Archive for the ‘Christianity’ Category

[Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3]

Midwinter greetings to you all! It’s sunny and bitter cold here in southern VT. The mourning doves and chickadees mobbing our feeder have fluffed themselves against the chill — the original down jackets — the indoor thermometer says 62, and my main task today, besides writing this post, is keeping our house warm and fussing over the woodstove like a brood hen sitting a nest of chicks. Hope you’re bundled and warm — or if you live on the summer side of the globe, you’re making the most of the sun and heat while it lasts.

/|\ /|\ /|\

The long and complex associations between a dominant religion like Christianity and minority faiths and practices within the dominant religious culture, like Druidry, won’t be my primary focus in this post. I’m more interested in personalities and practices anyway. It’s from spiritual innovators that any transformation of consciousness spreads, and that includes people like Jesus. Or as George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) quipped in his play Man and Superman, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” I’m asserting that in the best sense of the word, we can count Jesus among the “unreasonable” men and women we depend on for progress.

The long and complex associations between a dominant religion like Christianity and minority faiths and practices within the dominant religious culture, like Druidry, won’t be my primary focus in this post. I’m more interested in personalities and practices anyway. It’s from spiritual innovators that any transformation of consciousness spreads, and that includes people like Jesus. Or as George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) quipped in his play Man and Superman, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” I’m asserting that in the best sense of the word, we can count Jesus among the “unreasonable” men and women we depend on for progress.

Mostly reasonable people like me don’t make waves. Cop out? Maybe. If I chose to stand in the front lines of protests against practices like fracking, wrote blogs and letters decrying the bought votes and cronyism of specific members of Congress, targeted public figures with letter campaigns, founded and led a visible magical or spiritual group or movement, made headlines and provided a ready source of colorful sound-bites, I’d win my quarter-hour of fame, and probably an FBI or NSA file with my name on it.* Maybe it would make a difference. Maybe not. Material for an upcoming post.

Back to the main topic of Jesus and Druidry. As Philip Carr-Gomm notes in his book Druid Mysteries,

Although Christianity ostensibly superseded Druidry, in reality it contributed to its survival, and ultimately to its revival after more than a millennium of obscurity. It did this in at least four ways: it continued to make use of certain old sacred sites, such as holy wells; it adopted the festivals and the associated folklore of the pagan calendar; it recorded the tales of the Bards, which encoded the oral teachings of the Druids; and it allowed some of the old gods to live in the memory of the people by co-opting them into the Church as saints. That Christianity provided the vehicle for Druidry’s survival is ironic, since the Church quite clearly did not intend this to be the case (p. 31).

One somewhat obscure but intriguing survival is the Scots poet Sir Richard Holland’s Buke of the Howlat(e) (Book of the Owlet), dating from the 1450s. Holland’s satirical poem is peopled with birds standing in for humans, and it stars an unhappy owl which has traveled to the Pope (a peacock) to petition for an improved appearance.

One somewhat obscure but intriguing survival is the Scots poet Sir Richard Holland’s Buke of the Howlat(e) (Book of the Owlet), dating from the 1450s. Holland’s satirical poem is peopled with birds standing in for humans, and it stars an unhappy owl which has traveled to the Pope (a peacock) to petition for an improved appearance.

In the process of considering the owl’s request, the Pope orders a banquet, and among the entertainments during the feast is a “Ruke” (a rook or raven) in the stanza below, which represents the traditional satirical and mocking bard (named in the poem as Irish, but actually Scots Gaelic), deploying the power of verse to entertain, assert his rights, and reprimand the powerful. Thus, some two centuries before the start of the Druid Revival, Holland’s poem preserves memory of the old bardic tradition. Bear with my adaptation here of stanza 62 of Holland’s long poem. Here, the Rook gives a recitation in mock Gaelic, mixed with the Scots dialect** of the poem, demanding food and drink:

In the process of considering the owl’s request, the Pope orders a banquet, and among the entertainments during the feast is a “Ruke” (a rook or raven) in the stanza below, which represents the traditional satirical and mocking bard (named in the poem as Irish, but actually Scots Gaelic), deploying the power of verse to entertain, assert his rights, and reprimand the powerful. Thus, some two centuries before the start of the Druid Revival, Holland’s poem preserves memory of the old bardic tradition. Bear with my adaptation here of stanza 62 of Holland’s long poem. Here, the Rook gives a recitation in mock Gaelic, mixed with the Scots dialect** of the poem, demanding food and drink:

So comes the Rook with a cry, and a rough verse:

A bard out of Ireland with beannachaidh Dhe [God’s blessings (on the house)]

Said, “An cluinn thu guth, a dhuine dhroch, olaidh mise deoch.

Can’t you hear a word, evil man? I can take a drink.

Reach her+ a piece of the roast, or she+ shall tear thee.

[+the speaker’s soul — a feminine noun in Gaelic]

Mise mac Muire/Macmuire (plus indecipherable words)

I am the son of Mary/I am Macmuire.

Set her [it] down. Give her drink. What the devil ails you?

O’ Diarmaid, O’ Donnell, O’ Dougherty Black,

There are Ireland’s kings of the Irishry,

O’ Conallan (?), O’ Conachar, O’ Gregor Mac Craine.

The seanachaid [storyteller], the clarsach [harp],

The ben shean [old woman], the balach [young lad],

The crechaire [plunderer], the corach [champion],

She+ knows them every one.”

[+again, the soul of the speaker]

If you can for a moment overlook the explicit Protestant mockery of the Papacy (the Pope as a Peacock, after all), here, then, is an early Renaissance indication that the Bardic tradition was still recalled and recognized widely enough to work in a poem. Holland’s poem is itself a satire, and in it, the bard demands food and drink as his right as a professional, shows off his knowledge of famous names, and generally makes himself at home, both satirizing and being satirized in Holland’s depiction of bardic arrogance. (For in the following stanza, he’s kicked offstage by two court fools, who then spend another stanza quarreling between themselves.)

Thus, when the first Druid Revivalists began in the 1600s to search for the relics and survivals and outlying remains of Druidry to pair up with what they knew Classical authors had said about the Druids, things like Holland’s poem were among the shards and fragments they worked with. I’ve written (here, here and here) about the tales from the Mabinogion which, as Carr-Gomm points out above, preserve much Druid lore, passed down in story form and preserved by Christian monastics long after the oral teachings (and teachers) apparently passed from the scene. OK, .

More about Revival Druidry, the Revivalists, and Druidic survivals, coming soon.

[Part 2 here.]

/|\ /|\ /|\

*It’s likely such a file already exists anyway: I lived and worked for a year in the People’s Republic of China, I had to be fingerprinted and cleared by the Dept. of State for a month-long teaching job in South Korea (a requirement of my S. Korea employer, not the U.S.) a couple of summers ago, and I practice not just one but two minority religions. If you’re reading this, O Agents of Paranoia, give yourselves a coffee break — nothing much continues to happen here.

**Below is Holland’s original stanza 62 from his Buke of the Howlate. With the help of a dated commentary on Google Books, and the online Dictionary of the Scots Language, I’ve worked on a rough translation/adaptation. If you know the poem (or know Scots), corrections are welcome!

Sae come the Ruke with a rerd, and a rane roch,

A bard owt of Irland with ‘Banachadee!’,

Said, ‘Gluntow guk dynyd dach hala mischy doch,

Raike here a rug of the rost, or so sall ryive the.

Mich macmory ach mach mometir moch loch,

Set here doune! Gif here drink! Quhat Dele alis the?

O Deremyne, O Donnall, O Dochardy droch

Thir ar his Irland kingis of the Irischerye,

O Knewlyn, O Conochor, O Gregre Makgrane,

The Schenachy, the Clarschach,

The Ben schene, the Ballach,

The Crekery, the Corach,

Scho kennis thaim ilk ane.

Carr-Gomm, Philip. Druid Mysteries: Ancient Wisdom for the 21st Century. London: Rider, 2002.

Diebler, Arthur. Holland’s Buke of the Houlate, published from the Bannatyne Ms, with Studies in the Plot, Age and Structure of the Poem. Chemnitz, 1897. Google Books edition, pp. 23-24.

Dictionary of the Scots Language.

Images: G B Shaw; rook; Laing edition of Buke of the Howlat cover.

The passing last month of Olivia Durdin-Robertson, author, painter, and priestess of Isis, was remarkably non-reported in the American press. The London Times (preview only) and Telegraph, and the Irish Times, however, all carried extensive obituaries. Colorful and delightfully eccentric, and co-founder with her late brother Lawrence of the international Fellowship of Isis in 1976, Robertson inspired many in a rediscovery of the feminine divine. Her writings, art, liturgies, rituals and personal example helped give a form to a widespread longing to experience the Goddess.

The passing last month of Olivia Durdin-Robertson, author, painter, and priestess of Isis, was remarkably non-reported in the American press. The London Times (preview only) and Telegraph, and the Irish Times, however, all carried extensive obituaries. Colorful and delightfully eccentric, and co-founder with her late brother Lawrence of the international Fellowship of Isis in 1976, Robertson inspired many in a rediscovery of the feminine divine. Her writings, art, liturgies, rituals and personal example helped give a form to a widespread longing to experience the Goddess.

Robertson was a member of the Irish landed gentry, and the family’s splendid Huntington Castle in County Carlow became under her influence a devotional center and extended series of shrines to the Goddess.

Robertson was a member of the Irish landed gentry, and the family’s splendid Huntington Castle in County Carlow became under her influence a devotional center and extended series of shrines to the Goddess.

I’m writing about Robertson not only because her life and work deserve to be known, but also for more personal reasons. As I’ve tried with varying success to record (Goddess and Human, Of Orders and Freedoms, Messing with Gods, Potest Dea-A Dream Vision), the Goddess is alive and on the move, even in my life. I say “even” because many trends often seem to pop up, flourish and fade before I even discover their existence. And I can be remarkably obtuse even when spirit knocks on the door.

I’m writing about Robertson not only because her life and work deserve to be known, but also for more personal reasons. As I’ve tried with varying success to record (Goddess and Human, Of Orders and Freedoms, Messing with Gods, Potest Dea-A Dream Vision), the Goddess is alive and on the move, even in my life. I say “even” because many trends often seem to pop up, flourish and fade before I even discover their existence. And I can be remarkably obtuse even when spirit knocks on the door.

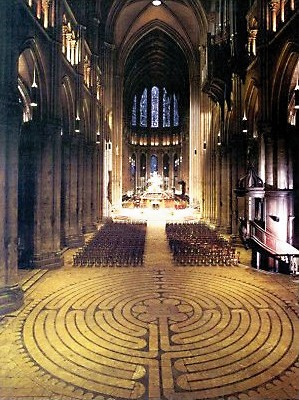

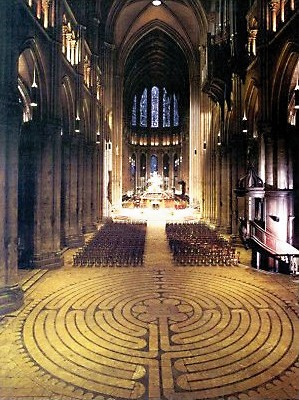

But the Goddess, through Her grace, is no mere trend. Will we look back at the present as another period of renewed veneration for Her, similar to the century or so of inspiration behind the construction of over 100 glorious Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals dedicated to the Virgin Mary in medieval Europe? (The most famous is Chartres, which many know both for the cathedral and for its labyrinth.* The best website is in French, worth visiting for its images even if you don’t know the language. On the horizontal menu, click on “La Cathedral” and then on “Panoramiques 360” — if you have sufficient bandwidth, the virtual tour is well worth your while.)

The most recent appearance of the Goddess (or a goddess — She/They may figure it all out someday) in my life is a series of meditation experiences this October over the span of a week. Isis called to me. The nature of the call wasn’t completely clear, and I also didn’t pay adequate attention. Goddesses aren’t really my thing, I might say, in an arrogant ignorance I intermittently see the extent of. As if the divine in any of its forms is something to dismiss as a matter of personal taste. But I have two color images of Isis I printed from the web (though they’re in a jumble of a side devotional area I haven’t finished ordering and dedicating), and I am continuing to work with meditation and vision to see what comes of it. I pulled a couple of her books** off my shelves, too — evidence she is a presence whether I attend to her well or not.

I mention this because now it feels more significant, in retrospect, with Robertson’s passing. Another reminder this life is finite, and that such opportunities, to the degree they manifest in time, do not wait forever, even if they may reoccur and reappear.

And if you can see from my admissions here how patient the divine can be with human slowness, indifference, ego, stubbornness and a few other choice weaknesses I’m probably missing at the moment, there’s really hope and encouragement for anyone at all.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: Olivia Durdin-Robertson; Huntington Castle; labyrinth;

*A good starting point for learning more about labyrinths is the extensive site of the Labyrinth Society.

**M. Isidora Forrest’s excellent Isis Magic (Llewellyn, 2001, recently out in a second edition), and Rosemary Clarke’s The Sacred Magic of Ancient Egypt (Llewellyn, 1st ed., 2nd printing, 2008).

We’ve read it, heard it, thought it, and many self-identify with it. It leaps faith boundaries; there are respectable atheists who lay claim to it. Meme, cop-out, canary in the mine, badge of honor, ticket to bad-ass-dom or philosopher status, tired PC label. High-mileage, time-to-change-the-tires, still-up-for-that-road-trip hippy van of the post-post-modern zeitgeist-fest that is for today what “finding yourself” was for a whole other lost generation not so long ago. You ask, and … there it comes, wait for it … “I’m spiritual, but not religious.”

Don’t misunderstand: I’m not mocking the impulse, just the frequent obliviousness of people who think it’s original with them. According to a Gallup poll from over a decade ago, 33% of Americans apply the SBNR label to themselves. I doubt that that percentage has dropped at all in the interim. If anything, it’s probably risen.

The phrase annoyed United Church of Christ pastor and author Lillian Daniel enough that she wrote a 2011 guest blog entry for The Huffington Post: “Spiritual But Not Religious? Please Stop Boring Me.” Responses to the post helped supply enough material that the original page grew into a book-length collection of essays —When “Spiritual But Not Religious” is Not Enough. [As a side note, only the first half of her book directly engages the topic of the title.]

The phrase annoyed United Church of Christ pastor and author Lillian Daniel enough that she wrote a 2011 guest blog entry for The Huffington Post: “Spiritual But Not Religious? Please Stop Boring Me.” Responses to the post helped supply enough material that the original page grew into a book-length collection of essays —When “Spiritual But Not Religious” is Not Enough. [As a side note, only the first half of her book directly engages the topic of the title.]

The “enoughness” of Daniel’s title refers to the importance of community, without which she feels a private spirituality can slide too easily into laziness and self-indulgence. Of course that can happen. Who holds people accountable for slipping into bad habits, if they seek to find their own truth, in their own way? [Turns out there ARE some “forces at large” who can keep us in line; for that, keep reading.] How do we avoid a kind of heedless religion of gratitude, if you live in the West and are comfortably middle- or upper-class? After all, that life can be pretty good much of the time: no starvation, war, oppression, plague and so on. How do we escape a superficial enjoyment of nature as the whole of our easy religion? (In particular, Daniel inveighs against the “Aren’t sunsets glorious?” crowd who think that their love of beauty is both original and that it “covers all sins.”)

Yes, there’s a Puritanical streak present in Daniel’s irritation (Puritanism defined by H. L. Mencken as “the haunting fear that someone somewhere is having a good time”). A fair portion of the SBNR’s may well come across as hedonist agnostics without a care (though I’ve yet to actually meet one), while the good people in congregations like Daniel’s engage each other in all their human imperfection, and are called to be better for it. But given the litany of ills the world faces, which any reflective person can see are attributable at least in part to the ongoing gluttony of first-world nations in their consumption of the planet’s resources, irritation is a perfectly reasonable response. Given the imperial overreach of those same nations in their attempt to bully and harangue the world so that their gullets remain as stuffed as possible, irritation might even be a good starting point for making an actual change — though Daniel goes nowhere near so far.

But there’s more of substance going on here, which Daniel is understandably reluctant to examine, since it cuts to the heart of her religion. Part of an “actual change” has already been going on for decades.

We can grasp one corner of the change in the words of now retired Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong. Spong notes in his Q & A for 11-7-2013 that those he terms the “non-religious” often are still spiritual:

We can grasp one corner of the change in the words of now retired Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong. Spong notes in his Q & A for 11-7-2013 that those he terms the “non-religious” often are still spiritual:

Lots of people who do go to church are “non-religious.” Lots of people who say they don’t believe in God are profoundly spiritual and searching people.

What I seek to describe with the phrase “the non-religious” are those for whom the traditional religious images have lost their meaning. There is no God above the sky, keeping record books, ready to answer your prayers and come to your aid. There is no tribal deity lurking over your nation or any other nation as a protective presence. There is no God who will free the Jews from Egyptian slavery; put an end to the Inquisition or stop the Holocaust. If these goals are to be accomplished, human beings with expanded consciousness will have to be the ones to accomplish them. This means that the category we call “religious” is too narrow and limited to work for us in the 21st century.

The question I seek to answer is that when we move beyond the religious symbols of the past, as I believe our whole culture has already done, do we move beyond the meaning those outdated symbols once captured for us, or is the meaning still there looking for a way to be newly understood and newly symbolized? The word “God” is a human symbol. I believe though that the word God stands for a reality that the word itself cannot fully embrace and that no human being can define. To worship God in our generation means not that we must move beyond God, but it does mean that we will have to move beyond all previous human definitions of God. So to be “non-religious” is just a way of saying that the religious symbols of the past have lost their meaning. That does not mean the search for God is over; it means the quest for new and different symbols has been engaged.

Some of what’s unintentionally ironic in Spong’s words here, intended to push against “Churchianity” and provoke mainstream Christians in its Pagan-like tolerance, is that many Christians would agree with him, and many Pagans and Druids in particular wouldn’t. For the polytheists among the latter, gods and goddesses are indeed real. Where Pagans and Druids do share common ground with Spong is in their conviction that there is a spiritual “reality that the word itself cannot fully embrace and that no human being can define.” But while it may be that some specifically Christian “religious symbols of the past have lost their meaning,” Pagan symbols feel new again. Paganism is growing because “the quest for new and different symbols has been engaged”; that’s what makes Neo-Paganism: so much is new. Talk to a Druid who’s encountered Cernunnos or Morrigan, who serves either as priestess or priest. Talk to a Wiccan who draws down the Moon.

Finally, if the posts on blogs like those on my sidebar of links are any indication, Pagans and Druids who may be solitaries and practice alone (as often out of necessity as out of choice) face their fair share of profound challenges in their spiritual practice that foster growth and unfolding, deeper awareness, and an enriched capacity to love. After all, Christian saints over nearly two millennia who retreated to hermitages and isolation from human others in order to deepen their spirituality also frequently found what they sought. It betrays a misunderstanding of spirituality to think we can’t practice alone. Fools and sages are pretty evenly distributed across the planet and throughout spiritual traditions. The sage I seek may live, not on the other side of the planet, but next door in the trailer, the one with the Chevy up on cement blocks in the front yard. The fool is often standing in front of me when I look in the mirror.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Daniel, Lillian. When “Spiritual But Not Religious” Is Not Enough. New York: Jericho Books, 2013.

Images: Lillian Daniel; John Shelby Spong.

Most spam to this site gets deleted without me ever seeing it. Some slips past the filters and I manually delete it after scanning it. The following piece that arrived earlier today felt like I could squeeze it for something bloggy:

“Cheap grace is the grace we bestow upon ourselves. Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession…Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate…When Christ calls someone, he bids them come and die.” – Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

We like things to be easy. We don’t want to have to think or commit too much to anything. We want to get the most reward for the least amount of effort. We expect it from our technology, our education, and from our God. “I went to church and I even put money in the offering, so we’re cool, right, God?” We did the minimum and we think that should be good enough. Yes, you’re still saved through grace; grace that is a free gift. But that grace is hollow, because you didn’t put yourself on the line for it. For years, our experience of church has been safe. Sit, stand, sing, bread, wine, Jesus loves you. Being a follower of Jesus is mainstream and acceptable. In most cases, we don’t risk anything by being a Christian. We proclaim a cotton candy gospel (that is, mostly sugar and air) and nobody gets stoned to death, crucified, or drawn and quartered. Do you see what I’m getting at? I’m not saying you have to defy the Roman Empire to validate your faith, but if you’re not willing to stand up for it, what is it really worth? What are we worth if we let intolerance and injustice rule over us without a fight?

The message intrigues me. (Learn wherever you can, I tell myself. Don’t turn away from a teacher just because you don’t like the color of her skin or the accent of his voice or the flavor of her wisdom. You might pass up something valuable.) It also spurred a set of responses.

One is how contrary to much preaching, but how common-sensical, it is: ya gotta work at anything worthwhile. Salvation in Christian terms is a gift, unearned, but this post tells a deeper truth. Salvation isn’t enough; it’s just the start. In eco-spiritual terms, Christians may get saved, but Druids get recycled.

The second probably arises out of the time of year. A good number of us are halfway into hibernation mode right now. Yes, we often want the easy path, because we’re lazy. Why expend energy pointlessly? Laziness makes good animal sense, up to a point. Devote your hours and muscles to acquiring food, finding a mate and — later — protecting your offspring. Anything else is likely not worth the effort. If you’re human, add in a few comforts you may have come to expect, if they don’t cost you or the planet too much trouble. Beyond that, it’s almost always diminishing returns for your efforts. OK, that’s one view.

Another is the universality of suffering, as Buddhists like to remind us. It’s not like Christians have any corner on resisting intolerance and injustice. To point out just one example, can anyone say Arab Spring? Any person can reach the tipping point of disgust with tyranny or suffering or despair and rise up to fight it. It need not be a specifically religious struggle at all — though it can be a profoundly spiritual act.

A fourth response (in case you’re counting): plenty of Pagans and Druids are also easy in their practices, just like the “cheap-grace” Christians in the spam above. And we can opt to let them enjoy a space and time where they may practice undisturbed. But others, depending on what part of the world they live in, may face considerable daily risk. Does that make them “better” Druids and Pagans — or Christians? Not necessarily. Maybe more careful, or stronger, or more committed. But these are character traits, present in some practitioners of all spiritualities and religions — and none.

A fifth response: the natural world calls Druids and Pagans to live consciously in it. We all die and are born, along with everything else. We’re compost after just a handful of decades. When the path of Druidry calls, it says wake up to the world we’re in right now. Whether or not it’s the only one, it’s this one, and our lives here, as long as we’re still breathing, are our answers every day. Figuring out what the questions are — well, that’s a task for a lifetime.

/|\ /|\ /|\

updated 22:15 EST 11 Feb 2013

“there is an altar to a different god,” wrote the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935). Perhaps that’s some explanation for the often mercurial quality of being this strange thing we call the self, ourselves. We can’t easily know who we are for the simple reason that (often, at least) we aren’t just one thing — we consist of multiple selves. We’re not individuals so much as hives of all our pasts buzzing around together. Whether you subscribe to the reality of past lives or see it as a possibly useful metaphor, we’re the sum of all we’ve ever been, and that’s a lot of being. And with past lives (or the often active impulses to make alternate lives for ourselves within this one through the dangerous but tempting choices we face) we’ve known ourselves as thieves and priests, saints and villains, women and men, victims and aggressors, ordinary and extraordinary. When we’ve finally done it all, we’re ready to graduate, as a fully-experienced self, a composite unified after much struggle and suffering and delight. All of us, then, are still in school, the school of self-making.

Doesn’t it just feel like that, some days at least?! Even only as a metaphor, it can offer potent insight. The Great Work or magnum opus of magic, seen from such a perspective, is nothing more or less than to integrate this cluster of selves, bang and drag and cajole all the fragments into some kind of coherence, and make of the whole a new thing fit for service, because that’s what we’re best at, once we’ve assembled ourselves into a truly workable self: to give back to life, to serve an ideal larger than our own momentary whims and wishes, and in the giving, to find — paradoxically — our best and deepest fulfillment. “He who loses himself will find it gain,” said a Wise One with a recent birthday we may have noticed. We all learn the hard way, for the most part, because it’s the most profound learning. Certainly it sticks in a way that most book learning alone does not.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Author, Episcopal priest and current professor Barbara Brown Taylor has written An Altar in the World, a splendid little book on simple, essential spiritual practices which anyone can begin right now. She writes from a refreshingly humble (close to the humus, the earth) Christian perspective, and a broad vision of spirituality pervades her words. Because of her insight and compassion, her awareness that we are whole beings — both spirits and bodies — because of the earthiness of her wisdom, and her refusal to set herself above any of her readers, she makes an excellent Druid of the Day. I hope I will always remember to apprentice myself gladly to whoever I can learn from. As the blurb on her website page for the book notes, “… no physical act is too earthbound to become a path to the divine.”

Author, Episcopal priest and current professor Barbara Brown Taylor has written An Altar in the World, a splendid little book on simple, essential spiritual practices which anyone can begin right now. She writes from a refreshingly humble (close to the humus, the earth) Christian perspective, and a broad vision of spirituality pervades her words. Because of her insight and compassion, her awareness that we are whole beings — both spirits and bodies — because of the earthiness of her wisdom, and her refusal to set herself above any of her readers, she makes an excellent Druid of the Day. I hope I will always remember to apprentice myself gladly to whoever I can learn from. As the blurb on her website page for the book notes, “… no physical act is too earthbound to become a path to the divine.”

Taylor brings a worthy antidote to the bad thinking and fear-mongering so widespread today. Here’s a sample:

… it is wisdom we need to live together in this world. Wisdom is not gained by knowing what is right. Wisdom is gained by practicing what is right, and noticing what happens when that practice succeeds and when it fails. Wise people do not have to be certain what they believe before they act. They are free to act, trusting that the practice itself will teach them what they need to know … If you are not sure what to believe about your neighbor’s faith, then the best way to find out is to practice eating supper together. Reason can only work with the experience available to it. Wisdom atrophies if it is not walked on a regular basis.

Such wisdom is far more than information. To gain it, you need more than a brain. You need a body that gets hungry, feels pain, thrills to pleasure, craves rest. This is your physical pass into the accumulated insight of all who have preceded you on this earth. To gain wisdom, you need flesh and blood, because wisdom involves bodies–and not just human bodies, but bird bodies, tree bodies, water bodies and celestial bodies. According to the Talmud, every blade of grass has its own angel bending over it whispering, “Grow, grow.” How does one learn to see and hear such angels? (14)

/|\ /|\ /|\

Taylor, Barbara Brown. An Altar in the World. New York: Harper One, 2009.

Since my wife and I are too cheap to spend money on cable, we get most of our programming through the internet. Vermont sometimes gets tagged in people’s minds as one of the hinterlands of the U.S., though in fact it’s scheduled to have ultra high-speed internet by 2013, billed as “fastest in the nation,” and VTel (Vermont Telephone) installers are actually ahead of schedule in some areas.

Since my wife and I are too cheap to spend money on cable, we get most of our programming through the internet. Vermont sometimes gets tagged in people’s minds as one of the hinterlands of the U.S., though in fact it’s scheduled to have ultra high-speed internet by 2013, billed as “fastest in the nation,” and VTel (Vermont Telephone) installers are actually ahead of schedule in some areas.

One result of our cable-free existence and frequent obliviousness to whatever is “trending now” is that we often discover programs toward the end of their initial run, or well after they’ve already gone to syndication or archive status. Hulu is one of our friends, so if you’ve already watched the Canadian series “Being Erica” and you’ve moved on to newer fare, this post may not be for you. It may be a case of BTDT (been there, done that). So my electronic alter ego here with his Druidry and opinions and evident desire to pry where it’s sometimes uncomfortable (but interesting!) to pry isn’t offended if you log off and go do your laundry, or at least surf onward toward something more engaging.

==PILOT EPISODE SPOILER ALERT==

If you’re still here, the show’s pilot episode does a good job of making the series premise clear. 32-year old Erica feels she’s over-educated (a Master’s degree) and under-fulfilled (single, and with a low-level telemarketing job). The pilot brings her to a low point — she wakes up in a hospital bed after an allergic reaction, and receives a brief visit from a Dr. Tom, who leaves her with a business card that reads “the only therapy you’ll ever need.” As Erica and the audience simultaneously discover, he’s able to send his patients back through time to deal with events in their pasts that they regret. Not to “fix” them in some facile way, but to learn more fully what they have yet to teach.

Vancouver Actor Erin Karpluk, who plays Erica, reveals a wonderful vulnerability and resilience, and she develops a daughter-father chemistry with Dr. Tom, played by veteran Michael Riley. There’s also a “Canadian” flavor to the series, by which I mean something mostly vaguely felt, but nevertheless detectable at certain moments: many episodes are less politically correct, more real, better scripted and more risk-taking than the typical formulaic and “safer” equivalent might end up being in the States. There’s been abortive planning to make both U.K. and U.S. versions.

So you know I just have to make a connection about now. Ah, and here it is, right on schedule. In my experience, the past is not some fixed thing, written into concrete forever, like one false step into a bog that draws you down and suffocates you. Instead, it depends for its whole existence on you, in your present, here and now, in these circumstances and with this awareness, to understand and explore it. Change your understanding of the past, and your past itself can change in almost any sense you care to claim. Not what the “facts” are, which is almost always the least important thing*, after all (peace to all those police procedural shows and their fans!), but how they matter and still shape you today. Just as history gets revised through time, as we gain new understandings and perspectives, so too do our own experiences, choices and destinies appear new or different to us as we change. That bully in grade school turns out to have helped us develop a thicker skin, or empathy — or an unacknowledged contempt for “trailer trash,” or a keen taste for revenge that dogs our heels to this day. Pick your blessing or poison.

The future is what is fixed, the track we’re still following, and reconfirming right now with our current habits, choices and focus — fixed, and set in stone — until we “change” our pasts by knowing and owning them more fully. Seen from this perspective, “fate” is undigested, rejected past that’s come back to haunt you. Healing comes not from literally changing “what happened” — possible only through repression or selective recall — but from squeezing out of each experience every last drop of wisdom and growth we can get from it. Yes: easier said than done. Much easier, often.

But if we find our pasts too painful to deal with, we’ll not only carry them around with us anyway, regardless, but miss out on their lessons as well. As therapist Rollo May said, “Either way, it hurts.” The point is not avoidance of pain, but growth. My past comes at me whispering (or shouting, depending), “Do something with your pain, Dude.” Revisiting and re-imaging the past may sound all New-Agey and Hallmarky, but if it’s one way among many to heal, why mock it or discount it, unless you love your pain more than anything else you have? “Yes, it may be pain, but it’s mine, my darling, my precious. Go dredge your own.” Gollum much?!

This present moment is the pivot, the hinge, the point of transformation, if I’m ever going to act on those New Year’s resolutions that now seem so distant. How many of them have I achieved? (In a December post, I confess to not making any, at least not big ones, partly for this reason.) Baby steps. What’s the smallest change I can make? That’s often the best starting point, because unlike the large resolution, I really can do the small stuff, and stick with it. And then build on it. Treat it all as experiment. Document it — write it down. (Oscar Wilde says one should keep a journal so that one always has something sensational to read.) My life as lab for change. Talk about a show.

Part of the appeal of “Erica,” of course, is watching somebody else go through this. Yet this isn’t merely a voyeuristic thrill so much as it is a provocation to reflect. A significant part of the interest of the series for me is that even Erica’s therapist Dr. Tom, while often truly guru-wise with her issues, isn’t God, or some perfected being. (We often really can see and understand others’ problems more clearly than our own. The challenge is not to abuse this insight, but make the most of it in the best way for our own specific circumstances.) He still has his struggles too — deep ones, as we come to discover, ones that come play a role in Erica’s therapy, to the dismay and growth of both of them.

And my response was “How right!” A perfect being would be a bit of a pain, and might have forgotten (or never known) what it’s like, this human gig. Jesus is never more useful and accessible than when he suffers humanly: when his friend Lazarus dies and he weeps, when he gets angry and physical at the money-changers for profaning the Temple, when the fig tree has no fruit because it’s not the season, and Jesus curses it anyway, when his friends ditch him to save themselves. This human thing, he gets it.

Incidentally, I’ve never understood the Christian obsession with sin. We’re all guilty and imperfect. Check. We’ve messed up. Check. But the point is that our pasts are our teachers. They help us grow. Our “sin” is what tempers and forges and perfects us in the end. Yes, it’s a long end. We’re all slow learners, those “special ed” kids, every one of us. A sequence of lives to learn and experience and grow and love in makes sense for this reason alone. For God or any Cosmic Cop to damn us to hell for “sin” cuts off the whole reason we’re here, from this perspective. It’s like flunking everyone out of first grade because we haven’t mastered algebra yet. We’re not ready. Give us time. Life’s tough enough to break every heart, several times if necessary — and to remake it bigger. OK, here endeth the lesson.

==Final Season Spoiler Alert==

Except not quite. The fourth and final season — Hulu doesn’t carry it — of “Being Erica” comes out this month on DVD, and Amazon.ca just sent email confirmation that it’s shipped. My wife and I are looking forward to watching Erica become a therapist: “Dr. Erica” in her own right. Isn’t that part of our journey, too? Out of our experience we grow, and then we can help others along the way, specifically because of who we are, and what we’ve learned. Our imperfection and individuality are our great gifts, which we grow into ever more fully. That’s an eternity to look for, if you’re in the market for one.

/|\ /|\ /|\

*Even facts prove slippery, as any attorney, judge and gathering of eyewitnesses knows. But sometimes it’s precisely a fact that makes all the difference. Then it’s usually a fact that confirms or disproves a perspective, and so it throws us back to the centrality of perspectives and understandings once again.

Image: Being Erica.

[Earth Mysteries 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7]

The second principle or law Greer examines is the Law of Flow. Before I get to it, a word about spiritual or natural laws. In my experience, we tend to think of laws, if we think of them at all, in their human variety. I break a law every time I drive over the speed limit, and most of us have broken this or some other human law more than once in our lives. We may or may not get caught and penalized by the human institutions we’ve set up to enforce the laws we’ve established, though the majority of human laws also have some common sense built in. Driving too fast, for example, can lead to its own inherent penalties, like accidents, and besides, it wastes gas.

But spiritual or natural law can’t be “broken,” any more than the law of gravity or inertia can be “broken.” Other higher laws may come into play which subsume lower ones, and essentially transform them, but that’s a different thing. A spiritual law exists as an observation of how reality tends to work, not as an arbitrary human agreement or compromise like the legal drinking age, or monogamy, or sales tax. Another way to say it: real laws or natural patterns are what make existence possible. We can’t veto the Law of Flow, or vote it down, or amend it, just because it’s inconvenient or annoying or makes anyone’s life easier or more difficult. There are, thank God, no high-powered lawyers or special-interest groups lobbying to change reality — not that they’d succeed. Properly understood, spiritual or natural law provides a guide for how to live harmoniously with life, rather than in stress, conflict or tension with it. How do I know this? The way any of us do: I’ve learned it the hard way, and seen it work the easy way — and both of these in my life and in others’ lives. Once it clicks and I “get” it, it’s more and more a no-brainer. Until then, my life seems to conspire to make everything as tough and painful as possible. Afterwards, it’s remarkable how much more smoothly things can go. Funny how that works.

But spiritual or natural law can’t be “broken,” any more than the law of gravity or inertia can be “broken.” Other higher laws may come into play which subsume lower ones, and essentially transform them, but that’s a different thing. A spiritual law exists as an observation of how reality tends to work, not as an arbitrary human agreement or compromise like the legal drinking age, or monogamy, or sales tax. Another way to say it: real laws or natural patterns are what make existence possible. We can’t veto the Law of Flow, or vote it down, or amend it, just because it’s inconvenient or annoying or makes anyone’s life easier or more difficult. There are, thank God, no high-powered lawyers or special-interest groups lobbying to change reality — not that they’d succeed. Properly understood, spiritual or natural law provides a guide for how to live harmoniously with life, rather than in stress, conflict or tension with it. How do I know this? The way any of us do: I’ve learned it the hard way, and seen it work the easy way — and both of these in my life and in others’ lives. Once it clicks and I “get” it, it’s more and more a no-brainer. Until then, my life seems to conspire to make everything as tough and painful as possible. Afterwards, it’s remarkable how much more smoothly things can go. Funny how that works.

OK, so on to the Law of Flow:

“Everything that exists is created and sustained by flows of matter, energy and information that come from the whole system to which it belongs and return to that whole system. Participating in these flows, without interfering with them, brings health and wholeness; blocking them, in an attempt to turn flows into accumulations, brings suffering and disruption to the whole system and its parts.”*

“Participating in these flows, without interfering with them,” can be a life-long quest. Lots of folks have pieces of this principle, and some of the more easily-marketed ones are available at slickly-designed websites and at New Age workshops happening near you. But note that the goal is not to accumulate wealth beyond the wildest dreams of avarice. (As Greer points out, if the so-called “Law of Attraction” really worked as advertized, the whole planet would be a single immense palace of pleasure and ease. Though who would wait on us hand and foot, wash our clothes, make our high-priced toys, or grow and cook our food, remains unclear.) Flow means drawing from system, contributing to it, and passing along its energy. “Pay it forward” wouldn’t be out of place here.

If all this sounds faintly Socialist, well, remember that as Stephen Colbert remarked, “Reality has well-known liberal bias.” It means sharing, like most of us were taught as toddlers — probably shortly after we first discovered the power and seduction of “mine!” But it could just as easily and accurately be claimed that reality has a conservative bias. After all, these are not new principles, but age-old patterns and tendencies and natural dynamics, firmly in place for eons before humans happened on the scene. To know them, and cooperate with them, is in a certain sense the ultimate conservative act. The natural world moves toward equilibrium. Anything out of balance, anything extreme, is moved back into harmony with the larger system. The flows that sustain us also shape us and link us to the system. The system is self-repairing, like the human body, and ultimately fixes itself, or attempts to, unless too much damage has occurred.

Ignorance of this law lies behind various fatuous political and economic proposals now afloat in Europe and America. Of course, what’s necessary and what’s politically possible are running further and further apart these days, and will bring their own correction and rebalancing. We just may not like it very much, until we change course and “go with the flow.” That doesn’t mean passivity, or doing it because “everybody else is doing it.” Going with the flow in the stupid sense means ignoring the current and letting ourselves be swept over the waterfall. Going with the flow in the smart sense means watching and learning from the flow, using the current to generate electricity, or mill our grain, while relying on the nature of water to buoy us up, using the flow to help carry us toward our destination. Flow is not static but dynamic, the same force that not only sustains the system, but always find the easier, quicker, optimum path: if one is not available, flow carves a new one. The Grand Canyon is flow at work over time, as are the shapes of our bodies, the curve of a bird’s wing, the curl of waves, the whorls of a seashell, the spiral arms of galaxies, the pulse of the blood in our veins. Flow is the “zone” most of us have experienced at some point, that energy state where we are balanced and in tune, able to create more easily and smoothly than at other times. Hours pass, and they seem like minutes. Praised be flow forever!

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: river.

*Greer, John Michael. Mystery Teachings from the Living Earth. Weiser, 2012.

Druid teaching, both historically and in contemporary versions, has often been expressed in triads — groups of three objects, perceptions or principles that share a link or common quality that brings them together. An example (with “check” meaning “stop” or “restrain”): “There are three things not easy to check: a cataract in full spate, an arrow from a bow, and a rash tongue.” Some of the best preserved are in Welsh, and have been collected in the Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Triads of the Island of Britain*, pronounced roughly tree-oyth un-iss pruh-dine). The form makes them easier to remember, and memorization and mastery of triads were very likely part of Druidic training. Composing new ones offers a kind of pleasure similar to writing haiku — capturing an insight in condensed form. (One of my favorite haiku, since I’m on the subject:

Druid teaching, both historically and in contemporary versions, has often been expressed in triads — groups of three objects, perceptions or principles that share a link or common quality that brings them together. An example (with “check” meaning “stop” or “restrain”): “There are three things not easy to check: a cataract in full spate, an arrow from a bow, and a rash tongue.” Some of the best preserved are in Welsh, and have been collected in the Trioedd Ynys Prydein (The Triads of the Island of Britain*, pronounced roughly tree-oyth un-iss pruh-dine). The form makes them easier to remember, and memorization and mastery of triads were very likely part of Druidic training. Composing new ones offers a kind of pleasure similar to writing haiku — capturing an insight in condensed form. (One of my favorite haiku, since I’m on the subject:

Don’t worry, spiders —

I keep house

casually.

— Kobayashi Issa**, 1763-1827/translated by Robert Hass)

A great and often unrecognized triad appears in the Bible in Matthew 7:7 (an appropriately mystical-sounding number!). The 2008 edition of the New International Version renders it like this: “Keep asking, and it will be given to you. Keep searching, and you will find. Keep knocking, and the door will be opened for you.”

Apart from the obvious exhortation to persevere, there is much of value here. Are all three actions parallel or equivalent? To my mind they differ in important ways. Asking is a verbal and intellectual act. It involves thought and language. Searching, or seeking, may often be emotional — a longing for something missing, a lack or gap sensed in the soul. Knocking is concrete, physical: a hand strikes a door. All three may be necessary to locate and uncover what we desire. None of the three is raised above the other two in importance. All of them matter; all of them may be required.

And what are we to make of this exhortation to keep trying? Many cite scripture as if belief itself were sufficient, when verses like this one make it clear that’s not always true. Spiritual achievement, like every other kind, demands effort. Little is handed to us without diligence on our part.

And what are we to make of this exhortation to keep trying? Many cite scripture as if belief itself were sufficient, when verses like this one make it clear that’s not always true. Spiritual achievement, like every other kind, demands effort. Little is handed to us without diligence on our part.

And though the three modes of investigation or inquiry aren’t apparently ranked, it’s long seemed to me that asking is lowest. If you’ve got nothing else, try a simple petition. It calls to mind a child asking for a treat or permission, or a beggar on a street-corner. The other two modes require more of us — actual labor, either of a quest, or of knocking on a door (and who knows how long it took to find?).

It’s possible to see the three as a progression, too — a guide to action. First, ask in order to find out where to start, at least, if you lack other guidance. With that hint, begin the quest, seeking and searching until you start “getting warm.” Once you actually locate what you’re looking for — the finding after the seeking — it’s time to knock, to try out the quest physically, get the body involved in manifesting the result of the search. Without this vital third component of the quest, the “find” may never actually make it into life where we live it every day.

Sometimes the knocking is initiated “from the other side” In Revelations, the Galilean master says, “I stand at the door and knock.” Here the key seems to be to pay attention and to open when you hear a response to all your seeking and searching. The universe isn’t deaf, though it answers in its own time, not ours. The Wise have said that the door of soul opens inward. No point in shoving up against it, or pushing and then waiting for it to give, if it doesn’t swing that way …

/|\ /|\ /|\

*The standard edition of the Welsh triads for several decades is the one shown in the illustration by Rachel Bromwitch, now in its 3rd edition. The earliest Welsh triads appearing in writing date from the 13th century.

**Issa (a pen name which means “cup of tea”) composed more than 20,000 haiku. You can read many of them conveniently gathered here.

book cover; door image.

Ah, Fifth Month, you’ve arrived. In addition to providing striking images like this one, the May holiday of Beltane on or around May 1st is one of the four great fire festivals of the Celtic world and of revival Paganism. Along with Imbolc, Lunasa and Samhain, Beltane endures in many guises. The Beltane Fire Society of Edinburgh, Scotland has made its annual celebration a significant cultural event, with hundreds of participants and upwards of 10,000 spectators. Many communities celebrate May Day and its traditions like the Maypole and dancing (Morris Dancing in the U.K.). More generally, cultures worldwide have put the burgeoning of life in May — November if you live Down Under — into ritual form.

Ah, Fifth Month, you’ve arrived. In addition to providing striking images like this one, the May holiday of Beltane on or around May 1st is one of the four great fire festivals of the Celtic world and of revival Paganism. Along with Imbolc, Lunasa and Samhain, Beltane endures in many guises. The Beltane Fire Society of Edinburgh, Scotland has made its annual celebration a significant cultural event, with hundreds of participants and upwards of 10,000 spectators. Many communities celebrate May Day and its traditions like the Maypole and dancing (Morris Dancing in the U.K.). More generally, cultures worldwide have put the burgeoning of life in May — November if you live Down Under — into ritual form.

I’m partial to the month for several reasons, not least because my mother, brother and I were all born in May. It stands far enough away from other months with major holidays observed in North America to keep its own identity. No Thanksgiving-Christmas slalom to blunt the onset of winter with cheer and feasting and family gatherings. May greens and blossoms and flourishes happily on its own. It embraces college graduations and weddings (though it can’t compete with June for the latter). It’s finally safe here in VT to plant a garden in another week or two, with the last frosts retreating until September. At the school where I teach, students manage to keep Beltaine events alive even if they pass on other Revival or Pagan holidays.

I’m partial to the month for several reasons, not least because my mother, brother and I were all born in May. It stands far enough away from other months with major holidays observed in North America to keep its own identity. No Thanksgiving-Christmas slalom to blunt the onset of winter with cheer and feasting and family gatherings. May greens and blossoms and flourishes happily on its own. It embraces college graduations and weddings (though it can’t compete with June for the latter). It’s finally safe here in VT to plant a garden in another week or two, with the last frosts retreating until September. At the school where I teach, students manage to keep Beltaine events alive even if they pass on other Revival or Pagan holidays.

The day’s associations with fertility appear in Arthurian lore with stories of Queen Guinevere’s riding out on May Day, or going a-Maying. In Collier’s painting above, the landscape hasn’t yet burst into full green, but the figures nearest Guinevere wear green, particularly the monk-like one at her bridle, who leads her horse. Guinevere’s affair with Lancelot eroticized everything around her — greened it in every sense of the word. Tennyson in his Idylls of the King says:

The day’s associations with fertility appear in Arthurian lore with stories of Queen Guinevere’s riding out on May Day, or going a-Maying. In Collier’s painting above, the landscape hasn’t yet burst into full green, but the figures nearest Guinevere wear green, particularly the monk-like one at her bridle, who leads her horse. Guinevere’s affair with Lancelot eroticized everything around her — greened it in every sense of the word. Tennyson in his Idylls of the King says:

For thus it chanced one morn when all the court,

Green-suited, but with plumes that mocked the may,

Had been, their wont, a-maying and returned,

That Modred still in green, all ear and eye,

Climbed to the high top of the garden-wall

To spy some secret scandal if he might …

Of course, there are other far more subtle and insightful readings of the story, ones which have mythic power in illuminating perennial human challenges of relationship and energy. But what is it about green that runs so deep in European culture as an ambivalent color in its representation of force?

Of course, there are other far more subtle and insightful readings of the story, ones which have mythic power in illuminating perennial human challenges of relationship and energy. But what is it about green that runs so deep in European culture as an ambivalent color in its representation of force?

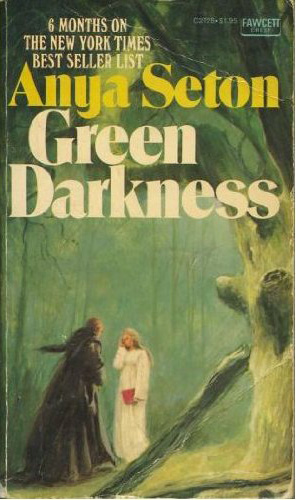

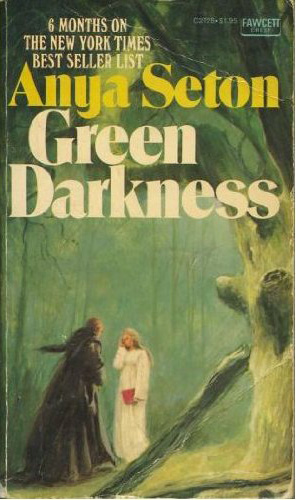

Anya Seton’s novel Green Darkness captures in its blend of Gothic secrecy, sexual obsession, reincarnation and the struggle toward psychic rebalancing the full spectrum of mixed-ness of green in both title and story. As well as the positive color of growth and life, it shows its alternate face in the greenness of envy, the eco-threat of “greenhouse effect,” the supernatural (and original) “green giant” in the famous medieval tale Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the novel and subsequent 1973 film Soylent Green, and the ghostly, sometimes greenish, light of decay hovering over swamps and graveyards that has occasioned numerous world-wide ghost stories, legends and folk-explanations.

(Wikipedia blandly scientificizes the phenomenon thus: “The oxidation of phosphine and methane, produced by organic decay, can cause photon emissions. Since phosphine spontaneously ignites on contact with the oxygen in air, only small quantities of it would be needed to ignite the much more abundant methane to create ephemeral fires.”) And most recently, “bad” greenness showed up during this year’s Earth Day last month, which apparently provoked fears in some quarters of the day as evil and Pagan, and a determination to fight the “Green Dragon” of the environmental movement as un-Christian and insidious and horrible and generally wicked. Never mind that stewardship of the earth, the impetus behind Earth Day, is a specifically Biblical imperative (the Sierra Club publishes a good resource illustrating this). Ah, May. Ah, silliness and wisdom and human-ness.

We could let a Celt and a poet have (almost) the last word. Dylan Thomas catches the ambivalence in his poem whose title is also the first line:

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

The force that drives the water through the rocks

Drives my red blood; that dries the mouthing streams

Turns mine to wax.

And I am dumb to mouth unto my veins

How at the mountain spring the same mouth sucks.

The hand that whirls the water in the pool

Stirs the quicksand; that ropes the blowing wind

Hauls my shroud sail …

Yes, May is death and life both, as all seasons are. But something in the irrepressible-ness of May makes it particularly a “hinge month” in our year. The “green fuse” in us burns because it must in order for us to live at all, but our burning is our dying. OK, Dylan, we get it. Circle of life and all that. What the fearful seem to react to in May and Earth Day and things Pagan-seeming is the recognition that not everything is sweetness and light. The natural world, in spite of efforts of Disney and Company to the contrary, devours as well as births. Nature isn’t so much “red in tooth and claw” as it is green.

Yes, things bleed when we feed (or if you’re vegetarian, they’ll spill chlorophyll. Did you know peas apparently talk to each other?). And this lovely, appalling planet we live on is part of the deal. It’s what we do in the interim between the “green fuse” and the “dead end” that makes all the difference, the only difference there is to make. So here’s Seamus Heaney, another Celt and poet, who gives us one thing we can do about it: struggle to make sense, regardless of whether or not any exists to start with. In his poem “Digging,” he talks about writing, but it’s “about” our human striving in general that, for him, takes this particular form. It’s a poem of memory and meaning-making. We’re all digging as we go.

Digging

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; as snug as a gun.

Under my window a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade,

Just like his old man.

My grandfather could cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, digging down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mold, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Beltane Fire Society image; Maibaum; John Maler Collier’s Queen Guinevere’s Maying; Soylent Green; Green Darkness; peat.

“Only what is virgin can be fertile.” OK, Gods, now that you’ve dropped this lovely little impossibility in my lap this morning, what am I supposed to do with it? Yeah, I get that I write about these things, but where do I begin? “Each time coming to the screen, the keyboard, can be an opportunity” — I know that, too. But it doesn’t make it easier. Why don’t you try it for a change? Stop being all god-dy and stuff and try it from down here. Then you’ll see what it’s like.

OK, done? Fit of pique over now?

I never had much use for prayer. Too often it seems to consist either of telling God or the Gods what to do and how to do it (if you’re arrogant) or begging them for scraps (if they’ve got you afraid of them, on your knees for the worst reasons). But prayer as struggle, as communication, as connecting any way you can with what matters most — that I comprehend. Make of this desire to link an intention. A daily one, then hourly. Let if fill, if if needs to, with everything in the way of desire, and hand that back to the universe. Don’t worry about Who is listening. Your job is to tune in to the conversation each time, to pick it up again. And the funny thing is that once you stop worrying about who is listening, everything seems to be listening (and talking). Then the listening rubs off on you as well. And you finally shut up.

That’s the second half, often, of the prayer. To listen. Once the cycle starts, once the pump gets primed, it’s easier. You just have to invite and welcome who you want to talk with. Forget that little detail, and there can be lots of other conversations on the line. The fears and dreams of the whole culture. Advertisers get in your head, through repetition. (That’s why it’s best to limit TV viewing, or dispense with it altogether, if you can. Talk about prayer out of control. They start praying you.) They’ve got their product jingle and it’s not going away. Sometimes all you’ve got in turn is a divine product jingle. It may be a song, a poem, a cry of the heart. The three Orthodox Christian hermits of the great Russian novelist Tolstoy have their simple prayer to God: “We are three. You are three. Have mercy on us!” Over time, it fills them, empowers them. They become nothing other than the prayer. They’ve arrived at communion.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Equi-nox. Equal night and day. The year hanging, if only briefly, in the balance of energies. Spring, a coil of energy, poised. The earth dark and heavy, waiting, listening. The change in everything, the swell of the heart, the light growing. Thaw. The last of the ice on our pond finally yields to the steady warmth of the past weeks, to the 70-degree heat of Tuesday. The next day, Wednesday, my wife sees salamanders bobbing at the surface. Walk closer, and they scatter and dive, rippling the water.

/|\ /|\ /|\

I once heard a Protestant clergywoman say to an ecumenical assembly, “We all know there was no Virgin Birth. Mary was just an unwed, pregnant teenager, and God told her it was okay. That’ s the message we need to give girls today, that God loves them, and forget all this nonsense about a Virgin birth.” … I sat in a room full of Christians and thought, My God, they’re still at it, still trying to leach every bit of mystery out of this religion, still substituting the most trite language imaginable …

The job of any preacher, it seems to me, is not to dismiss the Annunciation because it doesn’t appeal to modern prejudices, but to remind congregations of why it might still be an important story (72-73).

So Kathleen Norris writes in her book Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith. She goes on to quote the Trappist monk, poet and writer Thomas Merton, who

describes the identity he seeks in contemplative prayer as a point vierge [a virgin point] at the center of his being, “a point untouched by illusion, a point of pure truth … which belongs entirely to God, which is inaccessible to the fantasies of our own mind or the brutalities of our own will. This little point … of absolute poverty,” he wrote, “is the pure glory of God in us” (74-5).

So if I need to, I pull away the God-language of another tradition and listen carefully “why it might still be an important story.” Not “Is it true or not?” or “How can anybody believe that?” But instead, why or how it still has something to tell me. Another kind of listening, this time to stories, to myths, our greatest stories, for what they still hold for us.

One of the purest pieces of wisdom I’ve heard concerns truth and lies. There are no lies, in one sense, because we all are telling the truth of our lives every minute. It may be a different truth than we asked for, or than others are expecting, but it’s pouring out of us nonetheless. Ask someone for the truth, and if they “lie,” their truth is that they’re afraid. That knowledge, that insight, may well be more important than the “truth” you thought you were looking for. “Perfect love casteth out fear,” says the Galilean. So it’s an opportunity for me to practice love, and take down a little bit of the pervasive fear that seems to spill out of lives today.

Norris arrives at her key insight in the chapter:

But it is in adolescence that the fully formed adult self begins to emerge, and if a person has been fortunate, allowed to develop at his or her own pace, this self is a liberating force, and it is virgin. That is, it is one-in-itself, better able to cope with peer pressure, as it can more readily measure what is true to one’s self, and what would violate it. Even adolescent self-absorption recedes as one’s capacity for the mystery of hospitality grows: it is only as one is at home in oneself that one may be truly hospitable to others–welcoming, but not overbearing, affably pliant but not subject to crass manipulation. This difficult balance is maintained only as one remains [or returns to being] virgin, cognizant of oneself as valuable, unique, and undiminishable at core (75).

/|\ /|\ /|\

This isn’t where I planned to go. Not sure whether it’s better. But the test for me is the sense of discovery, of arrival at something I didn’t know, didn’t understand in quite this way, until I finished writing. Writing as prayer. But to say this is a “prayer blog” doesn’t convey what I try to do here, or at least not to me, and I suspect not to many readers. A Druid prayer comes closer, it doesn’t carry as much of the baggage as the word “prayer” may carry for some readers, and for me. “I’m praying for you,” friends said when I went into surgery three years ago. And I bit my tongue to keep from replying, “Just shut up and listen. That will help both us a lot more.” So another way of understanding my blog: this is me, trying to shut up and listen. I talk too much in the process, but maybe the most important part of each post is the silence after it’s finished, the empty space after the words end.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Norris, Kathleen. Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith. New York: Riverhead Books, 1998.

An altar is an important element of very many spiritualities around the world. It gives a structure to space, and orients the practitioner, the worshipper, the participant (and any observers) to objects, symbols and energies. It’s a spiritual signpost, a landmark for identifying and entering sacred space. It accomplishes this without words, simply by existing. The red color of the Taoist altar below immediately alerts the eye to its importance and energy.

As a center of ritual action and visual attention, an altar is positioned to draw the eye as much as any other sense. In Christian churches like the one below, everything is subordinated to the Cross and the altar immediately below it. Church architecture typically highlights this focus through symmetry and lighting. But in every case, enter the sacred space which an altar delineates, and it tells you what matters by how it is shaped and ordered and organized.

Part of OBOD* training is the establishment and maintenance of a personal altar as part of regular spiritual practice. Here’s a Druid altar spread on a tabletop. Nothing “mundane” or arbitrary occupies the space — everything has ritual or spiritual purpose and significance to its creator.

Such obviously physical objects and actions and their appeal to the senses as aids in spiritual practice all spring from human necessity. We need the grounding of our practices in the physical world of words, acts and sensations in order to “bring them home to us,” and make them real or “thingly,” which is what “real” (from Latin res “thing”) means.

Religions and spiritual teachings accomplish this in rich and diverse ways. We have only to think of Christian baptism, communion and the imposition of ashes at Easter; Hindu prasad and tilak; Jewish bris/brit (circumcision) and tallit (prayer shawl) and so on.

Atheists who focus exclusively on belief in their critiques and debates thus forget the very real, concrete and physical aspects of religious and spiritual practice which invest actions, objects and words with spiritual meaning that cannot be dismissed merely by pointing out any logical or rational cracks in a set of beliefs. Though you may present “evidence that God doesn’t exist” that seems irrefutable to you, you haven’t even begun to touch the beauty of an altar or spiritual structure, the warmth of a religious community of people you know and worship with, the power of a liturgy, the smell of incense, the tastes of ritual meals, the sounds of ritual music and song.

Just as we hear people describe themselves as “spiritual without being religious” as they struggle to sift forms of religion from the supposed “heart” of spirituality, plenty of so-called “believers” are “religious without being spiritual.” The forms of their spiritual and religious practice are rich with association, memory and community, and can be as important as — or more so than — a particular creed or set of beliefs.

Having said all of this, I’ve had a set of experiences that incline me away from erecting a physical altar for my Druid practice. So I’m working toward a solution to the spiritual “problem” this presents. Let me approach it indirectly. Once again, and hardly surprising to anyone who’s followed this blog or is as bookish as I am, the trail runs through books.

Damiano, the first volume in a fabulous (and sadly under-known) trilogy by R. A. MacAvoy, and recently reissued as part of an omnibus edition called Trio for Lute, supplies an image for today’s post. Damiano Delstrego is a young Renaissance Italian who happens to be both witch and aspiring musician. His magic depends for its focus on a staff, and we see both the strengths and limitations of such magical tools in various episodes in the novel, and most particularly when he encounters a Finnish woman who practices a singing magic.

When I read the trilogy at its first publication in the 80s, the Finnish magic sans tools seemed to me much superior to “staff-based” power. (Partly in the wake of Harry Potter and the prevalence of wands and wand-wielders in the books and films, there’s a resurgence of interest in this aspect of the art, and an interesting new book just published reflecting that “tool-based” bias, titled Wandlore: the Art of Crafting the Ultimate Magical Tool).

So when I then read news of church burnings, desecrated holy sites, quests for lost spiritual objects (like the Holy Grail) and so on, the wisdom of reposing such power in a physical object seemed to me dubious at best. For whatever your own beliefs, magic energy — whether imbued by intention, Spirit, habit, the Devil, long practice, belief in a bogus or real power — keeps proving perilously vulnerable to misplacement, loss or wholesale destruction. Add to this Jesus’ observation that we are each the temple of Spirit, and my growing sense of the potential of that inner temple of contemplation — also a feature of OBOD practice — and you get my perspective.

Carrying this admitted bias with me over the years, when I came last year to the lesson in the OBOD Bardic series that introduced the personal altar, I realized I would need both contemplation and creativity to find my way.

My solution so far is a work in progress, an alpha or possibly a beta version. My altar is portable, consisting of just five small stones, one for each of the classic European five elements — four plus Spirit. Of course I have other associations, visualizations and a more elaborate (and still evolving) practice I do not share here. But you get the idea. (If you engage in a more Native-American nourished practice, you might choose seven instead: the four horizontal directions, above [the zenith], below [the nadir] and the center.)

I can pocket my altar in a flash, and re-deploy it on a minimal flat space (or — in a pinch — right on the palm of my hand). One indulgence I’ve permitted myself: the stones originate from a ritual gift, so they do in fact have personal symbolic — or magical, if you will — significance for me. But each altar ritual I do includes both an invitation for descent and re-ascent of power or imagery or magic to and away from the particular stones that represent my altar. Lose them, and others can take their place for me with minimal ritual “loss” or disruption. Time and practice will reveal whether this is a serviceable solution.

This post is already long enough, so I’ll defer till later any discussion of the fitness of elemental earth/stone standing in for the other elements.

/|\ /|\ /|\

*OBOD — the particular “flavor” of Druidry I’m studying and practicing.

Images: Singapore Taoist altar; Christian altar; Druid altar; Amazon/Trio for Lute.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Updated: 27 July 2013

The start of the year is a good time to look back and forward too, in as many ways as it fits to do so. If you’ve got a moment, think about what stands out for you among your hopes for this new year, and you strongest memories of the year past. What’s the link between them? Is there one? Here we are in the middle, between wish and memory. In his great and intellectually self-indulgent poem “The Waste Land,” Eliot said “April is the cruelest month, mixing memory and desire.” But April need not be cruel — we can make any month crueler, or kinder — and neither should January. Let’s take a sip of the mental smoothie of memory and desire that often passes for consciousness during most of our waking hours, and consider.

To recap from previous posts, if we’re looking for a workable and bug-free Religious Operating System, we can start with persistence, initiation and magic (working in intentional harmony with natural patterns). You’ll note that all of these are things we do — not things a deity, master or Other provides for us. While these latter sources of life energy, insight and spiritual momentum can matter a great deal to our growth and understanding, nothing replaces our own efforts. Contrary to popular understanding, no one else can provide salvation without effort on our part. We can “benefit” from a spiritual welfare program only if we use the shelter of the divine to build something of our own. Yes, a mother eats so she can feed the fetus growing within her, but only in preparation for it to become an independent being that can eat on its own. We may take refuge with another, but for the purpose of gaining or recovering our own spiritual stamina. If we’re merely looking for a handout and unwilling to do anything ourselves, we end up “running in our own debt,” Emerson termed it. We weaken, rather than grow stronger.