Author Archive

[Posts on previous Gatherings: ECG ’12 ][ ’13 ][ ’14 ][ ’15 ][ ’16 ][ ’17 ][ MAGUS ’17 ][ MAGUS ’18 ]

How to convey the distinctive experience of a Gathering? Perhaps you come for a group initiation, having already performed the solo rite.

initiates and officiators, after the Bardic initiations

ECG initiated 10 Bards, 4 Ovates, and 1 Druid in three rituals over the four-day weekend.

Nearly-full moon on the night of Ovate initiations — photo courtesy Gabby Roberts

Or maybe the title of a particular workshop or the reputation of a presenter draws you. Though registration records for ECG show that each year about 40% of the attendees are first-timers, guest speakers and musicians play a role in swelling the numbers of multi-year attendees.

Kris Hughes

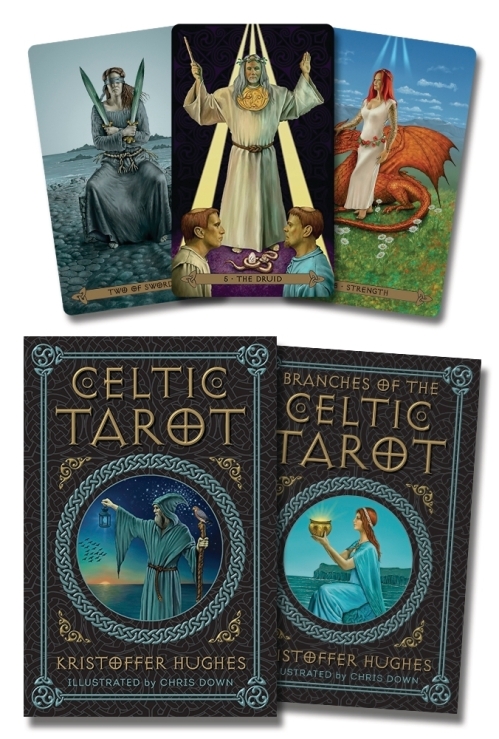

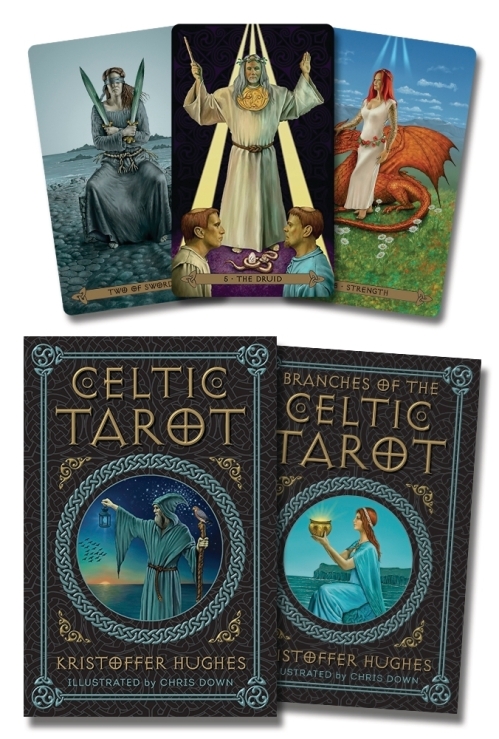

Returning special guest Kristoffer Hughes gave two transformative talks: “Taw, Annwfn and the Hidden Heart of Awen”, and “Tarot Masterclass”.

The first talk effectively conveyed how awen is much more than we typically conceive it. As the “Heart-song of the World”, it pervades existence, from Annwfn, often translated as the Celtic “Otherworld” but more accurately rendered the “Deep World” (which the Welsh word literally means), through Abred — this world we live in and conventionally treat as reality, and which Annwfn underpins, all the way through Gwynfyth and Ceugant. As for “the hidden magic that swims within the currents of Awen”, excerpted from the description of the talk on the ECG website, awen is available to us and links us to other beings resting and moving in the Song. And “one practice that can open these connections is to sing to things. Sometimes trees talk, and sometimes they listen. Especially when we sing to them. And we may find they sing back”, Kris remarked.

With his characteristic wit and insight, Kris illustrated parallels between the secular Welsh eisteddfod bardic competitions and the work and practice of Druidry. We want to practice ways to increase the flow of awen, whether we’re poets in a competition or living our everyday lives. “You’re Druids. You’re busy. You’ve got sh*t to do and trees to talk to”.

At the height of the bardic competition, if no poems that year meet the eisteddfod standard, the eisteddfod assembly hears the terrible cry of the Archdruid — “There is no awen here. Shame!” But in most years, when a winner does succeed and is crowned, the Archdruid “whispers a secret into the Bard’s ear, changing him or her forever. Learn what that secret is”. The “appeal of the secret” flourishes long after childhood; Kris remarked that the secret is a three-vowel chant a-i-o, one form of the “sound of the awen”, without consonants, which cut off the flow of sound. So we practiced vowels, with Kris remarking that even the word awen itself, minus the final -n, can serve very well as one form of the chant.

What of the taw of the talk title? It’s the Welsh word for silence, or more especially, tranquillity, translatable, Kris writes in a related blogpost, “as a deep inner silence, stillness and peacefulness … not simply the external expression or desire for Hedd (peace) alone, but rather how Hedd transforms the internal constitution of the individual. And to achieve this we utilise Taw“.

I took extensive notes for the Tarot talk, for which Kris relied to some degree on his Celtic Tarot book, but for this talk on awen and taw, I listened. Kris writes, “Taw is when I sit in the woods, or on the edge of my local beach, with starlight painting dreams in the night sky. Within it I sit in the delicious currents of Awen and allow it to flow through me. What sense I make of that comes later. How can I hope to bring Hedd into the world if I cannot find the Hedd within myself? If I cannot inspire myself, how on earth can I inspire anyone else? I need Taw to cause me to remember who I am and what I am”.

And he closed this talk, saying, “I’ve been Kristoffer Hughes, and you’ve been … the awen”.

Image at Llywellyn Press site for Celtic Tarot:

I include this because I asked Kris about his experiences with publishers and about where best to order the book (I like to meditate and ask if I need a particular book rather than buying it on the spot.) Kris said, “Through Llywellyn I earn about $1.40 for each book. Through Amazon, because of their deal with Llywellyn, I earn about 12 cents”. So if you’re inclined to purchase this stunning set and learn Kris’s no-nonsense and eminently usable techniques — “you don’t have to be psychic; you need to be able to tell stories, which is something Druids do” — bear those numbers in mind.

/|\ /|\ /|\

This year for the first time, rather the ECG staff manning the kitchen, the Netimus Camp staff took over meals, freeing up camp volunteers and doing an excellent job of feeding and nourishing us.

Chris Johnstone’s Sound Healing workshop greeted us Thursday, the first day, an excellent antidote to the stresses of travel to reach the camp, and a reminder, always needed, that we never abandon foundational practices of centering and meditation, ritualizing and balance.

“pasta awen” — Druid humor. Photo courtesy Russell Rench.

Gabby Roberts’ workshop, “Energy work–Grounding, Centering and Releasing”, deepened the reminder, and gifted us each with polished onyxes to take with us. “Awareness and Connection with the Land: A Druidic Perspective”, with Thea Ruoho and Erin Rose Conner, detailed the many unconscious moments we can transform in order to be more conscious and mindful living on the earth. Thea and Erin ended their talk with an invitation for us to recycle, burn in the fire circle, or give back the “sacred crap” we can accumulate, that litters our shelves and altars, but contributes no energy.

Gathering attendee prepping for Druid Staff workshop

I missed Christian Brunner’s provocatively titled “A Journey to the Very Old Gods” due to an important conversation I needed to continue; the same thing happened a second time with Frank Martinez’s “Connecting with the Plant Community Through a Druid’s Staff”. Thus go the rhythms of a Gathering, which for me, anyway, almost seem to require a rhythm that may take you away from one or two sessions to something or someone else, calling you with imperatives all their own.

Most days of the year, of course, we’re all solitaries, whether we practice alone by choice or necessity, or enjoy the intermittent company of a few others in a local Pagan community, an OBOD Seed Group, or a full Grove. Each day we greet the light and air and season, attend to bird and beast and bee and tree, and our own bodies and lives, and listen for that heartsong. So a Gathering, camp, retreat, etc., is no panacea, but it does give us a chance to reconnect, recharge, recalibrate what we do and where we’re heading. Its ripples persist after the “hour of recall” comes at the close of a Gathering.

On Saturday, the last evening, the ECG organizer announced at dinner that this 9th year of the Gathering has seen the fulfillment of its initial goals and will be the last year. ECG has served newcomers well, linked practitioners over the years, offered a family-friendly space (which not all camps choose to do), helped us forge friendships, seeded new camps and Gatherings — including Gulf Coast Gathering and Mid-Atlantic Gathering U.S. (MAGUS), and provided a supportive venue for group initiations for those wishing that experience.

A Council is already in place to help organize a new event that will launch next year, with new energy, goals, and intentions. As the organizer exclaimed, “Watch for it!”

OBOD standard ritual closes with these words: “As the fire dies down, may it be relit in our hearts. May our memories hold what the eye and ear have gained”.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Images: Kris Hughes; Llywellyn Press Celtic Tarot.

“Human cognitive powers have a seasonal rhythm, and for those living in temperate regions in the northern hemisphere they are strongest in late summer and early autumn”, says an article in the 4 Sept 2018 New Scientist (subscription req’d for full article).

We can assume, in spite of the article’s “hemispherism” (a tendency to privilege the northern hemisphere, or exclude the southern one from consideration altogether), that a similar rhythm holds true for the southern hemisphere in their late summer and early autumn, while the north slumbers uneasily beneath snow and cold in late winter and early spring. Southern friends, if you’re so inclined, bookmark this and return to read it when it’s more seasonally appropriate for your Land.

It stands to reason that harvest, with its demands for food preparation, its expanded food sources and increased nutrition, its social gatherings and preparations for the coming winter, would draw on and amplify human capacities of every kind, cognitive powers included. The lethargy of the heat of high summer has passed, and that crisp tang in the air and the red and golds that blanket hillsides in New England in particular, and draw so many to name autumn our favorite season, all conspire to spur us to activity. In the U.S., schools re-open, and you can feel the tilt and shift of the change from summer from late August through September.

Pagan and Magical Orders have long identified the equinoxes as times of particular inner activity. Initiations in many Orders take advantage of this heightening for its boost to ritual. By pairing our actions with what happens to the planet, we harmonize with currents deeper and more lasting than “what’s new” or what reaches the headlines or media-feeds on our preferred sources of gafs — gossip, advertising, fear-mongering, and sensationalism — that we still call “news”.

For what is truly “new” has of course been going on just beyond our noses all the while. The earth shifts and rebalances every moment. Plants renew the air, and we can keep breathing; they send forth seed and fruit, and we can keep eating. In spite of human assumptions, they’re under no obligation to do so, yet they gift us with their own substance year after year, just as we feed them with our breathing and our waste and our own bodies when they wear out. Break the cycle we’ve built together over eons, each learning the others’ gestures and energies and characters, and the relationship falters, like any relationship we no longer tend.

The initiation of cause and effect, which the Wise tell us we have repeatedly rejected corporately as a planet, has not disappeared or been switched off, or cast aside for something better. It still awaits our preparation and acceptance. With it, we can heal and create and thrive and change. That doesn’t mean it leads to heaven, or the apocalypse, or the Singularity. It’s simply life. And without it, we do what we always do when we reject growth. We stagnate, suffer strange outbreaks of dis-ease, regress, accumulate toxins, bloat, stifle, blame, blunder, and flail about. We cannot stand still, so if we don’t progress, we lurch backward, trampling new growth. The cosmos mirrors itself back in our awareness. We get what we give.

dew on spiderwebs earlier this a.m.

The first glimmers of acceptance of the initiation spring up around us in individuals who have taken another step. And each of us has, in small and larger ways. Chickens come home to roost politically and environmentally. Mass consciousness shifts by fits and starts, even as individual consciousnesses grapple with change, whether each welcomes or fears it, resists it or works with it. The tipping point, however, is not yet. What we cannot force for the planet, however, we can navigate and midwife for ourselves and our closer circles. This will help more than almost anything else, because it prepares us to weather and grow through further changes and trials, even to flourish, and find joy.

Autumn renews in a different fashion than Spring. We are not seeding, at least not right away. Instead, we gather seed. We take stock, store up, brew, reap, glean. We’re weatherizing, stock-piling, fermenting, pickling, consolidating. We are, in the fuller old sense of the word, brooding, as a hen does its eggs. The soft yet edged light of September bathes days when the sun shows, a goldenrod month, a month of falcons.

Septem is “seven” in the older Roman calendar, the seventh month, counting from the similarly old beginning of the year in March. Seven is fullness, the sum of the 4 of the earth’s quarters and the 3 of the eternal cycle. Now that it’s also the ninth month in most current calendars, it draws as well on the magical symbolism of that number, a three of threes.

Rather than troubling overmuch about whether such associations are “true”, it can be more fruitful to see how and when they might be useful or accurate or faithful metaphors or maps or representations, and for which of the many different states of consciousness we all pass through.

Autumn, like every season, offers itself as a contour map of brains that have evolved over millions of autumns. What we see mirrors the tool with which we see it.

The blessings of autumn on us all.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Finding out about how we ourselves “do Druidry” — or other path we’re on — is a key step that all of us, it seems, keep taking. From that personal connection and insight, renewed over time and through our own experiences, comes a growing confidence in our own strengths and uniqueness that others can’t easily shake. It’s no longer just faith, but communion. It’s bone-knowledge, gut-wisdom, skin-sense. We know things, in that lovely old expression, by heart.

The more our practice, whatever it is, rests as much in doing as in believing, the more we draw strength from it in ways that can feel surprisingly like physical exercise. Our bodies learn to know our practice as well as our brains. Oak or rowan or beech become friends — our community has grown through knowing individuals, no longer just abstractions in a listing of trees in an ogham-book. The welcome of oak differs from the subtler touch that rowan extends. And these two differ from maple or hemlock. And so on through all the other furry, winged and finned kindred we encounter in the land where we find ourselves.

The work of any Order worth my energy and dedication will contain material that speaks clearly to me and seems just right. There will also be exercises and insights that I can adapt, and still others that are right to set aside for a time until they align with what I’m doing and needing to do. One of the signal advantages of an Order is its span: many hands and hearts have sifted material I might never encounter on my own, and wiser heads than mine have added insights, caveats and encouragements that I might otherwise miss. The work of an Order is more compact, in valuable ways, than the work of a Solitary. It’s denser, richer in certain ways, brewed and spiced, aged and tempered, refined and mellowed, sharpened and lit.

It also vibrates on a harmonic that reaches others attuned to it. Doing the rituals, passing through the initiations, studying and reflecting on and trying out the coursework, meeting others doing the same things, all bring me into a greater circle I discover I need, no matter how solitary I am — and need to be — most of the time. The choice, as it so often does, arises from the richness of both-and, not either-or. I find that I come not to a fork in the path, but the path itself opening out, for a time, into a meadow. Beyond is vista: mountains, maybe, or valleys shining with silver rivers, towns bright with banners and laughter. Quests beckon, mysteries abound. It’s no surprise that a medieval landscape features in so many modern dreams and deeds, with both real danger and jewelled possibility a heartbeat or horse-ride away. Just over the next hill, or back at the castle, down a corridor we never knew was there.

In the West we pursue ever more isolated and internal lives, busy too often with busy-ness itself, all the while crying out for the gifts of community we simultaneously keep turning away from: connection, fellowship, camaraderie, friendship, shared interests and inspirations, shared suffering and joy. Well-founded community sees that spark of individuality restored to a healthy place, one that does not render me less able to connect, but more; one that honors my need to withdraw at times, even as I also need to open to others; one that sweeps me out of indifference toward engagement with the struggles of others anywhere, who turn out to be surprisingly like me after all. We be of one blood, ye and I.

first fire, a few days ago

Along with Groucho Marx, many of us may have grumbled some version of I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept people like me as members. And knowing ourselves as we do, maybe we’re right to say that. On our off days, we’re off on ourselves as much as anyone else. Hamlet’s our doppelganger, midwife to angst and depression and self-accusation: I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more offences at my beck than I have thoughts to put them in, imagination to give them shape, or time to act them in. What should such fellows as I do, crawling between earth and heaven?

Somehow “joining an Order” just doesn’t seem like any kind of sane response to that question, but more like the absolute last thing I would choose. Isn’t there a twilit bar or pub nearby where I can hide and drown my sorrows?

And certainly Orders aren’t any kind of cure-all or panacea. As human institutions, they’re potentially beset with all the human foibles we know so well in ourselves. Personalities clash, dreams backfire and scorch, visions implode, egos lunge and stab. We peer around at the wreckage, bandage the worst of our wounds, and vow: never again.

But Orders can also launch us toward the heights that we know or dream of, or — if we’re particularly cynical right now — doubt are possible at all: they focus and help to nourish the deepest hungers in us, beyond food or sex. In the connections they aid us in making, we touch on something that lifts us out of ourselves, we’re part of that never-ending story our best dreamers keep singing about to us, and painting, and weaving, and nudging us to explore.

/|\ /|\ /|\

A precipitous drop in temperatures from the 90s (34C) to the 40s (6C) last night, warming to the low 60s (17C) this afternoon, made for ideal conditions to visit the stone chambers around Putney, Vermont.

My Druid friend B. was my guide. The roads around Putney Mountain are not always well-labelled, many run through private lands, and some of the many dirt roads devolve to Class 4 — not regularly maintained, generally not passable without all-wheel drive vehicles, and not plowed in winter. We drove where we could, then set out on foot.

Here B. stands next to the entrance of the first chamber, giving an approximate sense of the height of the mouth.

A side view of the same chamber. Note the stone wall climbing the hillside in the background.

What we called the terraced or “pyramid” structure around chamber 1:

The chamber features a drainage (?) channel cut into the rock. All of the chambers face roughly east, and this particular channel runs due east, judging by readings from B’s smart-phone compass app.

V-shaped entrance to chamber 2 — note what appears to be a stone “lintel” in the foreground.

B crouched within chamber 2 — larger than chamber 1, and quite dry inside. The massive roof plates of stone easily weigh several tons each.

Looking out from within chamber 2. Unlike the first chamber, this one was dry enough to sit on the earth floor.

Chamber 3 differs in the location of the entrance. Here is what looked and felt to both of us like a “processional walk” to the chamber. Merely a path left from frequent hikers exploring the area? Or something else? How to tell?

Continuing the approach to chamber 3.

B standing at the roof entrance to chamber 3 for a sense of scale. The beech (?) to the left appeared at least two hundred years old.

Close-up of the kiva-like entrance to chamber 3. The interior is deep enough for a person to stand upright in the oval space, about 8 feet (2.4 m) across.

Chamber 4 — the roof has fallen in on the far side. Stone taken for building elsewhere? Similar design to the others — but perhaps run-off from hillside weakened the roof.

Despite both learned and amateur speculation, no convincing conclusions about the purpose of these chambers exists. Colonial smokehouses? Storage sheds? Native ritual or burial chambers? Nothing quite seems to explain the massive construction, cramped and damp spaces, the exceptions of the details of chambers 2 and 3, etc. Similar stoneworks around New England raise similar questions. While dating suggests pre-European construction in some locations, other sites present what appears to be intermingled periods of building/repair.

/|\ /|\ /|\

One of the often ironic tests of a spiritual path is that it doesn’t comfortably “turn off” just because we may want it to. Many have “left” Christianity or another religion, only to find it still tugs at them, especially at vulnerable moments when our hearts stand unguarded, or broken open by events most of us face in simply living. A death, a love lost, a talent explored and trampled, a friendship severed, a dream deferred too long. The heart’s desire. J. K. Rowlings’ Mirror of Erised — desire, reflected back to us.

This is high on most lists of inconvenient human truths: a god or gods don’t release me from commitments I’ve made, just because I tire of them; the discipline I began that over time has shaped my awareness, habits, and life choices isn’t something I can smoothly abandon at whim, or even in the face of deep and ongoing challenges; the realm “outside the box” that I poured time and energy into doesn’t vanish just because bugs and snakes start to creep in from across the border.

If a path “has heart” (to use words from that curious 60’s classic series, which author Carlos Castaneda gave to his Yaqui teacher Don Juan), that heart beats with or without me, and asserts its own claims regardless of my feelings about the matter. (Of course, if the path doesn’t have heart, I’m riding a long con, and have an equivalent set of painful lessons to learn.)

And yet. To look deeply and honestly into this matter, I need to set these next words of Castaneda side by side with what I’ve said above:

Anything is one of a million paths. Therefore you must always keep in mind that a path is only a path; if you feel you should not follow it, you must not stay with it under any conditions. To have such clarity you must lead a disciplined life. Only then will you know that any path is only a path and there is no affront, to oneself or to others, in dropping it if that is what your heart tells you to do. But your decision to keep on the path or to leave it must be free of fear or ambition. I warn you. Look at every path closely and deliberately. Try it as many times as you think necessary.

For me there is only the traveling on paths that have heart, on any path that may have heart, and the only worthwhile challenge is to traverse its full length — and there I travel looking, looking breathlessly (The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge).

And in the best style of answering one quotation with another, here is Gildor Inglorion counseling Frodo in the The Fellowship of the Ring. To set the scene for those not versed in the “secular scripture” that is Tolkien, Frodo is leaving the Shire with Sam, and has encountered dark intimations of the path he has set himself to walk:

Gildor was silent for a moment. ‘I do not like this news,’ he said at last. ‘That Gandalf should be late, does not bode well. But it is said: Do not meddle in the affairs of Wizards, for they are subtle and quick to anger. The choice is yours: to go or wait.’

‘And it is also said,’ answered Frodo: ‘Go not to the Elves for counsel, for they will say both no and yes.’

‘Is it indeed?’ laughed Gildor. ‘Elves seldom give unguarded advice, for advice is a dangerous gift, even from the wise to the wise, and all courses may run ill. But what would you? You have not told me all concerning yourself; and how then shall I choose better than you? But if you demand advice, I will for friendship’s sake give it.’

Well, what did I expect? A one-sided and definitive answer will never spur me to use my own understanding, or kick me out of the spiritual immaturity where I’ve been lounging, waiting for someone else to make my big decisions. Even if another “knows all concerning myself”, how then can that person choose better than I can? Don’t most of my troubles issue from allowing another to do just that? I’m not talking about childhood, but about assuming the mantle of adulthood which modern society conspires to discourage us from ever doing, if we can avoid it with the pretty toys it serves up to distract us.

Instead, wise counsel generally arrives in harmony with what we already know in our marrow, and may be resisting — it confirms what we suspected all along. “To have such clarity you must lead a disciplined life”, Don Juan notes. When I yearn deeply enough for what is my birthright, a way opens. Often that’s our first taste of a kind of discipline not much talked-about: the kind we earn by living, and suffering when necessary to clear the crap away. Clarity has arrived, usually at some cost. Nothing, finally, can keep it from me. “When the student is ready, the master appears”, goes the ancient proverb. That master may be partner, friend, the stray who takes up residence and opens my heart, the neighbor whose children cross into my yard, fall from my fruit trees, and teach me compassion for others. It may be a stubborn refusal to give up, give in, give out. Whatever guise you take, Mystery, may I know and welcome you again.

/|\ /|\ /|\

As the second tree of the Celtic ogham “tree alphabet”, the Rowan, ogham ᚂ and Old Irish luis, is associated with Ovates, the second of the three Druidic grades in much of modern Druidry.

Rowan, or Mountain Ash, is certainly up to that role, both physically and symbolically.

In Europe one common native variety is sorbus aucuparia; in the U.S. it’s usually sorbus americana. The rowan’s leaves resemble those of the ash, but the two trees belong to different families, the rowan being a relative of the rose. Standing out front of our southern Vermont house, “our” rowan was the first tree to alert me to the attention the previous owner, a native of Austria, devoted to certain plantings on the land. Not hard to notice, when our rowan stands near the road, offering its protection. In fact, roadsides are a common location for the rowan, often planted by bird droppings containing the seeds. Its European species name aucuparia means “bird-catcher” — the rowan attracts birds like cedar waxwings — we often see a flock of them come through in late winter, and strip any remaining berries for their sugars and vitamin C.

(A little digging uncovers research demonstrating the rowan’s central importance for humans as well, particularly in Austrian folk medicine, as an anti-inflammatory and treatment for respiratory disorders, as well as “fever, infections, colds, flu, rheumatism and gout” according to the article at the link.)

The sky was overcast a few minutes ago when I took this picture. The red-orange berries are still ripening, and will be ready for harvest in October or early November, after a frost. Though our tree bears the brunt of winter’s north winds and a spray of snow and sand at each pass of the snowplow in winter, it’s a tough, scrappy species and still flourishes. Wikipedia notes:

Fruit and foliage of S. aucuparia have been used by humans in the creation of dishes and beverages, as a folk medicine, and as fodder for livestock. Its tough and flexible wood has traditionally been used for woodworking. It is planted to fortify soil in mountain regions or as an ornamental tree.

The rowan’s Old English name is cwic-beam, “quick” or “living” tree, which has survived into modern English as the variant name quickbeam. The name of one of Tolkien’s Ents in Lord of the Rings, Quickbeam is “hasty”; his Elvish name Bregalad translates to roughly the same thing — “quick” or “living” tree.

As a tree sacred to Brighid, the rowan also produces five-petalled flowers and fruit with tiny pentagrams opposite the stem — barely visible in some of the berries below, especially at the bottom left:

What put the tree before my attention now in particular is an invitation to serve in the Ovate initiations at East Coast Gathering in a few weeks. A rowan stave with a ᚂ on it will make a good gift to each of the new initiates.

The rowan shrugs off cold weather — it can be found at remarkably high altitudes; it flowers in white blossoms in spring and produces red berries in autumn. Thus it earns its nickname “delight to the eye” in the 7th century Irish Auraicept na n-Éces. As a tree to represent the toughness, persistence, and changing work in each season required to pursue the spiritual journey we’re all on, the rowan is a worthy candidate. It is often named the “most magical” of all the trees. As protection against another’s enchantment, it can aid us in creating our own.

Its mythological and folkloric associations are many. (You can find another rich link on the rowan here.) As a “portal tree” facilitating entry and return from other-worlds, the rowan invites contemplation under its branches.

/|\ /|\ /|\

Image: berries — Wikipedia rowan.

In New England the Sturgeon Moon, as some Native Americans call it, arrives this coming Sunday, the 26th of August, but early enough in the morning that many will observe it the previous evening.

Rowan in the front yard, its berries ripening

OBOD Druids are encouraged to do monthly Peace Meditations on the full moon. I never have, which is odd, considering how largely the moon figured in my teens and twenties. For years I observed its phases and influence, absorbed what I could find about its significance in diverse cultures, wrote poems and songs to it, connected to Goddess through it. But a peace meditation?

You could say I absorbed the wrong things from Christianity: “Think not that I am come to bring peace on earth: I came not to bring peace, but a sword” (Matt 10:34). This has proved one of the most accurate of Christian prophecies. Though it’s not so much a prophecy as a statement that this is a world of the flow of many energies. By its very nature, changes keep coming, and the shifts and rebalances can’t all be smooth, given the pockets and reservoirs of other energies that may resist or simply move on a different time-scale and energy flow.

Druids are called to be peacemakers, and the popular Peace Prayer stands ready as a worthwhile practice, daily for some. Here’s one version of the words:

The Peace Prayer

Deep within the still centre of my being

May I find peace.

Silently within the quiet of the Grove

May I share peace.

Gently (or powerfully) within the greater circle of humankind

May I radiate peace.

Find, share, radiate: all are valid practices I see as part of my own practice. Spiderwebs and hurricanes co-exist in this world. Both will manifest long after I’m gone and forgotten, but I can choose how I will align myself each day. I prefer, actually, to focus on love, which can exist even in tumult and turbulence, when peace has long fled. A home with children and pets and one or more working adults may not know much peace, but it can still overflow with love. A damaged landscape after the rebalancing that storms bring needs love more than peace.

/|\ /|\ /|\

OBOD ritual proclaims, “Let us begin by giving peace to the quarters, for without peace can no work be”. I don’t know what kind of work you do, but if I required peace before I started, I’d get nothing done. Don’t get me wrong: I value OBOD ritual, much of the language engages me, helping in the work of magic, but there I must turn aside and let the moment flow past. So I give love to the quarters instead, something they seem to use more readily.

A fragment of a prayer that has stayed with me — maybe someone can identify its source — I encountered decades ago, though I’ve never been able to track it to its lair. But I’ve remembered it fairly accurately, and I’ve recited it often: “I drink at your well. I honor your gods. I bring an undefended heart to our meeting-place”. This triad of actions faces outward in a way I know I can practice myself. For me it establishes a distinct vibration I value.

It also points toward a way I can hear and answer the call to serve.

“Serving is different from helping”, writes Rachel Naomi Remen. I cite her words in full below, because the following text has become so important to me, as a meditation seed and guide and source of wisdom.

In recent years the question how can I help? has become meaningful to many people. But perhaps there is a deeper question we might consider. Perhaps the real question is not how can I help? but how can I serve?

Serving is different from helping. Helping is based on inequality; it is not a relationship between equals. When you help you use your own strength to help those of lesser strength. If I’m attentive to what’s going on inside of me when I’m helping, I find that I’m always helping someone who’s not as strong as I am, who is needier than I am. People feel this inequality. When we help we may inadvertently take away from people more than we could ever give them; we may diminish their self-esteem, their sense of worth, integrity and wholeness. When I help I am very aware of my own strength. But we don’t serve with our strength, we serve with ourselves. We draw from all of our experiences. Our limitations serve, our wounds serve, even our darkness can serve. The wholeness in us serves the wholeness in others and the wholeness in life. The wholeness in you is the same as the wholeness in me. Service is a relationship between equals.

Helping incurs debt. When you help someone they owe you one. But serving, like healing, is mutual. There is no debt. I am as served as the person I am serving. When I help I have a feeling of satisfaction. When I serve I have a feeling of gratitude. These are very different things.

Serving is also different from fixing. When I fix a person I perceive them as broken, and their brokenness requires me to act. When I fix I do not see the wholeness in the other person or trust the integrity of the life in them. When I serve I see and trust that wholeness. It is what I am responding to and collaborating with.

There is distance between ourselves and whatever or whomever we are fixing. Fixing is a form of judgment. All judgment creates distance, a disconnection, an experience of difference. In fixing there is an inequality of expertise that can easily become a moral distance. We cannot serve at a distance. We can only serve that to which we are profoundly connected, that which we are willing to touch … We serve life not because it is broken but because it is holy.

/|\ /|\ /|\

I’ve mentioned before on this blog that I practice two distinct spiritual paths. One of the teachings on the other path concerns waking dreams. “A waking dream is something that happens in the outer, everyday life that has spiritual significance”, writes one of my guides on that path. And the crucial point, for me, is that I can perceive that significance. Or miss it. Or call it coincidence, or something else.

In her post “The Reality of Omens“, Druid Life blogger and author Nimue Brown writes,

When looking for omens in the world around us, it is necessary to consider how reality works in the first place. One of the things I have rejected outright is that other autonomous beings could show up in my life as messages from spirit – because the idea that a hare, a sparrowhawk, or some other attention grabbing thing could have its day messed about purely to try and give me a sign, is profoundly uncomfortable to me. I have something of an animist outlook, and I do not think the universe is *that* into me.

Brown’s caveat rings true — we can safely pare the human ego down, without fear it will crumble and disappear. Unlike the average toddler, most adults handle reasonably well the discovery that they’re not actually the center of universe.

But as a fellow semi-animist, I’d not separate “spirit” from what you and I and other things are doing every day. “Spirit” isn’t a thing that stands apart from what it inhabits — it’s not a bearded Jehovah lounging in the heavens, lording it over the rest of the cosmos, twitching the puppet-strings to get his way with us. Spirit permeates things — it’s what peeks out when you look in the eyes of a dog or bird or bug, or into the heart of a flower. It’s what gives waves their curl, or cumulus clouds their cotton-like billow, or your jogging neighbor the will to keep at her four-mile routine, in spite of December sleet. Spirit makes things thing-ly — how else can I detect its presence? Ever seen it hanging out all by itself? Pay attention and I can notice now more, now less. But never apart from the things it’s been doing all along, like you and me and the grass growing tall in the back lawn where I haven’t mowed it at all this year.

The skies cloud over, the temperature drops and a wind kicks up. Is it an “omen”? No — but these things do carry meaning to anyone paying attention. It’s probably going to rain soon. That particular kind of omen we call a “no-brainer” (though humans still manage daily to ignore even obvious omens). As part of the universe where a local storm is brewing, I can pick up on other things spirit is doing, or I can ignore them. The universe “isn’t that into me”, but it is in fact *in* me, and in you too, and we’re both in it.

So I prefer to see “omens” and “signs” as friends visiting. Spirit is simply flowing. One of its flows is you, another is me, a third is the car pulling into the driveway with S. at the wheel, “just stopping by” on her way home after shopping. If I gain insight or wisdom or a nudge to do something, or a burst of gratitude from that visit, then I’m paying attention in some way, and I’m being me, with my own unique responses to what spirit’s always doing all around and in me.

Rather than worrying overmuch about whether it was a sign or an omen or simply another wave in the ocean of spirit manifesting everywhere and everything, why not measure its effects? Is my life deeper, richer? Are the lives of others made richer and deeper? Is that enough, without checking the box labeled “omen” or “not omen”?

But what of the autonomy Brown names as part of her animist understanding of the uni-verse, the “one-turning”?

The idea that “other autonomous beings could show up in my life as messages from spirit – because the idea that a hare, a sparrowhawk, or some other attention grabbing thing could have its day messed about purely to try and give me a sign, is profoundly uncomfortable to me”, she notes.

But she and the many other beings in her life can be and are many things at once. And so are you and I. Like spirit in us and all around, I am many things at once. I am not “purely” anything, but delightfully mongrel. I’m an incarnate human, and also a Vermonter, a husband, a blogger, an aging white male, a person alive in the 21st century, an American, the son of two parents who both lost fathers while still in their single-digit years. I am a manifestation of spirit, a homeowner, a Druid, a teacher, a conlanger, a portal of Mystery, and so on. (Maybe the problem isn’t labels by themselves, but that we never use nearly enough of them. Scatter them like seed. Each is — not a limit — a possibility.) Each of these features opens access points for spirit to reach other beings, while leaving me with the same freedom as other “autonomous beings”. Spirit does “overlap” and “interconnection” really well.

My individuality and freedom are what spirit uses to connect with all other free and individual things. Spirit as the whole, the universe, seems to “love” individuals — that’s why there are many of us, rather than just two or three. Spirit as “one thing” interconnects and links all things, all these other “one things”.

So when a crow flies overhead while I’m checking the squashes in the garden, the crow is a crow and a friend visiting and a reminder, if I’m listening, of animal intelligence and and and. Its appearance and my awareness meet, for whatever comes from that meeting. Omen, sign, friend visiting, reminder of crow wisdom to fly over things before I decide to land on them, spirit guide — because spirit is always sparking the beings it pervades — to eat, fight, flee, love, mate, birth young, flower, fruit, grow old, die, return, become, become.

And the crow also discovers and learns something. Here’s a human that does not aim a gun at me as I fly over. Here is a water supply, a pond I can drink from. Here are trees to roost in, good cawing branches to talk to the rest of the flock, food sources to peck at in the scraps and compostables that get put out almost daily. And a hundred other crow things I don’t know about, without shapeshifting to Crow, or crow to me.

Brown goes on to make a key observation about our attention:

I can however read something into my behaviour at this point. I was in the right place at the right time, and I think that tells me something about my relationship with the flow. I take exciting nature encounters as good omens not because I think nature is bringing me a special message, but because it means I was in just the right place, at exactly the right time, looking the right way and paying attention. That in turn means I am in tune, and would seem to bode well for anything else I’m doing.

I simply take “encounter” as “message”. Humans are meaning-makers — it’s what we do. Any omen is an amen, an awen, a chance, a doorway. Will I walk through it? Or will I see how spirit walks through it — to me and to everyone and everything else? And as these things happen, can I catch the Song that is always singing, just at the borders of hearing?

/|\ /|\ /|\

Article in today’s New York Times: “What does it mean to be human?” touches on some of these matters.

A SPIRITUAL TOOL

When I first started blogging here in October 2011, I simply knew I wanted to think out loud about the turns in my journey. Begin the journal or blogging habit and, depending on its focus, it can turn at length into a marvelous spiritual tool. Journey, journal — there’s good reason the two words are linked in several European languages.

What you’re reading now marks my 500th post. To paraphrase Lao Tzu with a simple but slippery truism, a blog of 500 posts begins with a single word.

Philip Carr-Gomm, Chosen Chief of OBOD, writes about blogging:

Just as the spiritual path can be characterised as the ongoing attempt to both remember yourself and forget yourself, so blogging can be seen as a challenge to both be more personal, more open, more sharing of the riches of a life and at the same time to take yourself less seriously, to let go of the concern about what other people might think about you, and to reveal rather than conceal your curiosity and amazement at the often crazy world you find yourself in.

YOUR SUPPORT

I’ve also appreciated your support over the years, readers. Who knew that a blog that explores sometimes obscure philosophical issues, includes book reviews and article critiques — also sometimes on obscure topics — and recounts spiritual experiences issuing from the cauldron blend of two quite different minority spiritual paths could eventually draw, if WordPress stats can be trusted, an average of 35 readers per day from over 142 countries?

A DRUID WAY “Top 20”

Here are the posts you’ve voted with your pageviews as the all-time Top 20 — since inception.

Shinto – Way of the Gods — actually a group of posts on Shinto, beginning in 2012. A Japanese life-way that sustains much Druidic energy. Imagine North America or Europe with a comparable practice and ancient tradition …

Fake Druidry and Ogreld — this one struck a nerve in 2013, and occasioned a few sequels since then about an imagined “One Genuine Real Live Druidry”. Several readers missed the intermittently satirical tone and the point that “what works” is what matters, not lineage, however old.

A Portable Altar, a Handful of Stones — a 2012 post which discusses how an altar “gives a structure to space, and orients the practitioner, the worshipper, the participant (and any observers) to objects, symbols and energies. It’s a spiritual signpost, a landmark for identifying and entering sacred space. It accomplishes this without words, simply by existing”.

About Initiation, Part 1 — the first of two posts from 2011 on this perennially popular topic.

Grail and Cross—Druid and Christian Theme 5 — one of the most popular posts from a 2017 series.

Beltane 2015 and Touching the Sacred — a post about a major spring/summer festival and its imagery — why wouldn’t it be popular?

A Review of J M Greer’s The Gnostic Celtic Church — published in 2015, while Greer was still active Archdruid of AODA. The text reflects some of the fascinating blends of Druidry and Christianity that have been manifesting.

East Coast Gathering 2012 — the first of my reviews of ECG, now in its 9th year.

MAGUS 2017: The Mid-Atlantic Gathering U.S. — a burst of Beltane energy from the third of the major U.S. Gatherings after ECG and GCG (Gulf Coast Gathering).

The Four Powers: Know, Dare, Will, Keep Silent–Part 1 — one of a 2013 series.

The Four Powers: Know, Dare, Will, Keep Silent–Part 2 — the second of a 2013 series on the Four Powers behind magic.

Opening the Gates: A Review of McCarthy’s Magic of the North Gate — a 2013 review of British magician Josephine McCarthy’s book, written in part based on her experiences in the U.S.

Magpie Religion — the only post from all of 2014 to make it into the Top 20. Read it and ponder why, as I still do.

Romuva – Baltic Paganism — a 2016 post on a remarkable European Pagan movement.

Inward to Ovate — This 2015 post detailing my move from the Bardic to Ovate Grade in OBOD, in addition to a respectable number of views, has also earned the curious distinction of attracting by far the most spam of any post on the blog. The secret must lie in certain keywords in the text that spambots love to pursue …

The Fires of May, Green Dragons, and Talking Peas — a 2012 post about Beltane that pulls in allusions and references from spirituality and literature.

Fighting Daily Black Magic — a 2015 post on the greatest practitioners and targets of black magic — we ourselves, against ourselves.

Keys to Druidry in Story — the second of two posts from 2011, about the origins of some of the most widely-used training materials in contemporary Druidry.

Earth Mysteries – 1 of 7 – The Law of Wholeness — a 2012 series reviewing Greer’s book, in which he reworked the seven cosmic principles of the 1912 Kybalion into a text on ecological spirituality.

About Initiation, Part 3 — another in the 2012 series on a potent subject.

And a BOOK

Here’s to another 500 posts! And to a book, now in reasonable draft form, that draws on themes and topics from the blog and that will be seeking a publisher in 2019.

/|\ /|\ /|\

“Who’s been here before you?”

Josephine McCarthy, whose Magic of the North Gate I reviewed here, writes about magic with the instinctive feel as well as insight of someone who practices it.

Among the many ways to conceive magic, she suggests one useful way is as an

interface of the land and divinity; it is the power of the elements around you, the power of the Sun and Moon, the air that you breathe and the language of the unseen beings … living alongside you. With all that in mind, how valid is it to then try and interface with this power by using a foreign language, foreign deities, and directional powers that have no relevance to the actual land upon which you live? The systems [of magic] will work, and sometimes very powerfully, but how does it affect the land and ourselves? I’m not saying that to use these systems is wrong; I use them in various ways myself. But I think it is important to be very mindful of where and what you are, and to build on that foundation (Josephine McCarthy, Magical Knowledge Book 1: Foundations, pgs. 19-20) .

Lest all this seem confusing (and it can be), recall again the prayer that reflexively acknowledges “… these human limitations … these forms and prayers”. The great challenge of spiritual-but-not-religious is precisely this — to find a worthy form. Find the forms that work for you, respect them and your interactions with them, and listen also for nudges and hints (the shoves you won’t need to listen for — that’s the point of a shove) to change, modify, adapt, expand, and try something new. A spiritual practice, like the human that applies it, will change or die. Sometimes, like the shell the hermit crab uses for shelter and carries around with it for a time, we need to leave a home because we’ve outgrown it — no shame to the shell, or to the person abandoning that form of shelter.

Besides, this sort of debate — about which deities and wights to work with, which elemental and directional associations remain valid and which have shifted, and so forth — while perhaps more acute for those inhabiting former colonies of European powers because of cultural inheritances and influences — resolves itself fairly quickly in practice. It’s best treated, in my experience, individually, and case by case, rather than in any dogmatic way applicable for everyone. Stay alert, practice respect and common sense, and work with what comes.

What does this have to do with Brighid?

I’ve written of intimations I’ve received from one who’s apparently a central European deity, Thecu Stormbringer. The second time I visited Serpent Mound in Ohio, I heard in meditation a name I’ve been working with: cheh-gwahn-hah. Deity, ancestor, land wight? Don’t know yet. Does this name or being somehow remove or downgrade Brighid from my practice, because it has the stronger and more local claim, emerging from the continent where I live? Could it in the future? Certainly it’s possible. But in my experience, while other beings assert their wishes and claims, it’s up to us to choose how we respond. We, too, are beings with choice and freedom. That’s much of our value to each other and to gods and goddesses. We have the stories from the major religions of great leaders answering a call. Sometimes they also went into retreat, wilderness, seclusion, etc. to catalyze just such an experience. All these means are still available for us.

For me, then, part of the Enchantment of Brighid is openness to possibility. The goddess “specializes” in healing, poetry and smithcraft — arts and skills of change, transformation and receptivity to powerful energies to fuel those changes and transformations. We seek inspiration and know sometimes it runs at high tide and sometimes low. As this month moves forward, we have a moon waxing to full, an aid from the planets and the elements to kindle enchantments, transformations, shifts in awareness.

/|\ /|\ /|\

“Yet such is oft the course of deeds that move the wheels of the world: small hands do them because they must, while the eyes of the great are elsewhere”. Elrond, Lord of the Rings.

One still-unidentified man stood up to a column of tanks in Tian-an-men Square after the Chinese army suppressed the protests there in 1989, nearly 30 years ago. The iconic photos spread world-wide.

Rosa Parks refused to yield her seat — in the colored seating section on a bus — to a white man, after the white section was full.

These and many other individuals may have caught the public eye and achieved a fame they never sought. It can easy to misunderstand in our media-obsessed age: we don’t have to win a golden hoard of likes on Facebook, or post the tweet that shakes the twitter-verse, for our lives and choices and actions to matter.

We may expect and wait and complain and despair, while the supposed “great” do nothing, even as all around us — and including us and ours — small hands and feet and voices and wills do what they must. And each of us does these things in our own ways every day, until “just one more” reaches and passes the tipping point.

Those who tell us there’s “no point” in individual recycling efforts, for example, because one person can’t shift a planet’s indifference, forget that in fact that’s how we reach the crucial tipping points of change. Like birds practicing migration, one and then a few and then a flock and then multiple flocks do short practice runs, till the whole group is ready, when they weren’t before. The small wings — hands — voices — deeds are in fact the most common way we launch changes, for both worse and better.

What’s on your loom? What pattern are your deeds weaving?

If we’re prudent with our energies, we practice “starfish moves” (link to well-known short story). If we value each individual — as most of us say we do — then “starfish moves” are the only way most of us will effect change. We focus on one and one and one. Leaders take their cues from others as much as anyone does. And if they don’t, they’re not forever. “When I despair”, said Gandhi, “I remember that all through history the way of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants and murderers, and for a time, they can seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall. Think of it — always.”

I see the Rowan’s berries slowly ripen to red in the August sun. The previous European-born owner of our land planted the tree squarely in the front lawn, a proper tree of protection, but also of beauty, as it puts forth leaves and white blossoms in spring, then red fruit in autumn.

Second of the Ogham trees, luis, bright tree sacred to Brighid, the Rowan’s fiery nature is a good prod to Ovates like me, who need to bring light and fire on the journey through the dark of the inward paths they often walk.

Rowan, Rekindler, you face me each day I look out the front window, reminding me the depths of the Ovate way are not to be mastered like some sort of ego project to crow about, as if I can walk and gather and know them all, but respected as teachers. Always more remains to learn, to discover. You recall me to the need for humility before the unknown, coupled with boldness to do the necessary seeking.

I am an individual, yes — that’s how spirit manifests, the only way spirit manifests, in my experience. Rowan, human, leaf, seed, bee, birch. But a corollary: the universe also expends individuals ruthlessly, with appalling profligacy, every moment. A billion tadpoles each spring, and only a few reach full froggy adulthood. A thousand seeds from each blackberry, and only a few root and leaf and carry on the next year. The individual is a means, not an end.

I can respect my individuality most by treasuring the same manifestation of spirit in others wherever I encounter it, humans, trees, gods, bugs, snakes. And I do that by being an individual, respecting my own potentials and limits, just as I value the capacities and boundaries of others. Neither less nor more, false meekness nor arrogance, answers what we are each called to be and do. I need not apologize for swatting this mosquito landing on my neck — my blood is mine, and I defend it quite properly — but neither do I need scorched-earth tactics to rid the earth of every last biting and sucking insect, which would fail in any case — or doom me with them.

“I celebrate myself,” says Whitman, “and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you”.

And as I’d also put it, tweaking and enlarging Whitman, one of our original Enlargers already, so he shouldn’t mind, “what you assume I shall also assume, for we both participate in this universe, this ‘one-turning’, together”. We rub far more than just elbows, living as we do cheek-by-jowl on this spinning earth.

“There was never”, says Whitman, “any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now”.

What then? A reason to despair? No, to my mind, anyway. We do not add to or subtract from hell or heaven, but move through them, manifesting them moment to moment by our choices and our small or large deeds. How will I move the world’s wheels next, in my own small and large ways? How will you? What have I learned so far?

/|\ /|\ /|\

Photo courtesy Srinivas Ananda.

Granderson, Benjamin and James Granderson. Falling in the Flowers: A Year in the Lives of American Druids. Amazon, 2017. Kindle Edition.

Stone Circle at Four Quarters Sanctuary — photo courtesy Anna Oakflower

The Granderson brothers, a photojournalist and ethnographer team, key their book to the general reader, taking care to provide a short introduction to Paganism and some of the main strands of contemporary Druidry. But given their focus on a particular OBOD Grove, Oak and Eagle (hereafter abbreviated OAE), and largely on the two leaders of the grove, David North and Nicole Franklin, the text has a valuable immediacy often lacking from such studies. The 97 color photos also go far to bringing the reader into an experience of living Druidry, and grounding it in vivid sensory detail. (Respecting copyright, I include other images here to enliven the text of this review.)

The Grandersons are also careful not to generalize too far from their experience embedded with a specific Grove. Benjamin writes:

Unlike my previous project on Paganism, this work is a tighter focus; one which examines a very select group of Pagans who follow a specific Druid school of thought: The Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids, or OBOD for short. Starting with Dave and Nicole, my brother and I investigated the lives and practices of these individuals who called themselves OBOD Druids (pg. 10).

In addition to taking care not to paint all Druids or even all OBOD members with the same brush, the authors nevertheless back up assertions like the following with specific examples, detailed description and photos.

Since the OAE is more intensive than a typical Seed Group, the core members are very tight-knit and comfortable with one another, and often consider the others to be close friends and confidants. From woodland camps to the living rooms of suburban houses, there is a clear culture of openness, where one moment raucous drinking and jokes are interspersed with moments of deep discussion and potent ritual (pg. 23).

One comes away with the impression of the significant trust the OAE members placed in the Grandersons, and the authors don’t betray this trust in intimate portraits of OAE members and their practice of one form of 21st century Druidry.

David North, second from left. Photo courtesy Gail Nyoka.

Catching David at a point near the completion of his Ovate studies, and the transition of OAE from Seed Group to Grove, Granderson perceptively observes,

While what constitutes “completion” of the course material varies from person to person based on the correspondence between them and their mentors, before all else, a person’s evolution through the grade work determines if they feel like they have achieved balance (pg. 35).

Much of the non-hierarchical and non-dogmatic character of OBOD comes across in comments like these, in large part one of the signal accomplishments of OBOD’s current leader, Philip Carr-Gomm.

The authors also show themselves sensitive to picking up on Druid cultural practices:

(a) widespread hugging in greeting and farewell, often even among those meeting for the first time;

(b) the relaxed quality of “Pagan” or “Druid Standard Time”, in which events happen in a fluid and intuitive way, not on a strict schedule, but more when the group as a whole feels ready, and almost everyone alert to group energies feels a subtle shift toward action;

(c) unspoken taboos against bad-mouthing other Druid groups (in part because people are often members of more than one, each affording a unique set of teachings and perspectives), and

(d) a kind of ritual respect, so that during unscripted moments in ritual, when attendees are invited to toast, offer thanks, blessings, prayer requests, etc., one forgoes invoking a deity or energy out of keeping with the group, or exclusive to one’s personal practice.

Part of the authors’ experience drew them in deeply enough that the boundaries between observer and participant start to blur. Undesirable as this continues to be in good ethnography, it confers the authority of personal witness to what the Grandersons can recount:

I situated myself on the floor, text in hand, and I began reading. The text started off like the beginning of the Imbolc ritual, with the calling to the corners and the centering of the self. While I read the text aloud, Dave moved from corner to corner of the room, gazing into the expanse—at what I did not know. The text then changed, and from that point onwards I began to lose any understanding, only picking up something about ancestors. I was intent upon trying to guess when to stop to give Dave time to perform the ritual, while also fighting my excitement about getting a good photo (pg. 81).

Something of the eclecticism present in OBOD practice emerges. While much of the study material is Celtic in origin or spirit, OBOD members come from such varied and often mixed backgrounds that the OBOD ethos encourages members

to throw away selectivity and investigate and study the wisdom and traditions of all their ancestors, spanning time and geography, to form a complete profile that honors all of those that came before … to be open toward other traditions and practices that do not belong to one’s ancestral background, and to be willing to recognize wisdom and truth no matter what source it comes from (pg. 89).

Recording the mood, participants, ritual actions and aftermath of several of the Great Eight seasonal festivals of Druidry and Paganism generally, the Grandersons caught the generally relaxed ritual mindset, as well as the personalities of individuals:

There were some slip-ups, with a ritual participant or two walking the wrong way at first, starting a line too late, or failing to light a candle due to a stubborn lighter. An occasional glance would be cast at Dave or Nicole, seeming to seek their validation. Dave looked on stoically, though always welcoming and patient; he knew from experience these rituals were never flawless (pg. 109).

Though much of modern Druidry is indeed visible, or at least detectable with some modest effort at inquiry, if one is interested, there is a quality of what might be termed “spiritual privacy” to even its public rituals. This is a cherished skill among the Druids I know, one for intermittent discussion, certainly, and always a matter of judgment and discretion. Each person assesses the line he or she prefers to observe in how public the individual practice of Druidry should be. The Grandersons capture it well:

OAE wasn’t afraid to be out in public, but they made that public space private. They didn’t hang a sign up saying, “Druid Meeting Here,” or make announcements on a loudspeaker. They also chose a pavilion that, by design and location, created seclusion; it was a reserved piece of land that they sanctified, and they created an island for themselves for a day. Again, this speaks to the contemporary Druid’s ability to take what is modern—a state park pavilion—and make it ancient, carry out their practices in the open air, and somehow remain largely hidden (pg. 124).

The authors divide their book in to poetically captioned sections: Introduction; What is A Druid?; Opening the Door; Naked Before the Full Moon; Into Spring; Beltane; Branching Out; Trip to Four Quarters; The Latter-Half of the Year; Living with Dave and Nicole (a ritually full time, with a wedding of Druid Hex Nottingham and his wife Daisy, East Coast Gathering, a baby-naming ceremony during the same Gathering weekend, a local Pagan Pride Day, etc.); A Detour to New York (with an interview with another Druid, Nadia Chauvet); and The End of the Journey.

cabin banners at East Coast Gathering

This review has focused more on the first half of the book; the second half builds on it, with more interviews of members we have already encountered, and observations specific to their experiences.

MAGUS Beltane fire-circle. Photo Courtesy Wendy Rose Scheers.

In sum, I recommend this book to the “Druid-curious” for its detailed reporting and photography, and for conveying, as close as text and photos can, something of the experience of what doing Druidry actually feels like. And to those familiar with Druidry who may also know many of the Druids it portrays and interviews, it’s a pleasure to read and ponder. Finally, as an insight into the energy, organization and personalities behind the very successful MAGUS gatherings of 2017 and 2018, it also deserves exploration by anyone interested in contemporary Druidry and in organizing focused and effective Pagan events.

/|\ /|\ /|\

What is it about our insecurities, that headlines like this draw readers? Partly it’s just clickbait, of course: we read out of pure curiosity or boredom or distraction. “What fresh hell is this?”, critic and author Dorothy Parker supposedly exclaimed, every time her doorbell rang. But partly and too often, we ARE insecure. Taught to trust authorities over our guts, or to ignore our guts altogether, we get taken for a ride, conned, hustled out of our own good instincts.

Doing Druidry Right (DDR) Principle 1: Always take into account what the gut has to say.

Are there ways to do almost anything wrong? Sure. That’s not news, however, and the universe usually lets us know first of all, before anyone else has the slightest inkling. If you’re not sure, there’s always Facebook, where you can post and invite potential mockery on a worldwide scale never before available. A piece of unsolicited advice in the form of a question: who really needs to know absolutely everything you’re thinking and doing and feeling right away, before even you have taken time to reflect on it, at least twice, if not a good Druidic three times? Practice only that much of wisdom, and a good half of our current hysteria would die off like flies after the first hard frost.

Now that research confirms the the “second brain” of the nervous system surrounding the gut [link to Scientific American], the old proverb gains new life. “Gut is second brain, and sometimes better”.

DDR Principle 2: Unless death is imminent, I have, and should take, the time to pause and reflect on whatever I’m thinking, doing and feeling — and more than once. Only then, and only perhaps, should I speak — or post about it. “Dare not to overshare”.

“The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad”, says Thoreau, “and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior. What demon possessed me that I behaved so well?”

The opposite, of course, holds true just as often: “The greater part of what others think is bad …” In these days of extremes, I no longer always take this as literary exaggeration but good counsel. If I carry suspicions around like nutcrackers, I often find the meat of an issue still untouched in much debate and controversy and shouting.

DDR Principle 3: Keep asking, like the rallying cry to the soul that it is, that old Latin tag: where is wisdom to be found? Ubi sapientia invenitur?

When you know your answer truly, you’re usually halfway to an answer for others, too. Then it may be time to share. Not because you know, but because you know your way to knowing. And your way (not The Way), is a useful guide to encourage similar trust and perseverance in others as they manifest more of who they are becoming.

/|\ /|\ /|\

“Congratulations, you’re doing Druidry right”.

That’s much more useful and salutary feedback. Ignore for now — unless they’re life threatening — any glitches along the way, and focus on growth. Build a store of successes, a reservoir of energy, and then tackle the inevitable pests and parasites that have accumulated around your growth.

The Well of Segais, Vermont’s new OBOD seed group (a first step to forming a Grove), met to celebrate Lunasa yesterday at Mt. Ascutney State Park on a rainy and gorgeous day.

Seek out even semi-wild places in off-weathers and you’ll often share the space with non-human inhabitants. We had this pavilion “to ourselves” for ritual and after-feast. The mountain presences greeted and participated with us.

And what a dreamlike scene across the valley — the view from the pavilion of impossibly rich shades of green, and mist-cloaked mountains.

Five of us gathered to celebrate this first of the the three harvest festivals, with a lovely ritual and a feast of the season.

“It is the hour of recall. As the fire dies down, let it be relit in our hearts. May our memories hold what the eye and ear have gained”, says the close of the OBOD ritual.

And so they do.

/|\ /|\ /|\

“What makes a Druid a Druid?”, asked a recent post to a Druid Facebook group I follow. The question, and the responses that followed, are both wonderfully instructive. I’ve distilled a large number of comments into thirteen ways of addressing the question. Below are the condensed originals, along with my indented comments.

1) A sickle, a white robe and a beard. What else?

This is one popular image, which we can trace to the Roman historian Pliny (link to short excerpt from his Natural History). Though it ignores the reality of female Druids in both the past and present, it does show that rather than a set of beliefs, Druidry suggests a set of tools that one uses in roles that Druids fulfill. In this case, harvesting the sacred mistletoe from the oak.

Ellen Evert Hopman likes to point out that white is really impractical — it shows dirt. Some of the oldest surviving Irish Druid materials talk about certain colours and patterns of cloth set aside for Druids — but not white. Wearing white stems partly from the influence of Pliny and partly from practices of the Druid Revival of the 1700s and onward.

2) A desire to seek knowledge regardless of belief or faith, a desire to keep that knowledge safe and a desire to share that knowledge with those able to understand it.

A good first draft of a Triad: “Three desires of the Druid: to seek knowledge, to preserve it, and to share it with others”. But many of us linger in desire without ever bringing it into manifestation. Desire alone won’t make a Druid.

3) Knowing when to put the kettle on.

Though it’s another piece of humour, timing of course matters deeply, and the “trick” of “catching the moment” reveals a great deal. Alertness to the hints the world is constantly giving us can guide our days. Likewise, obliviousness to such nudges and intuitions simply means our lives will be that much harder and less joyful. Nature so often is our first teacher.

The 21st century and most of its challenges reflect how often we’ve missed catching the moment and willfully ignored the many hints coming our way. Now we’re simply going to learn the hard way for the next few centuries. Neither Apocalypse nor Singularity, damnation or salvation: but a good deal more schooling in what we didn’t bother to learn the first few times round.

4) Initiation.

As a one-word answer, “initiation” points us in an important direction. But what we think it is, where and how we seek it, and what we do with it once we “have” it — those are places we can trip up.

As one commenter noted, “a Druid isn’t a ‘what’ – it’s not a thing to be initiated into. A Druid is what you are – you can be initiated into Druidry, but that doesn’t make you a Druid”.

Though, as another commenter observes, “self-initiation is a thing”, we are never alone: spirit, spirits, the ancestors, animal presences all participate in both “self” and group initiations.

In a larger sense, too, “initiation” happens to everyone. Life itself initiates us, through love, suffering, birth, death, the seasons. In that sense, we’re all “Druids in training”. Some opt to work with such energies more consciously and deliberately.

The Morrigan personifies the challenges that prove and test us all. Photo courtesy Wanda Flaherty.

5) Membership in an Order.

For many — and it can be a valuable step — what “makes a Druid” is membership in an Order. The path of the Solitary means doing preliminary training on one’s own, and the requisite patience and listening and discipline of the Solitary aren’t for everyone as a starting point. Solitary work can feel trackless at times — how do I know where to focus? How do I assess my efforts? An Order can lay out for us its set of answers to such questions. However, to do more than merely “belong” or “be a member” — to grow into Druidry — still requires that same patience and listening and discipline which the Solitary practices.

6) Doing the necessary work.

As a commenter says, “Whether as a solitary or as a member of an order, WORK is required. Otherwise, to call oneself a Druid is meaningless”.

7) Study, reverence, work in nature, and commitment.

For most Druids I know, one or more of these may flag at times. It’s unavoidable. Jobs, relationships, changing health and life circumstances all demand much of us. Returning again and again to pick up the work is what “makes a Druid”.

“Persistence …” says one of the Wise. “Is not this our greatest practice?”

8) Alternative answer: you have to be able to summon a unicorn or a dragon. You can also grow a tree that grows/attracts its own dryad.

Again, though a bit of humour, these answers point to Druidry as something people do rather than something they merely believe.

9) Living in honourable relationship with nature, the Gods and the tribe. (And the evidence that we’re doing this?) The ability to model and teach all of that.

10) There is a special badge you get that says “I’m a Druid” on it …

Ask a silly question …

If you’ve been at some Druid or Pagan events, you may on occasion have wondered whether it’s the bling that makes the Druid. Fortunately, no.

Theme for meditation: what says “I’m a Druid” to the non-human world around us?

11) Practice, experience, and listening.

Another good Triad to take into meditation. Each of the three informs and feeds the other two. What am I listening to? Is it nourishing the deepest part of me? If not … What have I learned from experience? How can that shape my practice? Does either practice or experience show me new things to listen for? What is teaching and guiding me today, right now? What is my next step?

12) 19 years of study … at least for the ancient Druids.

As others have pointed out, the dozen or more years of modern education most of us undertake account for a chunk of those 19 years, but by no means fulfill or equal all of them. A Druid who persists on the path finds in the end that those symbolic 19 years cover just the “introductory material” anyway …

13) You are a Druid when your community says you are — fulfilling the role.

This presents a paradox of sorts. It means I practice and work on fulfilling the role, though recognition may or may not come right away — or ever. But that’s not why I’m practicing. I’m not a Druid until I possess that inherent authority of experience that others recognize, yet I won’t possess that authority or experience unless I practice despite all lack of recognition. My indifference to such recognition as I practice is often a more sure way than any other to attain it.

One advantage of membership in an Order is that the community of members will come to recognize this authority. People will begin to turn to a wise and compassionate Bard, even though others who’ve completed the “higher” grades may also be present.

Another commenter reflects: “Because being a Druid is defined by function, it’s not something you can be in isolation. You can train as a teacher, and maybe even qualify. You can call yourself a teacher. But you are not in reality a teacher until you have taught someone, just as you are only a healer if you have healed someone. You are only a Druid if you carry out the role of a Druid”.

/|\ /|\ /|\

With a hill to our east, we greet the sun itself about an hour after astronomical sunrise, and as I begin this post, it’s growing in strength as it clears the trees, doubly welcome after overcast days and fogs and thunderstorms. Hail, Lugh, in all your guises!

At Mystic River Grove‘s Lunasa celebration on Friday, I had to laugh: we were blessing with fire and water as part of the ritual, and a light rain had just begun to fall through late afternoon sun. No need — fire and water are already with us, my inner Bard satirist exclaimed. Sometimes you just want to celebrate what is — sometimes ritual gets in the way, if Things already are chorusing all around you. But we doggedly went ahead anyway. Couldn’t we just recognize what was already with us and dance in the rain around the fire in welcome?! No need to invoke the Directions, either, snorted my inner Bard, irony-meter on high. Where do you think you are? North, south, west, east — they always embrace you. You stand at the Center, always. No distance.

Nothing like a gathering of Druids to kick my awareness of change and focus. Discomfort can be a useful guide for where to look, a shift from the stasis we too easily fall into day to day.

This morning I woke early and read a little.

Consider a cup of coffee. The energy needed to run the coffee maker is only a tiny portion of the total petroleum-based energy and materials that go into the process. Unless the coffee is organically grown, chemical fertilizers and pesticides derived from oil are used to produce the beans; diesel-driven farm machinery harvests them; trucks, ships, and trains powered by one petroleum product or another move them around the world from producer to middleman to consumer, stopping at various fossil-fuel-heated or -cooled storage facilities and fossil-fuel-powered factories en route; consumers in the industrial world drive to brightly lit and comfortably climate-controlled supermarkets on asphalt roads to bring back plastic-lined containers of round coffee to their homes. To drink coffee by the cup, we use oil by the barrel.*