped its ending. No extensions for love or money. Demand for more hours or days has never obligated the universe to provide them, and no promise of payment or bribe suffices to keep our hearts beating a second longer. They stop.

In the case of oil and gas, unknown supplies no doubt still exist. Hydrofracking may prove helpful to buy us a little more time — or not. It may well go the way of ethanol, which for a while looked like the next sure thing. Yes, there’s petro-energy to be had, but if it costs more to produce than it’s worth, a different side of supply and demand switches on. For the geeks among us, that’s EROEI — energy returned on energy invested. We may have enough oil for 50 more years, or 75, or 100 or 200, but we will run out. At that point, demand won’t budge the simple physical fact of an exhausted resource. At too high a price, it’s not worth it to anyone to extract a few more gallons or cubic meters. As in the Monty Python parrot sketch, it’s kaput, used up, done, extinct, no more.

Unlike many peak-oil doomsayers, I’m willing to concede that down the road we may well devise a marvelous technological solution to our mammoth energy needs. But until we do, it’s deeply stupid to continue using more each year, rather than less, now that production has recently peaked, even as peak oil historians predicted it would, six decades ago. How high must the price of a barrel of oil rise, and how much must the economies and households and peoples of the world suffer, until that’s clear?

But good things will emerge from this crisis, too. They may not be what we want, but as the Stones (almost) said, “we just might find we get what we need” in the moment. And there’s material for future posts.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: buffalo shortage

Here are Yin and Yang, our two rhododendrons — a single red flower grows on the pink bush in the foreground, with a branch of the red bush showing in the background. Plant envy? Unfortunately the red bush doesn’t have a single pink flower, or the image would be complete. In a month they’ll be back to their usually ungainly woody scraggly selves, with no hint of the glory they present each May. Is the aftermath the only time we appreciate what we had — when it’s finally gone?

Here are Yin and Yang, our two rhododendrons — a single red flower grows on the pink bush in the foreground, with a branch of the red bush showing in the background. Plant envy? Unfortunately the red bush doesn’t have a single pink flower, or the image would be complete. In a month they’ll be back to their usually ungainly woody scraggly selves, with no hint of the glory they present each May. Is the aftermath the only time we appreciate what we had — when it’s finally gone?

The aftermath is the consequences, the results, the outcome. But we never hear of a “foremath,” whatever it is that stands before the event, the “math” — literally the “mowing” in Old English.

Most of our yard is the typical rural patch of grass, which given half a chance will turn to sumac, crabgrass, chicory, dandelions and even slender saplings inside six months. In the few years that we’ve owned the house, we’ve let whole quadrants go uncut for a season. Sometimes it’s from pure practical laziness — we’ve no one to impress, after all, and no condo association to yelp at us — and it saves gas and time, until we get around to putting in more of the permanent plantings that won’t require cutting. Until then, we’re getting the lay of the land, seeing how soil and drainage and sun all work together (our three blueberry bushes, visible in the background in the second photo, thrive on the edge of our septic leachfield), and which local species lay claim first when we give them a chance to grow and spread. The moles that love our damp soil also tunnel madly when we leave off mowing for the summer. We think of it as natural aeration for the earth.

Most of our yard is the typical rural patch of grass, which given half a chance will turn to sumac, crabgrass, chicory, dandelions and even slender saplings inside six months. In the few years that we’ve owned the house, we’ve let whole quadrants go uncut for a season. Sometimes it’s from pure practical laziness — we’ve no one to impress, after all, and no condo association to yelp at us — and it saves gas and time, until we get around to putting in more of the permanent plantings that won’t require cutting. Until then, we’re getting the lay of the land, seeing how soil and drainage and sun all work together (our three blueberry bushes, visible in the background in the second photo, thrive on the edge of our septic leachfield), and which local species lay claim first when we give them a chance to grow and spread. The moles that love our damp soil also tunnel madly when we leave off mowing for the summer. We think of it as natural aeration for the earth.

The northwest corner, shown here, shaded by the house itself for part of the day, yields wild strawberries if we mow carefully, first exposing the low-lying plants to sun, and then waiting while the berries ripen. Patches of wildflowers emerge — common weeds, if you’re indifferent to the gift of color that comes unlabored-for. I like to hold off till they go to seed, helping to ensure they’ll come back another year, and making peace with the spirits of plant species that — if you can believe the Findhorn experience and the lore of many traditional cultures — we all live with and persistently ignore to our own loss.

This year we’ve “reclaimed” most of the lawn for grass, as we expand the cultivated portion with raised beds and berry patches. But I remind myself that we haven’t left any of it “undeveloped” — the unconscious arrogance of the word, applied to land and whole countries, suggests nature has no intention or capacity of its own for doing just fine without us. Who hasn’t seen an old driveway or parking lot reverting to green? Roots break up the asphalt remarkably fast, and every crack harbors a few shoots of green that enlarge the botanical beach-head for their fellows. Tarmac and concrete, macadam and bitumen are not native species.

And what would any of us do, after all, without such natural events like the routine infection of our guts by millions of beneficial bacteria to help with digestion? A glance at the entry for gut flora at Wikipedia reveals remarkable things:

Gut flora consist of microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of animals and is the largest reservoir of human flora. In this context, gut is synonymous with intestinal, and flora with microbiota and microflora.

The human body, consisting of about 10 trillion cells, carries about ten times as many microorganisms in the intestines. The metabolic activities performed by these bacteria resemble those of an organ, leading some to liken gut bacteria to a “forgotten” organ. It is estimated that these gut flora have around 100 times as many genes in aggregate as there are in the human genome.

Bacteria make up most of the flora in the colon and up to 60% of the dry mass of feces. Somewhere between 300 and 1000 different species live in the gut, with most estimates at about 500. However, it is probable that 99% of the bacteria come from about 30 or 40 species. Fungi and protozoa also make up a part of the gut flora, but little is known about their activities.

Research suggests that the relationship between gut flora and humans is not merely commensal (a non-harmful coexistence), but rather a mutualistic relationship. Though people can survive without gut flora, the microorganisms perform a host of useful functions, such as fermenting unused energy substrates, training the immune system, preventing growth of harmful, pathogenic bacteria, regulating the development of the gut, producing vitamins for the host (biotin and vitamin K), and producing hormones to direct the host to store fats.

Such marvels typically set off echoes in me, and because much of my training and predilection is linguistic in nature, the echoes often run to poems. A moment’s work with that marvelous magician’s familiar Google brings me the lines of “Blind” by Harry Kemp:

The Spring blew trumpets of color;

Her Green sang in my brain–

I hear a blind man groping

“Tap-tap” with his cane;

I pitied him in his blindness;

But can I boast, “I see”?

Perhaps there walks a spirit

Close by, who pities me–

A spirit who hears me tapping

The five-sensed cane of mind

Amid such unsensed glories

That I am worse than blind.

Isn’t this all a piece of both the worst and the best in us? We can be fatally short-sighted and blind, but we can also imagine our own blindness, see our own finitude — and move beyond it to a previously unimagined larger world.

Urban Dictionary (check it out if you haven’t yet visited it) obliges with this definition of “sick nasty”: “This word is to be used when no other word can be used to describe the cool factor, greatness, or overwhelming emotion of something. However, the something is neither sick, nor nasty. The combination of the words sick and nasty provide a higher connotation of coolness then even the words tight or wicked can provide. It is kind of ghetto.”

Since I’m going for the literal rather than the metaphoric, I’ll bypass the ghetto, and the slang meanings of “ill,” too, and head straight for “body in misery.” (It’s worth considering what connection coolness has with physical sickness, because when you’re in it, it’s distinctly not cool at all.)

Food poisoning can leave you half alive, no longer trusting your organs and bones. My wife and I had been out of state to attend our niece’s high school graduation, and bad food choices dropped me into my own private third level of hell (that’s for the gluttons, which seems appropriate). I won’t gross you out with gastrointestinal details: enough to say that the aftermath left me with aching joints, residual fever and chills, a nasty headache, and no desire ever to eat again. To add insult to injury, we’d scheduled medical check-ups back home the next day. Sometimes you feel rotten enough that a doctor is the last person you want to see. And on top of that, he insisted it was time I had another digital rectal exam, part of the follow-through since my prostate surgery. Necessary, maybe, but oh so evil.

OK, enough self-pity. You get the idea. This is a blog, after all, that’s supposed to provide plenty of buck (see the 5/18/12 entry). No time to slack off now.

What illness can offer, besides a physical cleansing and rebalancing (we get sick when something’s out of whack, off kilter, messed up), is clarity, humility and gratitude. At least that’s what I often get (when the worst of the symptoms have subsided), if I’m lucky.

Clarity first. Flat on your back, you’ve got time to reflect. If you’re not unconscious or delirious, reasonably free of pain, and cable is unavailable, you’re thrown back on yourself. Time to make friends with the body, to coax it back to health if you can. This marvelous machine of flesh now sits in the garage, lies in drydock, has gone off-line. Time to adjust the timing belt, scrape off the barnacles, repair the hull, and reboot. You get all kinds of ideas, some of which might even be useful. You get to watch your thoughts spin like a Tibetan prayer wheel, only more gooey. And through and above and below and within it all, you realize there are limits. You get reacquainted with the fact that you will die. Your time here is limited. You can’t have it all, do it all, own it all. You get your turn, and then it’s the next person’s. What you do with your life is your gift to yourself.

Clarity first. Flat on your back, you’ve got time to reflect. If you’re not unconscious or delirious, reasonably free of pain, and cable is unavailable, you’re thrown back on yourself. Time to make friends with the body, to coax it back to health if you can. This marvelous machine of flesh now sits in the garage, lies in drydock, has gone off-line. Time to adjust the timing belt, scrape off the barnacles, repair the hull, and reboot. You get all kinds of ideas, some of which might even be useful. You get to watch your thoughts spin like a Tibetan prayer wheel, only more gooey. And through and above and below and within it all, you realize there are limits. You get reacquainted with the fact that you will die. Your time here is limited. You can’t have it all, do it all, own it all. You get your turn, and then it’s the next person’s. What you do with your life is your gift to yourself.

And yes — I can get didactic and preachy, kinda. Bear with me.

The humility part is good. You have to rely on others. When your body’s in meltdown, somebody else has to bring the drugs and the drinks, or you don’t get them. You can’t get up without the world playing spin the bottle with your brain, or chills racking you, or legs turning to water. That backrub to ease the crying vertebrae, the cool washcloth so welcome on hot skin, the light turned off because it hurts your eyes, the curtains drawn for the same reason, the soup that’s the only thing you can keep down — all of these are gifts that either others give you, or you don’t get them. They’re out of your control. Your minute-to-minute life is discomfort, interrupted by the kindness of someone caring for you.

Which brings you to gratitude. You certainly have time for it. If you have to be sick, at least there’s some good that comes of it — later, if not right away. As you start to feel better, you recall how you took so much for granted. You resolve to try to do better. Maybe the first stirrings of belief in immortality begin here, with recovery from illness. You’re aren’t dying after all. This too shall pass. You rise again. You will live to enjoy life again.

/|\ /|\ /|\

prayer wheel

Druid teaching, both historically and in contemporary versions, has often been expressed in triads — groups of three objects, perceptions or principles that share a link or common quality that brings them together. An example (with “check” meaning “stop” or “restrain”): “There are three things not easy to check: a cataract in full spate, an arrow from a bow, and a rash tongue.” Some of the best preserved are in Welsh, and have been collected in the Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Triads of the Island of Britain*, pronounced roughly tree-oyth un-iss pruh-dine). The form makes them easier to remember, and memorization and mastery of triads were very likely part of Druidic training. Composing new ones offers a kind of pleasure similar to writing haiku — capturing an insight in condensed form. (One of my favorite haiku, since I’m on the subject:

Druid teaching, both historically and in contemporary versions, has often been expressed in triads — groups of three objects, perceptions or principles that share a link or common quality that brings them together. An example (with “check” meaning “stop” or “restrain”): “There are three things not easy to check: a cataract in full spate, an arrow from a bow, and a rash tongue.” Some of the best preserved are in Welsh, and have been collected in the Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Triads of the Island of Britain*, pronounced roughly tree-oyth un-iss pruh-dine). The form makes them easier to remember, and memorization and mastery of triads were very likely part of Druidic training. Composing new ones offers a kind of pleasure similar to writing haiku — capturing an insight in condensed form. (One of my favorite haiku, since I’m on the subject:

Don’t worry, spiders —

I keep house

casually.

— Kobayashi Issa**, 1763-1827/translated by Robert Hass)

A great and often unrecognized triad appears in the Bible in Matthew 7:7 (an appropriately mystical-sounding number!). The 2008 edition of the New International Version renders it like this: “Keep asking, and it will be given to you. Keep searching, and you will find. Keep knocking, and the door will be opened for you.”

Apart from the obvious exhortation to persevere, there is much of value here. Are all three actions parallel or equivalent? To my mind they differ in important ways. Asking is a verbal and intellectual act. It involves thought and language. Searching, or seeking, may often be emotional — a longing for something missing, a lack or gap sensed in the soul. Knocking is concrete, physical: a hand strikes a door. All three may be necessary to locate and uncover what we desire. None of the three is raised above the other two in importance. All of them matter; all of them may be required.

And what are we to make of this exhortation to keep trying? Many cite scripture as if belief itself were sufficient, when verses like this one make it clear that’s not always true. Spiritual achievement, like every other kind, demands effort. Little is handed to us without diligence on our part.

And what are we to make of this exhortation to keep trying? Many cite scripture as if belief itself were sufficient, when verses like this one make it clear that’s not always true. Spiritual achievement, like every other kind, demands effort. Little is handed to us without diligence on our part.

And though the three modes of investigation or inquiry aren’t apparently ranked, it’s long seemed to me that asking is lowest. If you’ve got nothing else, try a simple petition. It calls to mind a child asking for a treat or permission, or a beggar on a street-corner. The other two modes require more of us — actual labor, either of a quest, or of knocking on a door (and who knows how long it took to find?).

It’s possible to see the three as a progression, too — a guide to action. First, ask in order to find out where to start, at least, if you lack other guidance. With that hint, begin the quest, seeking and searching until you start “getting warm.” Once you actually locate what you’re looking for — the finding after the seeking — it’s time to knock, to try out the quest physically, get the body involved in manifesting the result of the search. Without this vital third component of the quest, the “find” may never actually make it into life where we live it every day.

Sometimes the knocking is initiated “from the other side” In Revelations, the Galilean master says, “I stand at the door and knock.” Here the key seems to be to pay attention and to open when you hear a response to all your seeking and searching. The universe isn’t deaf, though it answers in its own time, not ours. The Wise have said that the door of soul opens inward. No point in shoving up against it, or pushing and then waiting for it to give, if it doesn’t swing that way …

/|\ /|\ /|\

*The standard edition of the Welsh triads for several decades is the one shown in the illustration by Rachel Bromwitch, now in its 3rd edition. The earliest Welsh triads appearing in writing date from the 13th century.

**Issa (a pen name which means “cup of tea”) composed more than 20,000 haiku. You can read many of them conveniently gathered here.

book cover; door image.

Ah, Fifth Month, you’ve arrived. In addition to providing striking images like this one, the May holiday of Beltane on or around May 1st is one of the four great fire festivals of the Celtic world and of revival Paganism. Along with Imbolc, Lunasa and Samhain, Beltane endures in many guises. The Beltane Fire Society of Edinburgh, Scotland has made its annual celebration a significant cultural event, with hundreds of participants and upwards of 10,000 spectators. Many communities celebrate May Day and its traditions like the Maypole and dancing (Morris Dancing in the U.K.). More generally, cultures worldwide have put the burgeoning of life in May — November if you live Down Under — into ritual form.

Ah, Fifth Month, you’ve arrived. In addition to providing striking images like this one, the May holiday of Beltane on or around May 1st is one of the four great fire festivals of the Celtic world and of revival Paganism. Along with Imbolc, Lunasa and Samhain, Beltane endures in many guises. The Beltane Fire Society of Edinburgh, Scotland has made its annual celebration a significant cultural event, with hundreds of participants and upwards of 10,000 spectators. Many communities celebrate May Day and its traditions like the Maypole and dancing (Morris Dancing in the U.K.). More generally, cultures worldwide have put the burgeoning of life in May — November if you live Down Under — into ritual form.

I’m partial to the month for several reasons, not least because my mother, brother and I were all born in May. It stands far enough away from other months with major holidays observed in North America to keep its own identity. No Thanksgiving-Christmas slalom to blunt the onset of winter with cheer and feasting and family gatherings. May greens and blossoms and flourishes happily on its own. It embraces college graduations and weddings (though it can’t compete with June for the latter). It’s finally safe here in VT to plant a garden in another week or two, with the last frosts retreating until September. At the school where I teach, students manage to keep Beltaine events alive even if they pass on other Revival or Pagan holidays.

I’m partial to the month for several reasons, not least because my mother, brother and I were all born in May. It stands far enough away from other months with major holidays observed in North America to keep its own identity. No Thanksgiving-Christmas slalom to blunt the onset of winter with cheer and feasting and family gatherings. May greens and blossoms and flourishes happily on its own. It embraces college graduations and weddings (though it can’t compete with June for the latter). It’s finally safe here in VT to plant a garden in another week or two, with the last frosts retreating until September. At the school where I teach, students manage to keep Beltaine events alive even if they pass on other Revival or Pagan holidays.

The day’s associations with fertility appear in Arthurian lore with stories of Queen Guinevere’s riding out on May Day, or going a-Maying. In Collier’s painting above, the landscape hasn’t yet burst into full green, but the figures nearest Guinevere wear green, particularly the monk-like one at her bridle, who leads her horse. Guinevere’s affair with Lancelot eroticized everything around her — greened it in every sense of the word. Tennyson in his Idylls of the King says:

The day’s associations with fertility appear in Arthurian lore with stories of Queen Guinevere’s riding out on May Day, or going a-Maying. In Collier’s painting above, the landscape hasn’t yet burst into full green, but the figures nearest Guinevere wear green, particularly the monk-like one at her bridle, who leads her horse. Guinevere’s affair with Lancelot eroticized everything around her — greened it in every sense of the word. Tennyson in his Idylls of the King says:

For thus it chanced one morn when all the court,

Green-suited, but with plumes that mocked the may,

Had been, their wont, a-maying and returned,

That Modred still in green, all ear and eye,

Climbed to the high top of the garden-wall

To spy some secret scandal if he might …

Of course, there are other far more subtle and insightful readings of the story, ones which have mythic power in illuminating perennial human challenges of relationship and energy. But what is it about green that runs so deep in European culture as an ambivalent color in its representation of force?

Of course, there are other far more subtle and insightful readings of the story, ones which have mythic power in illuminating perennial human challenges of relationship and energy. But what is it about green that runs so deep in European culture as an ambivalent color in its representation of force?

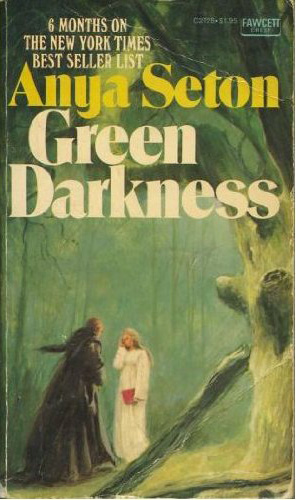

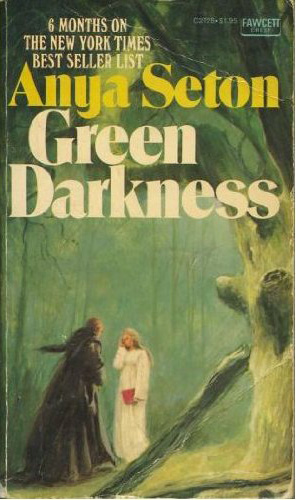

Anya Seton’s novel Green Darkness captures in its blend of Gothic secrecy, sexual obsession, reincarnation and the struggle toward psychic rebalancing the full spectrum of mixed-ness of green in both title and story. As well as the positive color of growth and life, it shows its alternate face in the greenness of envy, the eco-threat of “greenhouse effect,” the supernatural (and original) “green giant” in the famous medieval tale Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the novel and subsequent 1973 film Soylent Green, and the ghostly, sometimes greenish, light of decay hovering over swamps and graveyards that has occasioned numerous world-wide ghost stories, legends and folk-explanations.

(Wikipedia blandly scientificizes the phenomenon thus: “The oxidation of phosphine and methane, produced by organic decay, can cause photon emissions. Since phosphine spontaneously ignites on contact with the oxygen in air, only small quantities of it would be needed to ignite the much more abundant methane to create ephemeral fires.”) And most recently, “bad” greenness showed up during this year’s Earth Day last month, which apparently provoked fears in some quarters of the day as evil and Pagan, and a determination to fight the “Green Dragon” of the environmental movement as un-Christian and insidious and horrible and generally wicked. Never mind that stewardship of the earth, the impetus behind Earth Day, is a specifically Biblical imperative (the Sierra Club publishes a good resource illustrating this). Ah, May. Ah, silliness and wisdom and human-ness.

We could let a Celt and a poet have (almost) the last word. Dylan Thomas catches the ambivalence in his poem whose title is also the first line:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

The force that drives the water through the rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.

The hand that whirls the water in the pool

Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind

Hauls my shroud sail …

Yes, May is death and life both, as all seasons are. But something in the irrepressible-ness of May makes it particularly a “hinge month” in our year. The “green fuse” in us burns because it must in order for us to live at all, but our burning is our dying. OK, Dylan, we get it. Circle of life and all that. What the fearful seem to react to in May and Earth Day and things Pagan-seeming is the recognition that not everything is sweetness and light. The natural world, in spite of efforts of Disney and Company to the contrary, devours as well as births. Nature isn’t so much “red in tooth and claw” as it is green.

Yes, things bleed when we feed (or if you’re vegetarian, they’ll spill chlorophyll. Did you know peas apparently talk to each other?). And this lovely, appalling planet we live on is part of the deal. It’s what we do in the interim between the “green fuse” and the “dead end” that makes all the difference, the only difference there is to make. So here’s Seamus Heaney, another Celt and poet, who gives us one thing we can do about it: struggle to make sense, regardless of whether or not any exists to start with. In his poem “Digging,” he talks about writing, but it’s “about” our human striving in general that, for him, takes this particular form. It’s a poem of memory and meaning-making. We’re all digging as we go.

Digging

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; as snug as a gun.

Under my window a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade,

Just like his old man.

My grandfather could cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, digging down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mold, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

/|\ /|\ /|\

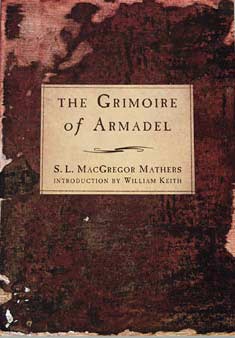

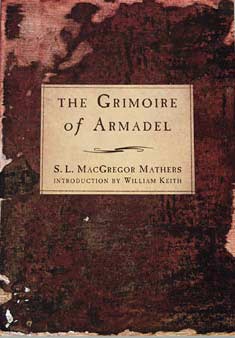

Beltane Fire Society image; Maibaum; John Maler Collier’s Queen Guinevere’s Maying; Soylent Green; Green Darkness; peat.

Go to Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

I speak for myself, of course. It’s all that any of us can do. But as I approach what is most deeply true for me, I find I can begin to speak true for others, too. Most of us have had such an experience, and it’s an instance of the deep connections between us that we often forget or discount. I’m adding this Part Two because the site stats say the earlier post on initiation continues to be popular.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Within us are secrets. Not because anyone hides some truths from us, but because we have not yet realized them. The truest initiations we experience seem ultimately to issue from this inner realm of consciousness where the secrets arise. Deeper than any ocean, our inner worlds are often completely unknown to us. “Man is ‘only’ an animal,” we hear. Sometimes that seems the deepest truth we can know. But animals also share in profound connections we have only begun to discover. We can’t escape quite so easily.

Our truest initiations issue from inside us. Sometimes these initiations come unsought. Or so we think. Maybe you go in to work on a day like any other, and yet you come home somehow different. Or you’re doing something physical that does not demand intellect and in that moment you realize a freedom or opening of consciousness. Sometimes it can arrive with a punch of dismay, particularly if you have closed yourself off from the changes on the move in your life. In its more dramatic forms initiation can bring with it a curious sense of vulnerability, or even brokenness — the brokenness of an egg that cracks as this new thing emerges, glistening, trembling. You are not the same, can never be the same again.

The German poet Rilke tries to catch something of this in his poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” He’d been blocking at writing the poems he desired, poems of greater depth and substance, instead of the often abstract work he’d composed until then, and his friend the sculptor Rodin sets him to studying animals. Rilke admires Rodin’s intensely physical forms and figures, and Rilke ends up writing about a classic figure of Apollo that is missing the head. Yet this headless torso still somehow looks at him, holds him with eyes that are not there. Initiation is both encounter, and its after-effects.

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

I may witness something that is simply not there for others, but nonetheless it is profoundly present for me. Or I see something that is not for the head to decipher, interpret, judge and comment on. There’s nothing there for the intellect to grasp. In the poem, the head of the sculpture of Apollo is missing, and yet it sees me, and I see or know things not available to my head. I feel the gaze of the sculpture. I encounter a god. Or just a piece of stone someone shaped long ago into a human figure, that somehow crystallizes everything in my life for me right now. Or both.

The sensation of initiation can be as intensely felt and as physical as sexuality, “that dark center where procreation flared.” It hits you in your center, where you attach to your flesh, a mortal blow from a sword or a gesture that never reaches you, but which still leaves you dizzy, bleeding or gasping for breath. Or it comes nothing like this, but like an echo of all these things which have somehow already happened to you, and you didn’t know it at the time — it somehow skipped right past you. But now you’re left to pick up the pieces of this thing that used to be your life.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

You feel Rilke’s discovery in those last lines*, the urgency, the knowledge arriving from nowhere we can track. I have to change, and I’ve already changed. I know something with my body, in my gut, that my head may have a thousand opinions about. I may try to talk myself out of it, but I must change. Or die in some way. A little death of something I can’t afford to have die. There is no place in my life that does not see me, that feeling rises that I can’t escape, and yet I must escape. It’s part of what drives some people to therapy. Sometimes we fight change until our last breath, and it takes everything from us. Or we change without knowing it, until someone who knows us says, “You’ve changed. There’s something different about you. I can’t put my finger on it,” or they freak at the changes and accuse us, as if we did it specifically to spite them. “You’re not the person you used to be,” meaning you’re no longer part of the old energy dynamic that helps them be who they are, and now they must change too. Initiation ripples outward. John Donne says, “No man is an island, entire of itself. Each man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Sometimes it’s my own initiation, sometime I’m feeling the ripples from somebody else’s. The earthquake is in the neighborhood, right down the street, in the next room, here — or across the ocean. But ripples in each case.

Sometimes we “catch” initiation from others, like a fire igniting. We encounter a shift in our awareness, and now we see something that was formerly obscure. It was there all along, nothing has changed, and yet … now we know something we didn’t before. This happens often enough in matters of love. The other person may have been with us all along, nothing has changed … and yet now we feel today something we didn’t feel yesterday. We know it as surely as we know our bones. We can feel the shift under our skin. The inner door is open. Do we walk through?

Go to Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Mitchell, Stephen, trans. The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke (English and German edition). Vintage, 1989.

Sometimes you have experiences that just don’t fit. They’re orphans, and like orphans, too often they’re left to fend for themselves, so they end up on the street. Or else they’re stuck in a home by some well-meaning authority, where they may subsist uncomfortably for years in places where everyone else looks and acts and talks different. There may not be enough love to go around, either, and like Oliver in Dickens’ novel Oliver Twist, they’re reduced to pleading, “Please, sir, may I have some more?”

Monday night, before the hard freeze here (19 and windy) that threatened all the burgeoning flowers and trees, I offered up a prayer. I don’t usually pray in this way, but I found myself praying for all the wordless Rooted Ones busy putting out buds and leaves and new growth in response to the warm spell that caressed so much of the U.S. “I cry to the Powers,” I found myself saying. A little more love here, please. The great willow in our back yard has pale leafy fronds. The currants are budding. Crabgrass pushes up from dead mats of last year’s growth. The stems of bushes and the twigs of trees show reddish with sap. At the same time, I took stock in what I knew in some traditions about plant spirits, the personifications of energies that help individual species thrive.* Let the devas and plant guardians sort it out. Serve the larger balance — that sort of thing. Then the nudge to pray came, so I honored it. Everyone has a role to play. Then the goddess Skaði presented herself.

All this took place while I was driving down and then back home with my wife from an out-of-state trip to CT. Bookends to the day. We’d tried to be efficient with our driving and gas use, like the good Greenies that on occasion we actually are, and schedule several appointments for the same day. So we rose early, drove through welcome morning sun and glorious light to have a thermostat and brakes replaced on our car, get eye exams and prescriptions and glasses before a sale ended on April 1, drop off a gift at a friend’s house, and get to an admissions interview for a certificate program I’m interested in. (More about that as it progresses.)

We’d scheduled ourselves fairly loosely, but still the sequence of appointments mattered for times and distances to travel to the next stop. So when the car service that we’d been assured would take no more than two hours now promised to consume most of the day, we got a loaner car from the dealership, rescheduled and shuffled some of our meetings. Ah, modern life. Maybe it’s no more than imagination, but at such times recall of past lives makes horse-and-buggy days seem idyllic and stress-free by contrast. Back then we didn’t do so much because we simply couldn’t. Does being able to do more always mean we should?

So, Skaði.** Not to belabor you with too much detail: she’s a Scandinavian goddess of winter, hunting, mountains and skiing. A sort of northern Diana of the snows, an Artemis of the cold heights and crags. I’d run across her a few years ago, when I was doing some reading and meditation in Northern traditions. She loomed in my consciousness then, briefly. Frankly I found Bragi, the god of eloquence and poetry and patron of bards, much more to my taste. But there she was, for a short time.

I flashed on an image of Skaði then, and she seemed — and still seems to me — quite literally cold, implacable, uninterested in humans, remote, austere, elegant in the way ice formations and mountain snows and the Himalayas are elegant — and utterly forbidding. Not someone even slightly interested in exchange, in human interaction. Now here she was. If you’ve been pursued by any of the Shining Folk, whether the Morrigan or Thor, Jesus or Apollo, you know that often enough they choose you rather than the other way around. So you make do. You pay no attention. Or you can’t help it and now you have a patron deity. Or something in between. If you’re a bloody fool, you blab about it too much, insisting, and the nice men in white coats fit you for one too. Or maybe you and Thorazine become best friends. It’s at times like this that I’m glad of the comparative anonymity of this blog. I can be that bloody fool, up to a point, and the people who need to will pass me off as just another wacko blogger. And then this post will recede behind the others, and only one or two people will happen on it in another month or two. The gods are out there, and they’re in our heads, too. Both/and. So we deal with it. And I can step back to my normal life. Or not. I’ll keep you posted.

I flashed on an image of Skaði then, and she seemed — and still seems to me — quite literally cold, implacable, uninterested in humans, remote, austere, elegant in the way ice formations and mountain snows and the Himalayas are elegant — and utterly forbidding. Not someone even slightly interested in exchange, in human interaction. Now here she was. If you’ve been pursued by any of the Shining Folk, whether the Morrigan or Thor, Jesus or Apollo, you know that often enough they choose you rather than the other way around. So you make do. You pay no attention. Or you can’t help it and now you have a patron deity. Or something in between. If you’re a bloody fool, you blab about it too much, insisting, and the nice men in white coats fit you for one too. Or maybe you and Thorazine become best friends. It’s at times like this that I’m glad of the comparative anonymity of this blog. I can be that bloody fool, up to a point, and the people who need to will pass me off as just another wacko blogger. And then this post will recede behind the others, and only one or two people will happen on it in another month or two. The gods are out there, and they’re in our heads, too. Both/and. So we deal with it. And I can step back to my normal life. Or not. I’ll keep you posted.

So Skaði of the daunting demeanor wants something. I prayed to the Powers, almost in the Tolkien Valar = “Powers” sense — to anyone who was listening. Open door. Big mistake? I’m a Druid, but here’s the Northern Way inserting itself into my life. My call goes out, and Skaði picks up and we’re having this conversation in my head while I drive north on I-91 with my wife. I’ve gotten used to these kinds of things over time, as much as you can, which often isn’t so much. In a way I suppose it’s revenge — I used to laugh out loud at such accounts when I read them and shake my head at what were “obviously people’s mental projections.” Now I’ve got one saying if you want protection for your shrubbery (God help me, I’m also hearing the scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail at this point. The Knights of Ni: “Bring me a shrubbery!”), then do something for me. What? I said. A blog post, first, then a website shrine. So here’s the blog post first. I’ll provide the shrine link when I’ve set it up.

/|\ /|\ /|\

*If you’re interested in an excellent account of this, check out The Findhorn Garden, originally published in 1976. This Scottish community, established on a barren piece of land, “inexplicably” flourished with the help of conscious cooperation with nature spirits. It’s documented in photographs and interviews. There are several books with similar titles and later dates, also published by Findhorn Community.

**The ð in her name is the “th” sound in with. I’m slowly realizing that part of my fussing over words, the urge to get it right, the annoyance at others who seem not to care about linguistic details, can be transformed to a gift. So for me part of honoring Skaði is getting her name right.

Image: Skaði. I can’t draw or paint to save my life, so when I came across this stunning representation, a shiver slalomed down my back. Skaði’s footsteps, I guess I should say. This is in the spirit of my experience of the goddess.

“Only what is virgin can be fertile.” OK, Gods, now that you’ve dropped this lovely little impossibility in my lap this morning, what am I supposed to do with it? Yeah, I get that I write about these things, but where do I begin? “Each time coming to the screen, the keyboard, can be an opportunity” — I know that, too. But it doesn’t make it easier. Why don’t you try it for a change? Stop being all god-dy and stuff and try it from down here. Then you’ll see what it’s like.

OK, done? Fit of pique over now?

I never had much use for prayer. Too often it seems to consist either of telling God or the Gods what to do and how to do it (if you’re arrogant) or begging them for scraps (if they’ve got you afraid of them, on your knees for the worst reasons). But prayer as struggle, as communication, as connecting any way you can with what matters most — that I comprehend. Make of this desire to link an intention. A daily one, then hourly. Let if fill, if if needs to, with everything in the way of desire, and hand that back to the universe. Don’t worry about Who is listening. Your job is to tune in to the conversation each time, to pick it up again. And the funny thing is that once you stop worrying about who is listening, everything seems to be listening (and talking). Then the listening rubs off on you as well. And you finally shut up.

That’s the second half, often, of the prayer. To listen. Once the cycle starts, once the pump gets primed, it’s easier. You just have to invite and welcome who you want to talk with. Forget that little detail, and there can be lots of other conversations on the line. The fears and dreams of the whole culture. Advertisers get in your head, through repetition. (That’s why it’s best to limit TV viewing, or dispense with it altogether, if you can. Talk about prayer out of control. They start praying you.) They’ve got their product jingle and it’s not going away. Sometimes all you’ve got in turn is a divine product jingle. It may be a song, a poem, a cry of the heart. The three Orthodox Christian hermits of the great Russian novelist Tolstoy have their simple prayer to God: “We are three. You are three. Have mercy on us!” Over time, it fills them, empowers them. They become nothing other than the prayer. They’ve arrived at communion.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Equi-nox. Equal night and day. The year hanging, if only briefly, in the balance of energies. Spring, a coil of energy, poised. The earth dark and heavy, waiting, listening. The change in everything, the swell of the heart, the light growing. Thaw. The last of the ice on our pond finally yields to the steady warmth of the past weeks, to the 70-degree heat of Tuesday. The next day, Wednesday, my wife sees salamanders bobbing at the surface. Walk closer, and they scatter and dive, rippling the water.

/|\ /|\ /|\

I once heard a Protestant clergywoman say to an ecumenical assembly, “We all know there was no Virgin Birth. Mary was just an unwed, pregnant teenager, and God told her it was okay. That’ s the message we need to give girls today, that God loves them, and forget all this nonsense about a Virgin birth.” … I sat in a room full of Christians and thought, My God, they’re still at it, still trying to leach every bit of mystery out of this religion, still substituting the most trite language imaginable …

The job of any preacher, it seems to me, is not to dismiss the Annunciation because it doesn’t appeal to modern prejudices, but to remind congregations of why it might still be an important story (72-73).

So Kathleen Norris writes in her book Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith. She goes on to quote the Trappist monk, poet and writer Thomas Merton, who

describes the identity he seeks in contemplative prayer as a point vierge [a virgin point] at the center of his being, “a point untouched by illusion, a point of pure truth … which belongs entirely to God, which is inaccessible to the fantasies of our own mind or the brutalities of our own will. This little point … of absolute poverty,” he wrote, “is the pure glory of God in us” (74-5).

So if I need to, I pull away the God-language of another tradition and listen carefully “why it might still be an important story.” Not “Is it true or not?” or “How can anybody believe that?” But instead, why or how it still has something to tell me. Another kind of listening, this time to stories, to myths, our greatest stories, for what they still hold for us.

One of the purest pieces of wisdom I’ve heard concerns truth and lies. There are no lies, in one sense, because we all are telling the truth of our lives every minute. It may be a different truth than we asked for, or than others are expecting, but it’s pouring out of us nonetheless. Ask someone for the truth, and if they “lie,” their truth is that they’re afraid. That knowledge, that insight, may well be more important than the “truth” you thought you were looking for. “Perfect love casteth out fear,” says the Galilean. So it’s an opportunity for me to practice love, and take down a little bit of the pervasive fear that seems to spill out of lives today.

Norris arrives at her key insight in the chapter:

But it is in adolescence that the fully formed adult self begins to emerge, and if a person has been fortunate, allowed to develop at his or her own pace, this self is a liberating force, and it is virgin. That is, it is one-in-itself, better able to cope with peer pressure, as it can more readily measure what is true to one’s self, and what would violate it. Even adolescent self-absorption recedes as one’s capacity for the mystery of hospitality grows: it is only as one is at home in oneself that one may be truly hospitable to others–welcoming, but not overbearing, affably pliant but not subject to crass manipulation. This difficult balance is maintained only as one remains [or returns to being] virgin, cognizant of oneself as valuable, unique, and undiminishable at core (75).

/|\ /|\ /|\

This isn’t where I planned to go. Not sure whether it’s better. But the test for me is the sense of discovery, of arrival at something I didn’t know, didn’t understand in quite this way, until I finished writing. Writing as prayer. But to say this is a “prayer blog” doesn’t convey what I try to do here, or at least not to me, and I suspect not to many readers. A Druid prayer comes closer, it doesn’t carry as much of the baggage as the word “prayer” may carry for some readers, and for me. “I’m praying for you,” friends said when I went into surgery three years ago. And I bit my tongue to keep from replying, “Just shut up and listen. That will help both us a lot more.” So another way of understanding my blog: this is me, trying to shut up and listen. I talk too much in the process, but maybe the most important part of each post is the silence after it’s finished, the empty space after the words end.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Norris, Kathleen. Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith. New York: Riverhead Books, 1998.

Some teachings run you through their rituals.

Find your own way – individuals

know what works beyond the shown way:

try out drinking with the Ancestors.

Chat ‘em up — don’t merely greet ‘em;

such rites are chummy: do more than meet ’em.

(Spend your weekends with a mummy?)

But I like drinking with my Ancestors.

Another round of pints and glasses

will have us falling on our asses.

Leave off ritual when they’re calling —

you’ll be drinking with your Ancestors.

By and with the spirits near us —

“Don’t invoke us if you fear us” —

good advice: if you lose focus

though you’re drinking with your Ancestors,

in the morning you’ll be uncertain

if you just dreamed or drew the curtain

on some world where it more than seemed

that you were drinking with your Ancestors.

Alcohol works its own magic,

and not all good – it’s downright tragic

if you’re just hung over from what could

have been you drinking with your Ancestors.

They come in all shapes, and in all sizes:

some are heroes, some no prizes

(they’re like us in all our guises).

Listen: they are singing, they are cussing,

they can advise us if we’re fussing

over where our lives might go

or put on a ghostly show.

We’re the upshot, on the down low.

We’re the payoff, crown and fruit

(we got their genetic trash, and loot),

we’re their future – “build to suit.”

So start drinking with your ancestors.

* * *

Ancestor “worship” is sometimes a misnomer, though not always — some cultures do in fact pray to, propitiate and appease the spirits of the ancestral dead in ways indistinguishable from worship. But others acknowledge what is simply fact — an awful lot (the simple fact that we’re here means our ancestors for the most part aren’t literally “an awful lot”) of people stand in line behind us. Their lives lead directly to our own. With the advent of photography it’s become possible to see images beyond the three- or four-generation remove that usually binds us to our immediate forebears. I’m lucky to have a Civil War photo of my great-great grandfather, taken when he was about my age, in his early fifties. In the way of generations past, he looks older than that, face seamed and thinned and worn.

The faces of our ancestral dead are often rightfully spooky. We carry their genetics, of course, and often enough a distant echo of their family traditions, rhythms, expectations, and stories in our own lives — a composite of “stuff,” of excellences and limitations, that can qualify as karma in its most literal sense: both the action and the results of doing. But more than that, in the peculiar way of images, the light frozen there on the photograph in patches of bright and dark is some of the purest magic we have. My great-great-grandfather James looks out toward some indeterminate distance — and in the moment of the photo, time — and that moment is now oddly immortal. Who knows if it was one of his better days? He posed for a photo, and no doubt had other things on his mind at the time, as we all do. We are rarely completely present for whatever we’re doing, instead always on to the next thing, or caught up in the past, wondering why that dog keeps barking somewhere in the background, wondering what’s for dinner, what tomorrow will bring, whether any of our hopes and ambitions and worries justify the energy we pour into them so recklessly.

And I sit here gazing at that photo, or summoning his image from what is now visual memory of the photo, as if I met him, which in some way I now have. Time stamps our lives onto our faces and here is his face. No Botox for him. Every line and crease is his from simply living. And around him in my imagination I can pose him with his spouse and children (among them my great-grandfather William) and parents, and so on, back as far — almost unimaginably far — as we are human. Fifty thousand years? Two hundred thousand? A million? Yes, by the time that strain reaches me it’s a ridiculously thin trickle. But then, if we look back far enough for the connection, it’s the same trickle, so we’re told, that flows in the veins of millions of others around us. If we can trust the work of evolutionary biologists and geneticists, a very large number of people alive on the planet today descend from a relative handful of ultimate ancestors. Which seems at first glance to fly in the face of our instinct and of simple mathematics, for that spreading tree of ancestors which, by the time it reaches my great-great-grandfather’s generation, includes thirty people directly responsible for my existence (two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents and sixteen great-great grandparents). Someone called evolution the “ultimate game of survivor.” And now I break off one line, stalling forever this one particular evolutionary parade, because my wife and I have no children.

The poem of mine that opened this entry, “Drinking with the Ancestors,” suggests we can indeed meet and take counsel with members of this immense throng through the exercise of inhibition-lowering and imagination-freeing imbibing of alcohol. Of course there are also visualization exercises and still other techniques that are suitably alcohol-free — more decorous and tame. Depending on who you want to talk to among your clan, you can have an experience as real as most face-to-face talks with people who have skin on. The difference between us in-carnate and ex-carnate folks is indeed the carne. No sudden dispensation of wisdom automatically accrues to us just because we croak. A living idiot becomes a dead idiot. Likewise a wise soul is wise, in or out of flesh.

It seems fitting to end with an experience of the ancestors. Not mine, this time — I keep such things close, because often when we experience them, they are for us alone, and retain their significance and power only if we do not diminish them by laying them out for others who may know nothing of our circumstances and experiences. Wisdom is not a majority vote. Even my wife and I may not share certain inner discoveries. We’ve both learned the hard way that some experiences are for ourselves alone. But it’s a judgment call. Some things I share.

So in my place I give you Mary Stewart’s Merlin, in her novel The Hollow Hills*, recounting his quest for Excalibur, and an ancestor dream-vision that slides into waking. The flavor of it captures one way such an ancestral encounter can go, the opposite end of the easy beery camaraderie that can issue from making the libations that welcome ancestral spirits to a festival or party, as in my poem. Note the transition to daytime consciousness, the thin edge of difference between dream and waking.

I said “Father? Sir?” but, as sometimes happens in dreams, I could make no sound. But he looked up. There were no eyes under the peak of the helmet. The hands that held the sword were the hands of a skeleton … He held the sword out to me. A voice that was not my father’s said, “Take it.” It was not a ghost’s voice, or the voice of bidding that comes with vision. I have heard these, and there is no blood in them; it is as if the wind breathed through an empty horn. This was a man’s voice, deep and abrupt and accustomed to command, with a rough edge to it, such as comes from anger, or sometimes from drunkenness; or sometimes, as now, from fatigue.

I tried to move, but I could not, any more than I could speak. I have never feared a spirit, but I feared this man. From the blank of shadow below the helmet came the voice again, grim, and with a faint amusement, that crept along my skin like the brush of a wolf’s pelt felt in the dark. My breath stopped and my skin shivered. He said, and I now clearly heard the weariness in the voice: “You need not fear me. Nor should you fear the sword. I am not your father, but you are my seed. Take it, Merlinus Ambrosius. You will find no rest until you do.”

I approached him. The fire had dwindled, and it was almost dark. I put my hands out for the sword and he reached to lay it across them … As the sword left his grip it fell, through his hands and through mine, and between us to the ground. I knelt, groping in the darkness, but my hand met nothing. I could feel his breath above me, warm as a living man’s, and his cloak brushed my cheek. I heard him say: “Find it. There is no one else who can find it.” Then my eyes were open and it was full noon, and the strawberry mare was nuzzling at me where I lay, with her mane brushing my face (226-7).

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Stewart, Mary. The Hollow Hills. New York: Fawcett Crest Books, 1974.

Yes, secrets can be dangerous. But live long enough and you notice that most things which may be dangerous under certain conditions are often for that very reason also potential sources of valuable insight and energy. Poisons can kill, but also cure. Light can disinfect, and also burn. Different societies almost instinctively identify and isolate their favorite different sources of energy as destructive or at the least unsettling, just as the physical body isolates a pathogen, and for much the same reason: self-preservation.

Yes, secrets can be dangerous. But live long enough and you notice that most things which may be dangerous under certain conditions are often for that very reason also potential sources of valuable insight and energy. Poisons can kill, but also cure. Light can disinfect, and also burn. Different societies almost instinctively identify and isolate their favorite different sources of energy as destructive or at the least unsettling, just as the physical body isolates a pathogen, and for much the same reason: self-preservation.

For many Americans and for our culture in general, sex is one great “unsettler.” We need only look at our history. Problems with appropriate sexual morality have dogged our culture for centuries, and show no signs of letting up, if the current gusts of contention around contraception, abortion, homosexuality and abstinence education mean anything at all. Wall up sexuality and let it out only on a short leash, if at all, our culture seems to say. Release it solely within the bonds of heterosexual monogamy. Then you may escape the worst of its dangerous, unsettling, even diabolical power. You can identify this particular cultural fixation by the attention that even minor sexual miss-steps command, surpassing murder and other far more actually destructive crimes. Let but part of a breast accidentally escape its covering on TV or in a video, even for a moment, and you’d think the end of the world had truly arrived.

a Mikvah -- ritual bath

Other cultures diagnose the situation differently and thus choose different energy sources to obsess about and wall up, or shroud in ritual and doctrine and taboo. For some, it’s ritual purity. At least some flavors of Judaism focus on this, with the mikvah or ritual bath, various prohibitions and restrictions around menstruation, skin diseases and other forms of impurity, and the importance of continuing the family along carefully recorded bloodlines. The first five Biblical books, from Genesis to Deuteronomy, list such practices and taboos in often minute detail.

The Bible also testifies, in some of its more well-known stories, to the fate of individuals like Jacob’s brother Esau, who married outside the family, and thus forfeited God’s blessings and promises that came with blood descent from their grandfather Abraham. And one need only consider Ishmael, son of Abraham but not of an approved female, who is driven out into the wilderness with his mother Hagar, a slave and not a Hebrew. This Jewish Biblical story accounts for the origins of the Muslims, descendants of Ishmael or Ismail. (The Qur’an, not surprisingly, preserves a different account.) The flare-ups of animosity and sometimes visceral hatred between Jews and Muslims thus originate quite literally in a family inheritance squabble, if we take these stories at their word.

If secrets have at their heart a source of potent energy and culture-shattering power, no wonder Americans in particular suspect them. We like to think we can domesticate everything and turn it to our purposes: name it, own it, market it, even cage it and sell tickets for tourists to see it in captivity, properly chastened by our mastery. But the numinosity of existence defies taming.

Such an oppositional stance of course almost guarantees conflict and misunderstanding and ongoing lack of harmony. But the experience of some human cultures tells us that we can learn to discern, respect and work with primordial forces that do not bow to human will and cleverness. (Likewise, Western and American culture have demonstrated that fatalism and passivity are not the only possible responses to disease, natural disasters, and so on.) Master and servant are not the only relations possible. For a culture that prizes equality, we are curiously indifferent to according respect to sex, divinity, mortality and change, consciousness and dream, creativity and intuition as forces beyond our control, but wonderfully amenable to cooperation and mutual benefit.

So how do secrets fit in here? The ultimate goals of both magical and spiritual work converge. As J. M. Greer characterizes it,

… the work that must be done is much the same–the aspirant has to wake up out of the obsession with purely material experience that blocks awareness of the inner life, resolve the inner conflicts and imbalances that split the self into fragments, and come into contact with the root of the self in the transcendent realms of being (Greer, John Michael. Inside a Magical Lodge, 98).

Of course, much magical and spiritual practice does not (and need not) habitually operate at this level — but it could. “By the simple fact of its secrecy, a secret forms a link between its keeper and the realities that the web does not include; a bridge to a space between worlds,” Greer notes. This space makes room for inner freedom, and so the effort of maintaining secrecy can pay surprising psychological dividends.

Keeping a secret requires keeping a continual watch over what one is saying and how one is saying it, but the process of keeping such a watch has effects that reach far beyond that of simply keeping something secret. Through this kind of constant background attention certain kinds of self-knowledge become not only possible but, in certain situations, inevitable. Furthermore, this same kind of attention can be directed to other areas of one’s life, extending the reach of conscious awareness into fields that are too often left to the more automatic levels of our minds … Used in this way, secrecy is a method of reshaping the self … (Greer, 116-117).

Thus, the actual content of the secret may be quite insignificant, a fact that baffles those who “uncover” secrets and then wonder what the fuss was all about. Is that all there is? they ask, usually missing another aspect of secrecy: “things can be made important–not simply made to look important, but actually made important–by being kept secret” (Greer, 118). The effort of maintaining secrecy and the discoveries that effort allows can mean that the supposed secrets themselves are often next to meaningless without that effort and discovery.

In this case, the danger of secrecy lies in what it reveals rather than what it conceals. Once we discover the often arbitrary and always incomplete nature of the web of communication (and the cultural standards based on that web), we perceive their limitations and ways to step beyond them. Here secrecy has

a protective function on several different levels. To challenge the core elements of the way a culture defines the world is to play with dynamite, after all. There’s almost always a risk that those who benefit from the status quo will respond to too forceful a challenge with ridicule, condemnation or violence. Secrecy helps prevent this from becoming a problem, partly by makng both the challenge and the challengers hard to locate, but also by making the threat look far smaller than it may actually be (Greer, 127).

Secrecy forms part of the “cauldron of transformation”* available to us all. Most of us balk at true freedom and change. We may have to relinquish comforting illusions — about ourselves and our lives and the priorities we have set for ourselves. So like a mouse I take the cheese from the trap and get caught by the head — I yield up the possibility of growth in consciousness in return for some comfort that seems — and is — easier, less demanding. All it costs is my life.

Secrecy forms part of the “cauldron of transformation”* available to us all. Most of us balk at true freedom and change. We may have to relinquish comforting illusions — about ourselves and our lives and the priorities we have set for ourselves. So like a mouse I take the cheese from the trap and get caught by the head — I yield up the possibility of growth in consciousness in return for some comfort that seems — and is — easier, less demanding. All it costs is my life.